Words by CLOT Magazine

Joan Jonas, a veteran of the late 1960s downtown New York scene, is one of the most significant artists in video and performative art history. And next week, on the 31st of May, she will make a rare live appearance at Turbine Hall in Tate Modern, London.

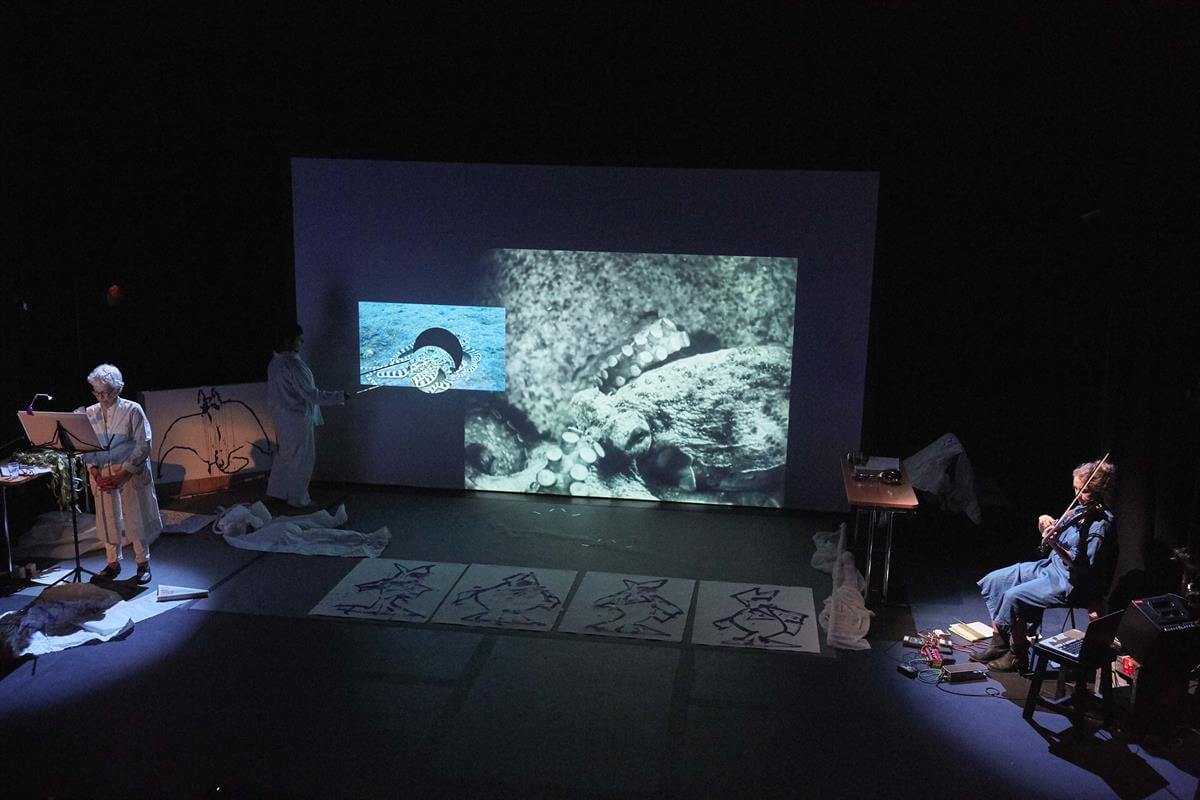

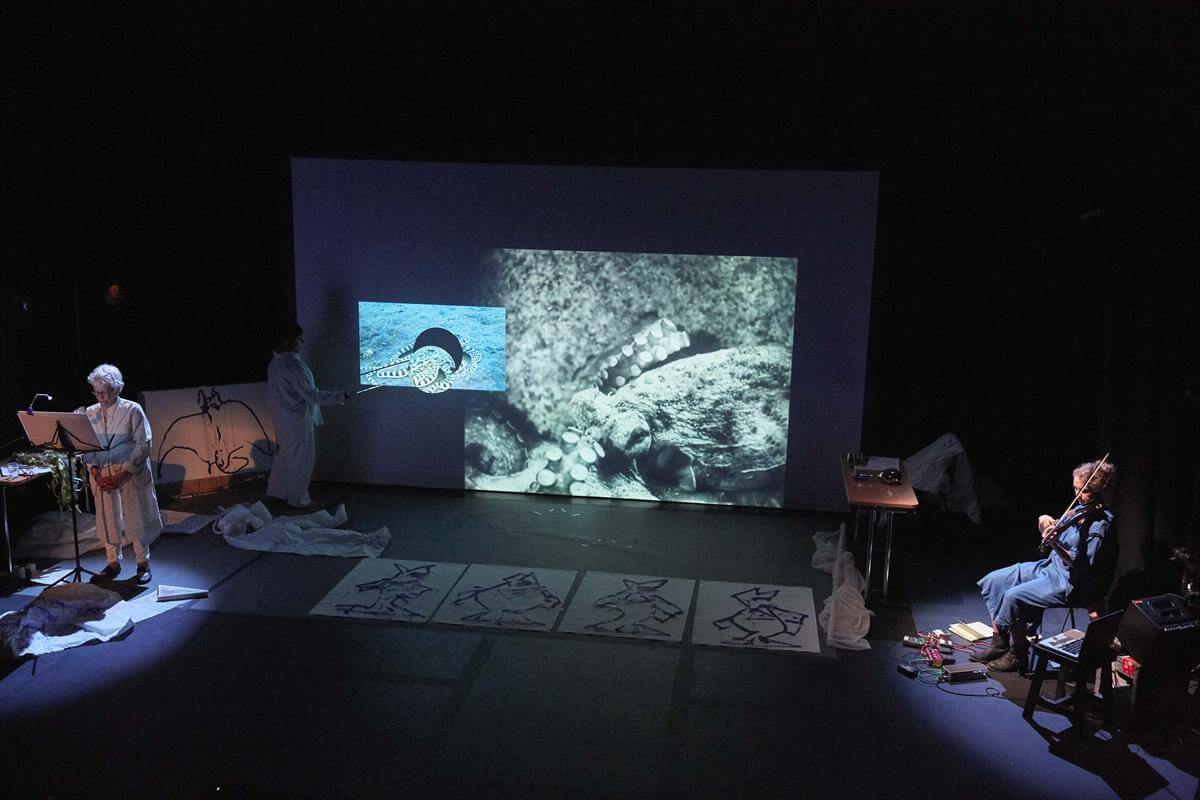

Commissioned by TBA21–Academy and presented in collaboration with Tate Modern, Joan Jonas will present the multimedia performance Moving Off the Land. Oceans—Sketches and Notes. The production pays tribute to the oceans and their creatures, biodiversity, and delicate ecology while celebrating the poetic, totemic, and natural entity as a life source and home to a universe of beings. Combining movement, live drawing, readings, and video projection, Moving Off the Land draws on literary and mythological references and Jonas’s collection of sketches and notes.

Oceans have been a recurrent thematic inspiration in Jonas’s recent works, whose work also has frequently engaged with ecological concerns throughout her career. In the late 1960s, as art opened itself to new practices and spaces, Jonas set her performance pieces—combining dance, theatre, live drawing, sculpture, and music—outside the museum, in lofts, studios, wastelands, beaches, or forests.

This performance is part of a more extensive program at Tate Modern showing Jonas’s pioneering work in performance, video, and installation, which includes a major exhibition in the level 2 galleries of the Blavatnik Building and the Tanks.

The main aim behind the show is to bring to a broader audience Jonas’ work as a pioneering figure. Her experimentation with a video camera (she was one of the first artists to include live video into her pieces) resonates very close in these times when images experienced through screens and cameras have become a very prominent way of how experiencing reality.

When asking the curators team what the intellectual process behind the exhibition was, they shared that “the layout was done in close collaboration with the artist. It is based on the concept of echoing and mirroring; elements of installations are re-appearing throughout the show, whether these are the masks that are on display in the first room and then occurring in some of the videos; or if it is propped that one can see in the documentation of early performances and then re-appearing in her later works; or if it is her concept of “stage sets” that she invented as a form for her sight specific words starting in 1976 and that she continued with the works Juniper Tree 1976, reconstructed 1994 and later Lines in the Sand 2002.

Finally, it is also Joan’s role as a designer of her works that led us curatorial: she invented her own media, such as the My New Theatre pieces and designed her own screens, which have a sculptural character as you can see in Stream or River, Flight or Pattern 2016-2017, in Double Lunar Rabbits 2010 or downstairs in the Tanks in Reanimation 2010/2012/2013”

One of the challenges of exhibiting new media, especially a retrospective, is keeping the flow and engagement of the experience. For this exhibition, ‘the greatest challenge was to make this experience of expansion also accessible for a visitor that is probably just there for one visit.

In the exhibition, we give an overview of early performances that have been restaged during the ten days of the Live Exhibition in March, we include Joan’s video Volcano Saga, a thirty-minute long video that is displayed as a single-channel projection which also exists in an installation version, and we show also selected performance documentation videos that accompany the installations in the galleries. In this way, we would like to ensure that the audience who missed the rich programme gets an experience of Joan’s practice as a whole”.

As a final reflection, when considering how Jonas’s work reflects on the current times where we find humans balancing between the imposed anxiety of both the post internet/post-information era and the Anthropocene, the curator’s team says Joan Jonas’s work often refers to fairy tales and myths.

Still, it is always also connected to the real world. It questions the role of women in myths; it challenges our perception of nature, and it makes us think about political and ecological problems. There is no moralising undertone; it is a rather poetic and humble way how she confronts us with these topics.