Text by Sim Goodwin

We are sitting on the precipice of something. The world around us changes ever faster, but our future seems ever more confusing. In no context is this more apparent than in the mad world of politics, where we choose our future, our society, our ethics. Traditional politics as we know it is on the brink of collapse, giving way and whilst it may, for some, be a cause to rejoice, at the same time, what lies before us is completely unknown.

We must first look a little further to speculate on our immediate future. Only if we can imagine our destination can we know our path and what to expect along the way. Five years ago, before Trump, before Brexit, before the Extinction Rebellion, Me Too, and the Gilets Jaunes, designer duo Dunne & Raby imagined what the future could hold in a fictional, speculative design project – and now it has become more relevant than ever.

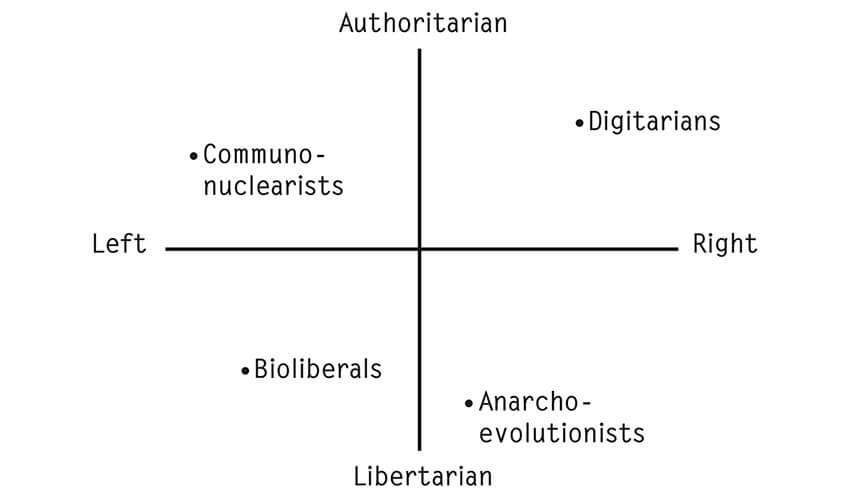

The project, United Micro Kingdoms (UMK) imagines a schism in British politics resulting in four superseding states within England, each ruled by a different faction – each with an allegiance to a different corner of the traditional Left-right, authoritarian-libertarian political spectrum. Four Kingdoms ruled in the manner of four speculative futures, four different political extremes.

Dunne & Raby are not just mere storytellers with overactive imaginations – research plays an incredibly valuable role in this project and across design fiction and speculation as a whole. The future can be planned out by extrapolating and analysing contemporary trends, emerging technology and historical events. In UMK, these futures are imagined with a specific emphasis on the idea of future transportation, how the population of each ‘nation’ will move, commute, and congregate.

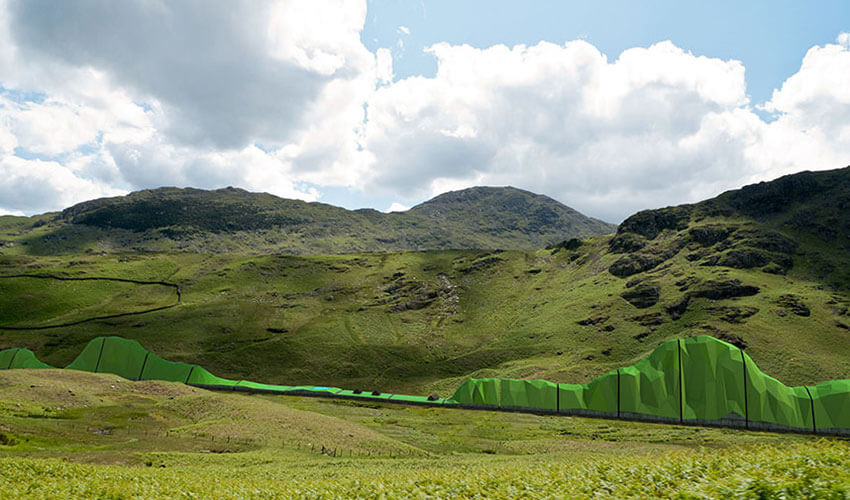

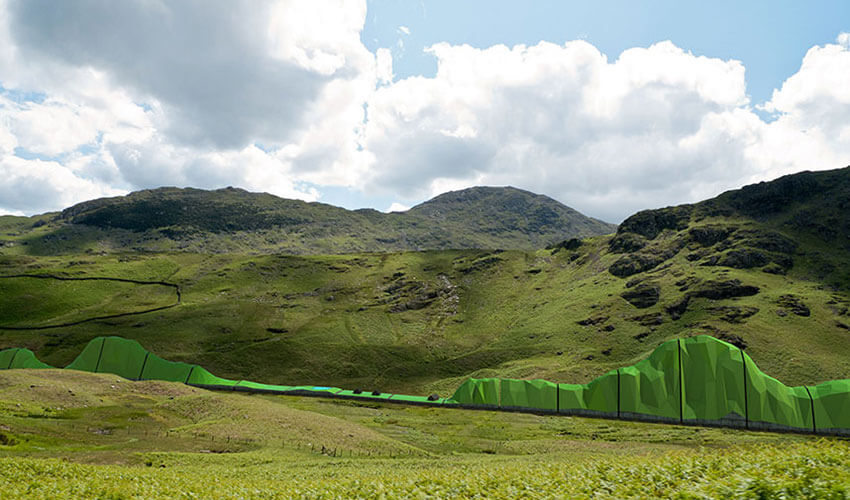

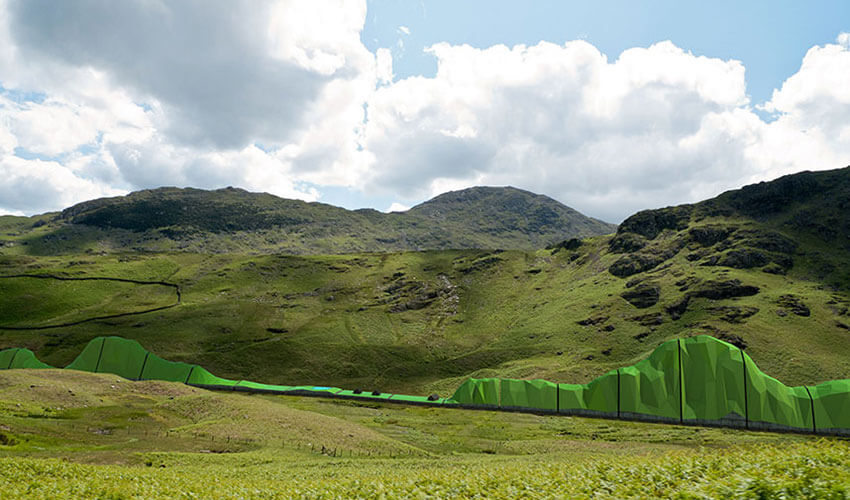

*There are the communo-nuclearists, who occupy the left-wing authoritarian space. Their lives are confined to residing on a giant nuclear-powered train of landscapes, carriages of artificial hills, valleys and plains. Living within these landscapes, the population are strictly regulated by a supreme government, yet retain all the amenities of modern life. Dunne & Raby describe them as ‘prisoners of luxury’ enjoying all the pleasures one could imagine but at the cost of personal liberty.

*The bio-liberals are progressive libertarians. A wild imagining of radical green politics, this retrograde nation sacrifices luxury, travelling using inflated skin gas bags powering slow, rickety and lumbering bio-cars. Through their complete re-evaluation of the car, new ways of existing are created using new values and ethics.

*Anarcho-evolutionists, are right-wing libertarians, whose respect for individual liberty is extreme. Effective bio-hackers, they engineer themselves and the world around them. In a nation without hierarchy, sociality and cooperation are important. Clans emerge around modes of transport – cyclists with artificially large thighs, tall & thin balloonists. Animals do not escape bio-hacking with hugely muscular horses used to pull heavy loads.

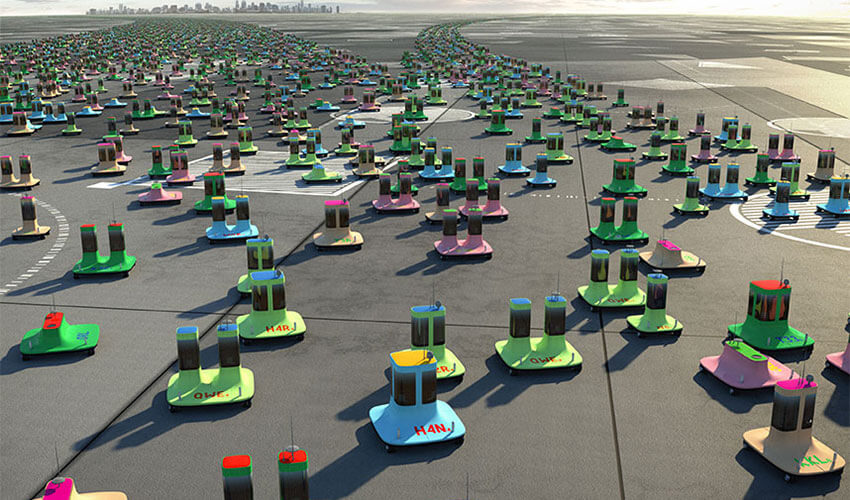

*The digitarians are conservative authoritarians, structured, market-led, ultra-capitalists, governed by algorithms. Nature is seen as a resource to be used and exploited. With the politics of growth, space becomes an expensive commodity. Throughout their kingdom, micro-sized self-driving digicars transport the population. Consumers pay tariffs to access the road network.

Already we can draw parallels between some of these imagined factions and current political ideals. The digitarians are the ones that we can relate to most – their system of pay-as-you-go access to the roads, 100% surveillance but 100% transparency and a near-sacred regard for the free market and corporations are really not far removed from reality in Western civilisation. Imagine a country run by Amazon Prime. A future like that is portrayed in Futurama. Whilst perhaps the most recognisable of these proposed systems, it is difficult to say that this is the most likely of the four outcomes – perhaps ten or twenty years ago it would seem reasonable to expect capitalism to be everlasting and self-sustaining, now discourse around this is changing, with more and more people agreeing that sustainable growth is an oxymoron.

Whilst most people will tend to agree that we don’t want to live in this digitarian future, the chances of us finding a consensus for an alternative is going to be slim. We all seem to agree with what we don’t like, but struggle to create a positive replacement for which there is a majority in agreement. Will it be this politics of withdrawal? Fearful wall building, cultures shying away from the world stage, people demanding unchallenged liberty in their own space and the expense of those who ‘don’t belong’.

There are definite parallels between the rise of right-wing populism and the anarcho-evolutionists. This could be the future of Trumpist politics. Anti-globalist, protecting local interests. Perhaps we should follow the advocation of the Extinction Rebellion. A complete re-working of the global economy – I think its quite safe to say this is the emergence of the bio-liberal kingdom, sitting at polar opposite to our current free-market capitalism. Can we stomach losing all our luxuries to live in such a world? Or are we destined to move into a communo-nuclearist future? Retain all those luxuries, live in a sort of paradise state, all at the expense of personal liberty?

There are no futures which seem ideal, no scenario which will appeal to a majority – that’s not the point. Instead, it’s through the imagining of plausible futures that we can discuss what we do and don’t like – but what will this discussion look like? One could easily argue that design fictions are little more than figments of the imagination, educated and decorated guesswork that is tarted up to the extreme with the objective of provocation. To what degree is this justifiable? In a field where friction is ever more apparent, arguments ever more vigorous and violent, what is the justification for stoking the flames with divisive, fictitious scenarios?

Dunne & Raby may succeed in creating discourse, but they are inevitably absent from curating the nature it. All good debates require moderation, and without it, UMK becomes a potentially dangerous project with the potential to broaden division rather than encourage unity. Such is the passion and energy of the political environment that even the most rational debate has the potential to distort and degrade into plain silliness and unrepresentative straw-man arguments. The validity of Design fiction in such a deeply complex and divisive arena could be questioned. After all, the introduction of fictitious futures, fictitious worlds, provides us only with something to argue against, a catalyst for dispute. Design fiction is cunning. It’s engineered. It’s fake news. It’s post-truth.

Yet, when we have so little idea about how our politics will change in the next year, let alone whether it will survive at all, speculative projects become invaluable for allowing us to weigh up potential futures, could-be scenarios from which we can learn. This is the value of speculative and fictional design in this context that we can, through future thinking, build up imaginary scenarios, whether utopian or dystopian and begin to understand what we want for future generations. If we have a target to aim for, then the only things we need to sort out are the stepping stones to reach it. Let’s hope we can be sensible in the debate.