Text by Lyndsey Walsh

Guy Ben-Ary, Nathan Thompson, and Sebastian Diecke form the transdisciplinary collaborative team behind the work Bricolage. Bricolage debuted on February 6, 2020, at the Fremantle Arts Centre in Western Australia and was produced by the Perth International Arts Festival in partnership with SymbioticA Centre of Excellence in Biological Arts at the University of Western Australia. The work is an amalgamation of years of research into the techniques and materials of past, present, and a potential future. This collaborative research effort has culminated in the production of living microscopic biological automatons made up of human heart muscle cells that have been embedded into silk structures. What was originally an ambitious undertaking, Bricolage has come to achieve a deep level of exploration into biological materiality that has yet to be seen in the field of Bio-Art.

While Berlin-based stem cell biologist Dr Sebastian Diecke served as the scientific collaborator for the work, Ben-Ary and Thompson are no strangers to working with stem cells in their own creative practices. Having previously collaborated with each other on the work cellF, which featured a neural net derived from induced pluripotent stem cells that could be stimulated by human musicians, Ben-Ary and Thompson are acutely aware of the difficulties and intricacies creating within the material world of stem cells. Coming together to work on Bricolage, Thompson and Ben-Ary decided to push the ideas of their ‘surrogate performer’ even further to create a series of alchemical transformations that have resulted in a self-assembling and twitching automaton as a form of a living kinetic sculpture.

Asserting itself as an act of ‘biological alchemy’, Bricolage instigates an investigation into the almost sorcery-like processes behind the metamorphosis of living materials. Starting originally with a drop of blood, Ben-Ary, Thompson, and Diecke worked through a series of transformations that enabled them to create their twitching heart muscle cells. Additionally, Bricolage’s ‘alchemy’ goes beyond the realm of stem cells and encompasses transformations of liquid silk into a jelly-like solid using novel light-printing techniques and clay that has been used to build the incubator housing and sustaining the life of these enigmatic and novel living entities.

Heart, silk, blood, and clay are all materials that have extensive histories in the broader cultural imaginary. While Bricolage reflects on these narratives in our collective past, the work also engages with the meaning of those narratives in our present and speculate on what they could mean for a future where we are reliant upon living materials in standard processes of production. For Ben-Ary, these layers of references and materials creates an interesting contrast in the work’s visuals and the ways the audience can interact with the work in the gallery.

What is truly unique about Bricolage is that the results of these alchemical transformations can be easily seen in real time. This achievement is something that has taken years of research, experimentation, and technological development for Ben-Ary, Thompson, and Diecke. While Ben-Ary and Thompson have developed a number of strategies during the creation of their work cellf, the process of bringing Bricolage to life in the gallery has had them confront new challenges when working with living materials.

Unlike the surrogate performers in cellf, which were entirely dependent on technology as the mediator to experience the ‘performance’, Bricolage pushes against the boundary between life and the machine. Thompson explains that in the process of making the work, they wanted to avoid the laboratory aesthetics that many Bio-Art pieces rely upon. Instead, Thompson explains that he wanted the final piece to be something audiences could easily interact with and there would be limited technological machinery used in the gallery. As a result, the living components of Bricolage needed to be grown large enough to escape the visual confinements of the technoscientific body.

The results of this pursuit are not only impressive for anyone who has worked artistically with living materials but also go beyond of what is known to be materially possible in the sciences. Ben-Ary and Thompson were able to grow their living automatons to structures that are roughly 7×7 millimetres in height and length. For a living structure grown outside of the body, 7×7 millimetres is a gigantic leap beyond what is usually seen in the laboratory. Thus, Bricolage has been able to achieve its visual independence from the microscope, projection, or any other technological mediation.

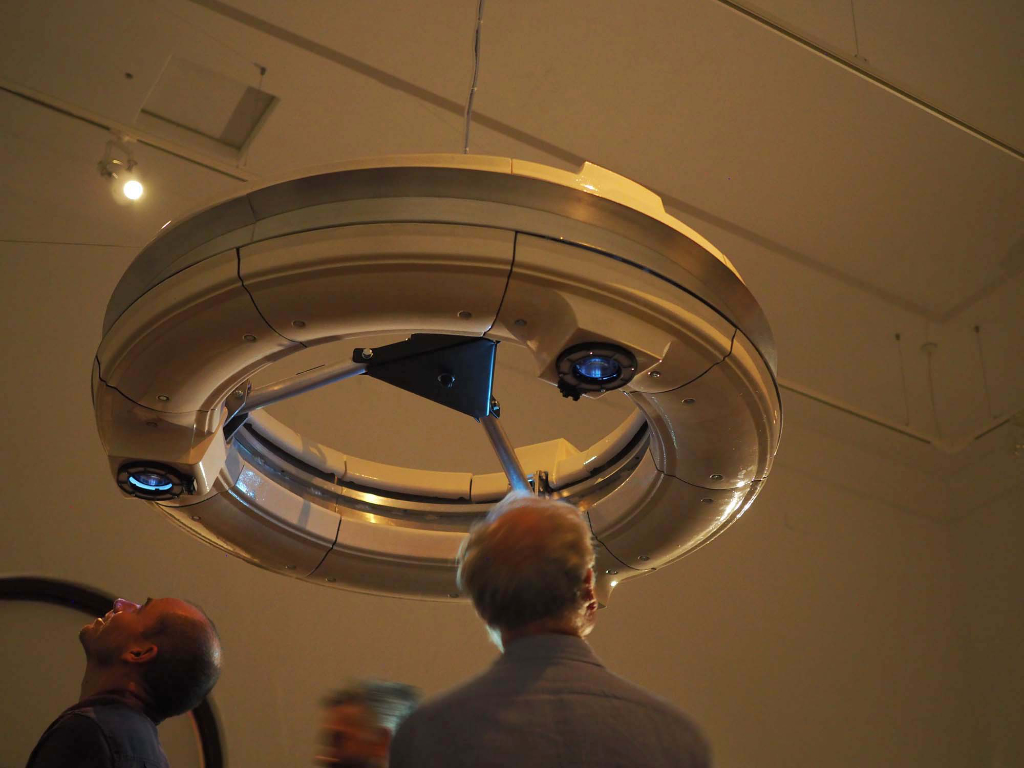

This has allowed for a whole new experience for the audience to have with a living and moving artwork. Instead of gazing down through a series of lenses, viewers peer up through the windows of the clay-built incubator to gander at the kinetic sculptures in action. Bricolage subverts normative visual relationships with laboratory-grown entities by switching the viewing position. The audience does not gaze subjectively upon them but instead strains to look up, thereby challenging the power dynamics between themselves and these otherworldly beings.

These living entities have also outperformed in other areas of the creative team’s expectations. Thompson has revealed that they were able to leave them in the gallery for over ten days before changing the liquid media that provides the cells with their essential nutrients for survival. This longevity in performance surprised both artists and scientists, and they observed that, in some cases, the living automatons began to twitch faster when left starved for longer periods of time.

Bricolage exemplifies a new class of artificial living entities with emerging behaviours that have been grown outside the body, and thus challenges current paradigms of ethical thought towards the cells and their treatment. As a whole, the work calls into question the role of the maker, the facilitator, and the enabler of lab-grown lifeforms. One of Ben-Ary’s hopes for the piece is that the audience can engage critically with the liveliness of the work in the gallery and begin to confront these disturbing questions surrounding processes of material transformations to create out-of-body lifeforms.

These disturbing questions are ones that many artworks coming out of SymbioticA and the biological arts tend to ask. Ben-Ary and Thompson’s particular focus on the transformative processes of creation at this intersection of science and art lead us also to raise questions about the means of production in our potential future. Sourcing can be a difficult process for many scientists working with living materials, but how far we can push existing resources of biological materials to create something new is question at the forefront of research in stem cell biology. When collaborating with Diecke, Ben-Ary and Thompson were able to share an open dialogue about these ethical questions that have propelled them to create the work.

So far audiences have responded to these disturbing questions on materiality with their own sets of ethical questions. Ben-Ary has described the strong feedback on the work as a result of the perceived liveliness of the piece. He explains that the questions the audience has asked back in response to work have ranged from “What the hell is happening here?” to “Can those artists do those things?” and “Who lets them do it?” Ben-Ary finds himself very supportive of this kind of feedback since he believes that it steers the audience into thinking more deeply about the ethics of creating and working with life in the laboratory and the ethics of a future where this will be a more common practice.

Ben-Ary and Thompson have big plans for Bricolage to continue to provoke audiences into ethical discussions, as they are now working on bringing it to new galleries outside of Australia.