Words by Lula Criado

Dr Immy Smith is a polymath – an artist, scientist, and data analyst who explores human and scientific narratives using both art and science.

In her last project, Connecting Brain Tumour Narratives, a 10-month residency at Portsmouth Brain Tumour Research Centre (PBTRC) she explores ‘the human narratives of brain tumour research’ through conversations with brain tumour patients, friends, family members and scientists.

Scientific research is about understanding the invisible through the microscope. Investigating, studying and learning the molecular, genetic and cellular behaviour allows scientists to find the why, where and how any kind of modification that leads to developing a disease or tumour happens.

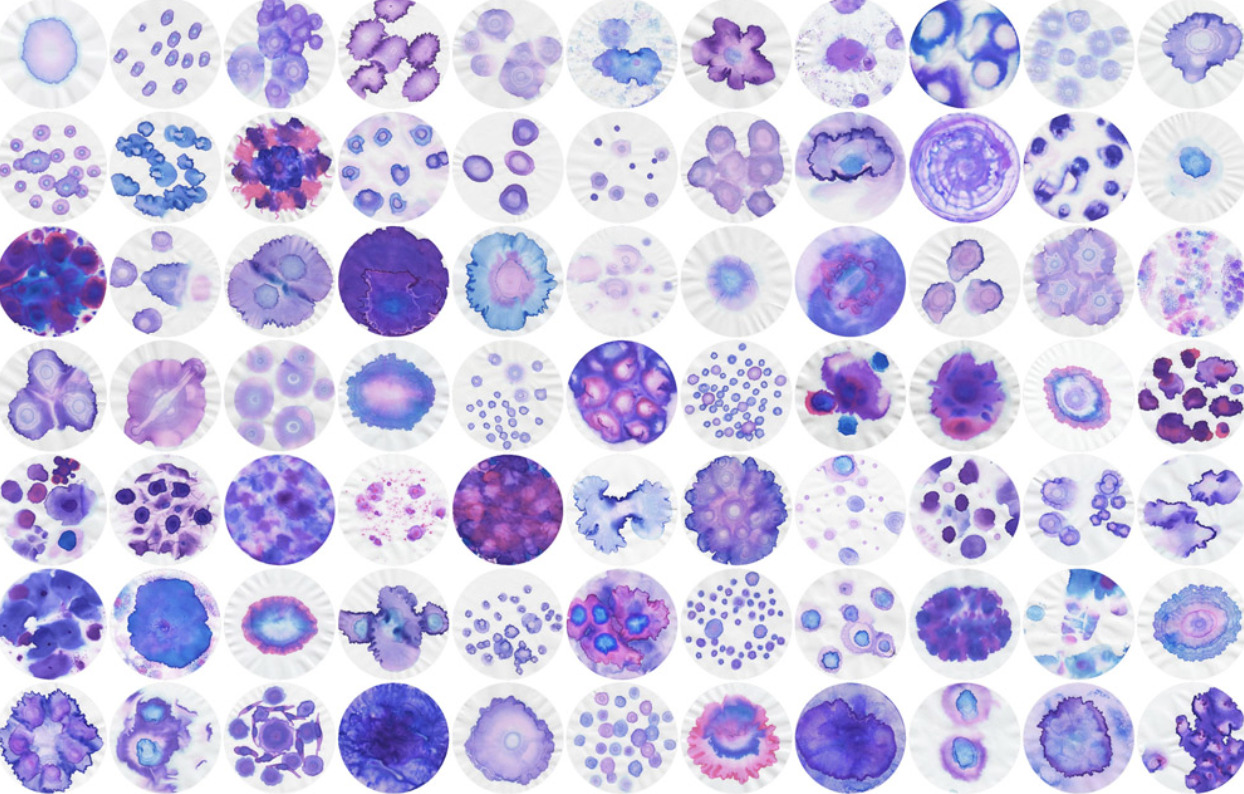

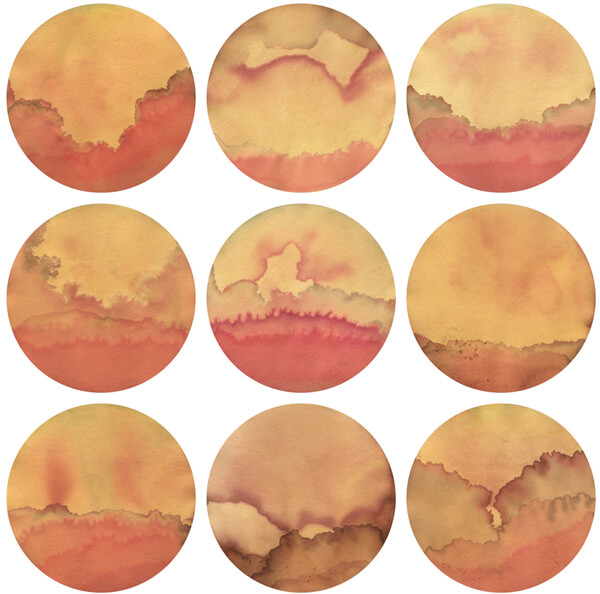

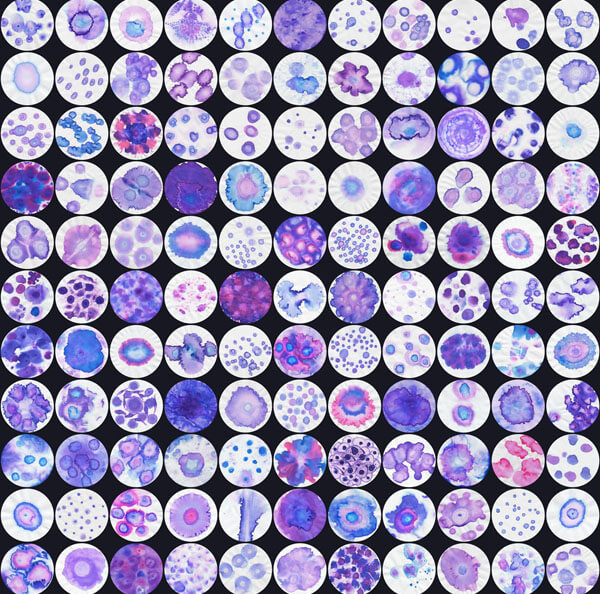

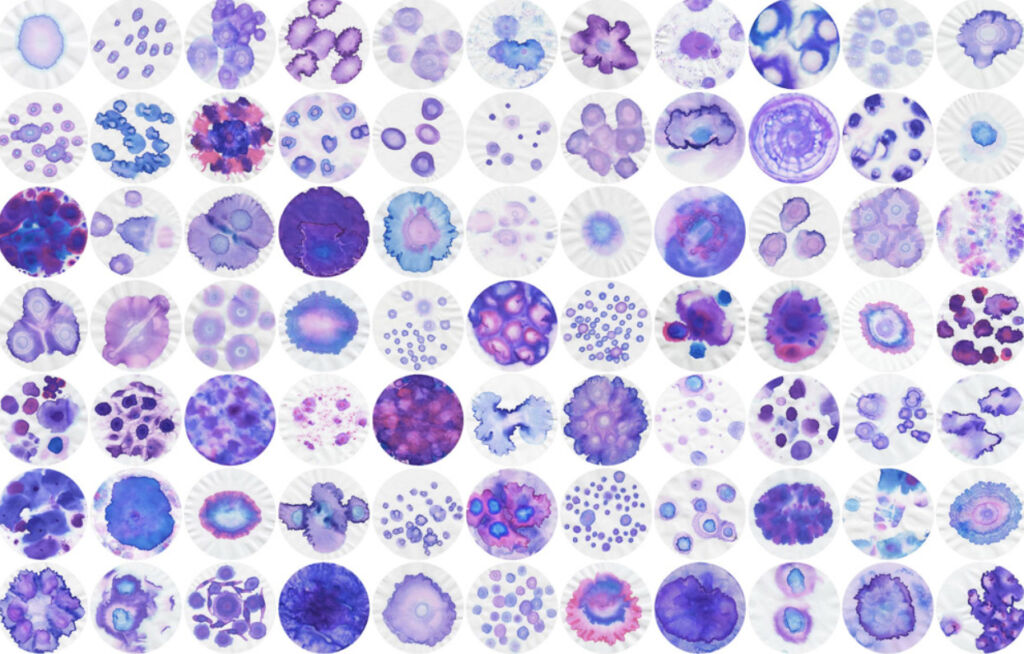

However; in the hands of polymath Immy Smith, brain tumours are seen from a new approach more artistic. The result of her artist residency is large ink patterns that aim to investigate brain tumours from a macroscopic point of view. Through participative workshops, each pattern was associated with a game or exercise which allowed the investigation of each brain tumour and define a new way of interaction between patients and family members and scientists.

You are an artist working in the intersection of art and science, when and how did the fascination with biological systems come about?

When? I always had this biological fascination – because I was allowed to! When I was young I wasn’t told to keep out of the woods, and I wasn’t kept away from puddles, beetles and fungi. I was allowed to be dorky and have mud in my hair. I was encouraged to poke about under dead wood for frogs and worms if I wanted to.

My mamma raised me with art materials alongside a cheap microscope. Even in a single-parent low-income family, I never went without pens and books, because she prioritised education over pretty much anything. I’m not going to lie and say I never wished for cool toys instead… but I don’t regret what I had now I’m older!

My parents were very polymathic too. They ensured I always had art AND science to explore the world with. It seems strange to hear talk about the ‘intersection between art and science’ as if these fields were immiscible…

as if an interface had to be built between them at some point, like a bridge over a gorge or crevasse that you could look down into… I don’t believe such a crevasse is real. I can’t look into that gap between art and science – it doesn’t exist to me.

Why do I have this fascination for one thing or the other? Why wouldn’t I be a better question don’t you think? I never had art OR science squashed out of me, because my mamma would take on anyone who tried that nonsense, haha!

I am going to be that fierce for my sibling’s children in return. They’ve grown up asking me about fume cabinets, pseudocode, and neurons just as much as drawing ideas, surrealism, and dye-making. I bought them their first microscopes this Christmas.

In the early 1920s, Cubism helped physicist Niels Bohr to determine the quantum theory when he compared the behaviour of electrons with Cubist paintings. But, in your view what is the contribution of science to the arts?

I think I am coloured by my own experience as an artist, scientist, and data analyst when you ask me that obviously, so it can be hard to step back from that and compartmentalise things. That is a flaw of being a polymath I suppose…

When I look at the way artists talk about their practice, and scientists talk about their methodologies, I think there is a lot of fruitful exchange that can happen there; learning scientific practice has greatly influenced my artistic methodologies.

But equally, I can say that there have been some scientific difficulties I would have found hard to overcome without the benefit of artistic means of inquiry… As a means to ask the same question in a different way, I believe the exchange between disciplines is very important.

It allowed me to have ideas I might not otherwise have, and when you mention cubism and Niels Bohr, this is an example of changing your way of thinking by interacting with another field of study, isn’t it? Biological textures, and the way nature solves problems with flexible forms rather than any particular aesthetic, which influence my artwork itself.

But I think it’s more important that art/science are allowed the freedom to influence each other’s ways of thinking and problem-solving, rather than any single facet of art/science being influential. Diffusion of thinking patterns may allow each field to become more flexible.

In Connecting Brain Tumour Narratives you explore/investigate brain tumours semiotically and connect with scientists, patients and their families. What is/was the biggest challenge you face in the development of the project? What ethical/philosophical issues arose during its development?

I had expected some issues with the ethics committee and approval process to enable us to work with patients – but actually, this went smoothly. It involved less paperwork than expected! We approached asking for the patient’s memories as if we were asking for a blood or tissue sample.

We treated the stories I collected with the same confidentiality, care, and rigour that is applied to biological material; just the method of collection and expected output were different to most research in the lab. I think the ethics committee and the project participants appreciated that.

I expected philosophical issues to perhaps crop up in relation to patient interviews – but patients all had a very strong sense of purpose in sharing their stories. I don’t know the best way to say this… They own their narratives, sometimes very fiercely, and want to use them against brain tumours and their devastating effects. Patients and family members want to be heard, and identified – everyone was offered anonymity, and no one took it.

Really, I am just a translator. I’m another means of disseminating their stories, and their urgency in trying to address the lack of funding and resources for brain tumour research. This is not a job for anyone with a big ego… I feel humbled by the strength of the people I have met, and proud to help them share their narratives. But they are not my stories. I just draw them.

Practical aspects were much more of an issue in this project. I ended up making very large ink patterns that aim to communicate the challenges scientists face, so we had space issues. At 1.5m square, these are the largest ink or dye pieces I have made. I feel it’s very important when working with scientists to be present; to be working alongside them so that there is a genuine exchange and understanding of each other’s work.

But aside from making the ‘Heterogeneity’ array out of smaller laboratory filters, the ink work was too big to be made in the lab. We overcame this by using a webcam in my studio, and a private Facebook group so that the scientists could still see me work.

Another huge practical issue was that I had a spine injury during the residency – I ended up having surgery actually. I desperately wanted to keep working on the project but was unable to sit properly, so the PhD students in the lab helped me construct a standing workspace in their office!

They even made space for me to lie down! I’m really grateful to them. They have a great problem-solving capacity that I will learn from.

What are your aims as an artist working in science and art?

My aim is to explore human and scientific narratives using both art and science. I will use all my artistic, scientific, and data analysis skills as required. To give you an example; every specimen in a herbarium provides information about a species of plant. It can provide DNA for analysis too. Combined with other specimens, it can provide environmental information, and tell you about the place where it grew.

It can provide botanical artists with a substrate to turn into an image of a living plant. BUT it can also provide an artist with the story of its human collector, the history from the time it was collected, and geopolitical information about where it came from.

Labels carry thumbprints, specimens arrive wrapped in local newspapers, and biological material acquires permits on its journey, and appears in collectors’ notes from the field. I’ve even found lichen samples wrapped in a child’s drawing from the 50s.

It was a drawing of a teddy bear in a toy shop with the price of the bear in old money on it. I have found letters from collectors to each other, tucked between pages on a herbarium shelf.

Histological specimens of human tissue have stories that travel with them too – if you know where and how to look. In the case of connecting narratives, we are connecting stories from patients and scientists by asking about objects, symbols, sounds, or smells, that are significant to them.

These narratives are part of the overall story of brain tumours. We will have a fuller picture of the human and scientific challenges of brain tumours by pooling skills and using all our faculties to investigate them.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

Asshats, and asshattery; both data and experience tell me that funding, galleries, art magazines, science conferences, academia, etc, still favour the male, white, and well-to-do. That really gets old after a while, it grinds you down…

I expect this pushes many people out of both art and science. Sometimes I’m surprised that I’m still here! Other than that, time is my big issue.

My brain is full of ideas and information and hardly have any time to express it. I’ve had chronic insomnia since I was in my teens, and sometimes I can use it to get extra time. But realistically, I’ve had to learn to be a good editor when it comes to what I could make versus what I can make.

It’s frustrating and I have to resist the urge to just give up because I can make so few things overall – that’s the real enemy. But as I get older I learn to manage my expectations of my practice better!

You couldn’t live without…

Oxygen. Water. Sugar. Friendship, cats, pencils, and caffeine. Wandering in the woods picking up twigs. Still poking about under dead wood for beetles and frogs… Oh, look! We’re back where I started! I do genuinely have mud in my hair today, too. Don’t grow up, it’s a trap.