Text by Ania Mokrzycka

It is with a certain feeling of urgency that I seek the nature, subject, words of the other story, the untold one, the life story, writes Ursula Le Guin in the The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction. Le Guin puts forward a story that defies linear progress and refrains from grand narratives and pompous heroes. Instead, it centers on lived experiences, personal encounters, and attunement, holding things in a particular, powerful relation to one another and to us. Cosmotechnics, the latest exhibition at FACT Liverpool, explores the intersection of nature and technology and brings seemingly heterogeneous “things” together to propose different modes of understanding and interaction with the (multiple) worlds.

Defying dichotomies, embracing interdisciplinarity and emergent approaches, Cosmotechnics engages and interweaves contemporary and ancient knowledge and processes, spirituality and science, natural and synthetic materials, 3D objects and video, fact and fiction, sleek production and lo-fi sci-fi aesthetics among other elements; all mobilised towards speculative rethinking of our more-than-human relations across different timescales.

Named after and inspired by Yuk Hui’s concept of cosmotechnics, the exhibition emphasises that technology’s true potential lies in its alignment with local cosmologies—spiritual, ecological, and cultural understandings of the world states curator Beatrice Zaidenberg. Zaidenberg describes her travels to Colombia as fundamental for deepening her perspective on how artists and communities hack, create and adapt technology to their own needs, abilities and surroundings. Technology is unpacked as a multiplicity of constantly evolving practices that can be driven by and utilised towards very different goals than those propagated by Western narratives of advancement. The idea of hacking is pertinent here; it frames the works in the exhibition as acts of disruption to dominant systems of knowledge production and meaning-making, reclaiming their existing infrastructures to channel ideas based on care and relational thinking.

Zaidenberg sought artists for whom technology is deeply embedded in the collective memory, spirituality and other belief systems. The collective of artists, biologists, and engineers Atractor Studio + Semantica was selected alongside two other artists – Patricia Domínguez and Rebeca Romero. Zaidenberg suggests the common thread between their works is the profound connection to plant life and their cosmologies. Plants are rendered as allies with their own agency and historicity, presented as active participants in building more sustainable and collaborative futures. They open up new dimensions and ways of sensing: the exhibition [encourages] a learning and relearning process as we move through different modes of thinking and interacting with the world around us, explains Zaidenberg.

Cosmotechnics unfolds across two spaces: Atractor Studio + Semantica’s works are located in the foyer gallery, while Patricia Domínguez and Rebeca Romero share an enclosed gallery space. Zaidenberg envisages each piece as a portal guiding the audience through the show. This idea evolved throughout the curatorial process, shifting from an architectural design where visitors physically pass through portals to something more abstract – portals defined by light, texture, and spatial relationships between the works she elaborates further.

Some works, such as Patricia Domínguez’s videos, Matrix Vegetal (2022) and Tres Lunas Más Abajo (2024), framed by geometric neons, embody the portal figure quite explicitly, taking audiences on a cosmotechnic, dream-like journey through tropical forests, quantum research sites at CERN, space observatories in Chile and ancient rock carvings in the Atacama Desert. Others, such as Rebeca Romero’s Codex I: Spring Equinox (2024) & Codex II: Winter Solstice (2024), which build upon pre-Columbian cosmologies and digital systems, remain more obscure; drawing the viewer in without offering the gratification of understanding. This notion of implicit knowledge, messages and histories to be sensed rather than grasped runs throughout the exhibition. Various cues and symbols point to connections within and between the works – it is up to the viewer how they meander through the show, discovering interrelated themes and forming new associations.

One aspect shared across Patricia Domínguez’s and Rebeca Romero’s practices is the recycling/remixing of materials, symbols and artefacts, often belonging to epochs distant in time. Rebeca Romero’s artefacts Caapi X (2024), Huachuma 3000 (2022) and Insignis SS (2024) were conceived as hybrids of psychoactive plants and pre-Columbian vessels (scanned from originals). Futuristic and ancient, a copy and an original simultaneously destabilise anthropocentric concepts of linearity and authorship. This is further amplified by the playfulness that characterises some of the works, especially in Patricia Domínguez’s rendering of technology and its interactions at the intersection of digital and analogue, scientific and spiritual.

Zaidenberg reflects that for her, playfulness is not just about lightness or fun; it’s a tool for engaging with speculative ideas, imagining new possibilities, and questioning dominant narratives. Through it, technology loses its masculinist associations with control and mastery, making space for experimentation, collaboration and enchantment.

While Domínguez and Romero created their pieces individually, they both present soundscapes that permeate one another in the gallery space. Sound ties the works together, creating new dialogues on a more subconscious level. “Sound becomes essential for guiding visitors. It engages other senses, drawing people into the scene in a way that visual cues alone might not. For me, it was important to create an environment that felt distinct from the outside world, a kind of sensory threshold that would draw people in, explains Zaidenberg. She returns to the idea of portals, thinking of how sound introduces a different realm, lulling the viewer into a space of quiet contemplation, allowing them to be fully immersed in the work. The sonic interventions made by both artists are subtle yet very present, creating a dense, almost palpable atmosphere. Still, individual sounds can be distinguished, cutting with clarity through the diffused softness of the intermingled soundscapes.

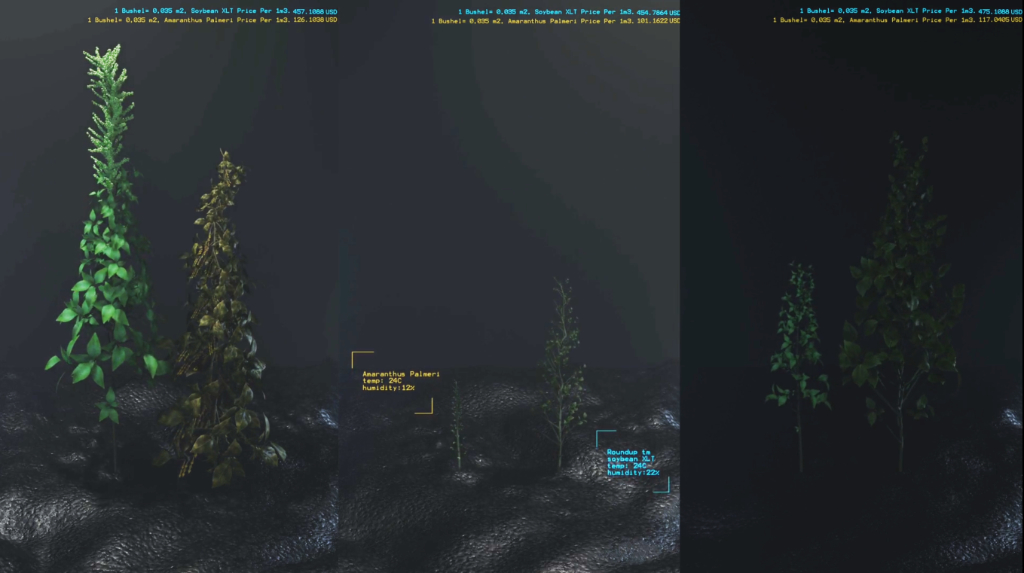

Atractor Studio + Semantica gives sound an even more prominent role: that of a witness. A Tale of Two Seeds (2023) is a subversive sound and video installation that interrogates new forms of colonial expansion and extraction in Latin America’s agro-industrial context. The collective employed microphones and ultrasonic detectors to create a soundscape that enables listeners to distinguish the difference in soil health between fields planted with soy (monocultures) and those cultivated with a diverse range of plants, such as amaranth (polycultures).

Deemed a parasitical weed in the west, amaranth, an ancient grain considered sacred for many Indigenous peoples, is brought back into focus through sound. Atractor Studio + Semantica invite the viewer to listen to what is often ignored or overlooked, whether that’s the subtle vibrations of a plant or the invisible forces shaping the environment, says Zaidenberg. This function of sound as a storytelling tool is employed across the whole exhibition, creating space for the works to communicate across different levels, from the visible to the invisible, the heard to the unheard.

Storytelling, in various shapes and forms, permeates Cosmotechnics through and through. Thinking about stories and world-making, Romero chose The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction as the text to read together with the participants of her Artefact Design & Worldbuilding Workshop (run as part of the exhibition programme). Like Le Guin’s story, full of beginnings without ends, initiations, losses, transformations and translations, and far more tricks than conflicts, far fewer triumphs than snares and delusions, Cosmotechnics brings about partial perspectives, shimmering visions and unfinished tales. Its propositions might sometimes remain cryptic or imperfect, but they harness hope for a world yet to be born, as emphasised in the description of Romero’s installation.

Reclaiming and returning to technology as a tool for resistance, resilience, and growth, the exhibition challenges existing power structures and conjures collective and self-empowering practices across various times, species, mediums, cultures and generations.