Interview by Belén Vera

Encountering Hicham Berrada’s work feels like stepping into a parallel world, where the familiar becomes elusive and perception is slightly distorted. Forms and elements seem recognisable, yet remain just out of reach, creating a disorienting tension between the organic and the artificial. Any attempt to decipher their logic, a wave of visual overstimulation takes over. His environments are immersive, alive, and in constant transformation, where scientific precision merges seamlessly with poetic abstraction, offering a rich visual experience.

Berrada’s artistic practice is deeply rooted in transformation, allowing natural forces and scientific principles to guide the evolution of his work. Rather than imposing form, he encourages a dialogue between control and chance, letting materials shape themselves. Through meticulous observation and experimentation, he reveals unseen dynamics, constructing landscapes that feel both organic and otherworldly.

By challenging the notion of permanence, his work highlights the transient nature of matter and the imprint of human intervention. Whether through real-time chemical reactions, biodegradable 3D sculptures, or digital simulations, Berrada embraces unpredictability, continually expanding the boundaries between art and science. As he prepares for new projects, including a real-time video simulation at Le Fresnoy, he continues to redefine the role of the artist as a creator as well as a catalyst for discovery.

The collaboration between art and science is essential in your practice. How did it all begin, and how would you describe the interaction between both fields in your creative process?

Two aspects of science as a culture have always fascinated me. Since I was a child, I’ve been drawn to the aesthetic dimension of science—things like botanical drawings, depictions of rocks, and other forms of discovery. This aesthetic interest extends to the visual language inspired by cinema, video games, and related fields. It’s a cultural and artistic fascination that has deeply influenced my perspective.

In my work, science functions more as a tool or a method to engage with matter, processes, and phenomena. Much of my practice revolves around creating spaces where things can emerge or happen. The parameters I set act as tools that allow phenomena to manifest or take form, often as images or processes.

My approach borrows from scientific behaviours or protocols, such as measuring, observing, and repeating experiments. For example, the act of measuring might seem routine to us, but when you reflect on it, it’s quite peculiar; we’re quantifying and engaging with the world in very structured ways. In my work, measuring, recording observations, and repeating processes serve a different purpose than they would in traditional science. They’re not about building empirical knowledge but about honing an intuitive understanding of matter and transformation. These practices help refine my intuition and make my exploration of materials and changes more precise.

What type of studies or research inspires you as a starting point for your projects?

I wouldn’t say there’s one specific type. At times, I’ve collaborated with scientists, often physicists, on different projects. However, as a starting point, my inspiration tends to come from images. I think more about old books with botanical drawings, illustrations of rocks, or works like those of Ernst Haeckel, with his intricate depictions of mitochondria and microscopic organisms. My inspiration is often visual—these images serve as a foundation for my ideas. Much of my work is driven by the goal of creating something inherently visual. The process often involves adapting various parameters to align as closely as possible with what I envision.

How do you think art can help us to better understand our relationship with nature?

Both art and science share the capacity to cultivate curiosity and awareness. They encourage us to notice and engage with the processes surrounding us, things we often overlook in our everyday lives. It’s about learning to observe not just static objects but processes in motion, things evolving and transforming over time. In this way, art and science are both ways of seeing and tools for teaching us how to perceive the world more deeply.

In your work Cartes mères, the landscapes that emerge seem to evoke imaginary worlds, but they are derived from the technological waste of our time. Is this transformation a way of reflecting on obsolescence and our disposable culture?

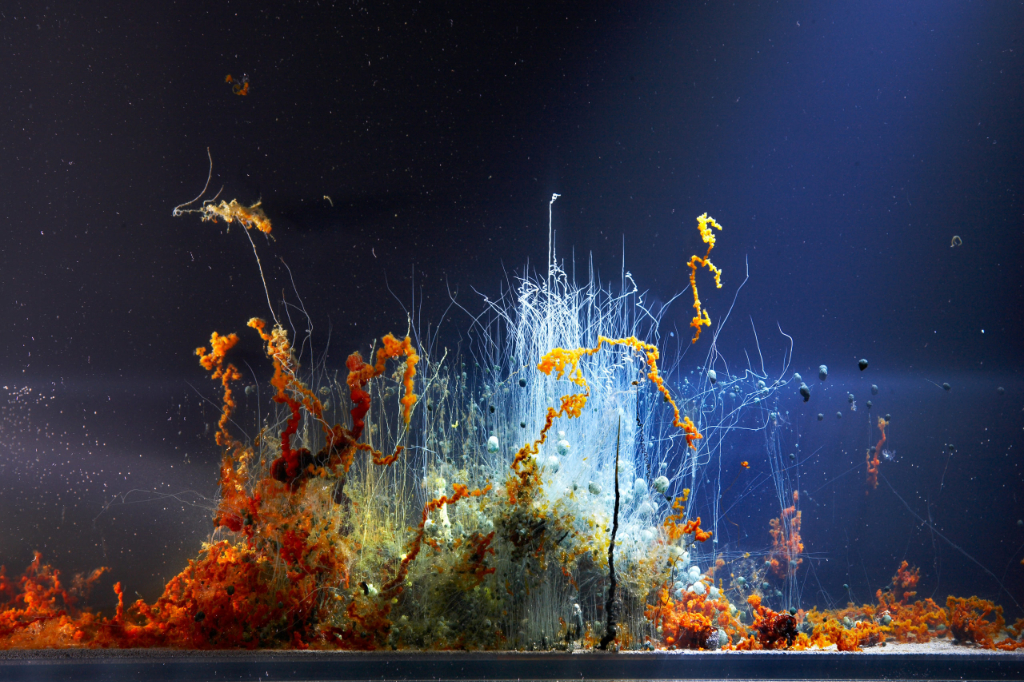

In my work, I strive to create pieces that appear fantastical yet are deeply rooted in reality through their processes. This paradox is especially compelling. The shapes in my pieces aren’t ones I’ve designed—they naturally emerge from the physics of our world. For instance, in Cartes mères, the landscapes are formed from materials like copper, tin, or silver, their shapes dictated by the inherent properties of these materials and the energy applied to them.

Electricity plays a central role in this work. The forms result from an electrolytic deposition process, and my contribution is the adjustment of parameters such as energy, distance, and time. The landscapes essentially shape themselves, and my role is limited to setting the conditions for their emergence.

What I find beautiful about this process is the way it blurs the line between the real and the imaginary. It reveals how many aspects of the real world are inherently imaginative, encouraging us to look more closely at matter and uncover fascination in the seemingly ordinary. This approach invites curiosity and exploration, offering a fresh perspective on the relationship between the tangible and the fantastical.

I imagine that since you’re not a scientist or chemist, starting to work with these processes must have felt like conducting experiments. Did you know beforehand that the results would be so striking?

At the studio, I’m constantly running small experiments, different ones simultaneously. These experiments feel like my palette, like the tools or materials a painter might use. Sometimes, something I experimented with years ago combines with a more recent test, and by following my intuition, I realise that it could work. It’s a process filled with trial and error.

I began experimenting with this particular area of work about four years ago, but the initial results weren’t very satisfying. Two years later, I revisited the idea, informed by other experiments I had done in the meantime, and the results were slightly better. That encouraged me to keep trying, repeating the process over and over until I found a setup or method that yielded interesting results.

I never know in advance how it will turn out—it’s more about building on intuition and the cumulative knowledge from previous experiments. There’s a lot of rehearsal, testing, and refining. I start small, running tests on a smaller scale, and then move to the final scale I envision. It’s a continuous process of going back and forth until everything feels right.

How do you ensure you keep a detailed record of your work as you go through these experiments?

I have to write down the parameters I’m aware of, but there are always elements I might not notice at first. Each project is different, but I typically document the process as thoroughly as possible. Often, I use video to record when it’s feasible. However, the experiment times were too long for continuous video recording for this project. Each small block took about three to four months in an electric bath, so video wasn’t practical in this case.

Instead, I took photographs every few days and kept detailed notes about the process. I recorded things like temperature, concentration levels, and the amount of electricity applied. The parameters vary for every project, but the process always involves meticulous note-taking and observing what happens visually over time.

Would you say that your landscapes offer a critical or poetic commentary on the fate of waste and the relationship between technology and nature?

Yes, there’s definitely an intention behind them. I don’t usually approach my work with a specific message, but I aim for the pieces to provoke thought and spark dialogue. Some people might interpret a clear message, while others may simply experience the work on a more abstract level. What’s important to me is that the pieces create space for reflection and encourage viewers to ask questions for themselves.

I see these landscapes as a reinterpretation of the romantic tradition in painting, where humans were often central to the composition. In my work, though, it’s a kind of nature where no human can survive; a romantic vision of nature in its purest, untouched state.

You recently presented the solo exhibition Aléas at the Wentrup Gallery in Berlin, which combined both older and newer works. Can you tell us more about this exhibition and the works you presented then?

For this exhibition, we showcased a piece from a previous series along with a new collection of 3D-printed sculptures. These sculptures are also currently on display at the Stelfingen Museum, near Stuttgart in Germany. This series explores morphogenesis: a field of physics where scientists study and describe natural shapes through mathematical equations. I use these equations as a tool to sculpt. For example, in this series, I started with the scanned shape of a real rock using photogrammetry. Then, I applied morphogenetic equations, such as those describing the formation of clouds. The result is a rock that seems to morph into a cloud, creating a poetic and surreal transformation.

The process reflects much of what I aim to explore in my work. Here, I digitally manipulate equations to act as parameters, allowing for a kind of “sculptural poetry.” The final forms are rooted in reality; they start from something tangible, like a rock, but transform into shapes that could theoretically exist yet don’t naturally occur in our world. It’s not about creating something purely imaginary but rather something that blurs the line between the real and the unreal.

For me, it’s fascinating to start with something as grounded and physical as a rock and apply equations that shift it into something as ethereal as a cloud. Both shapes have their own physical realities, the rock and the cloud, but combining their morphogenetic principles generates a new form that feels dreamlike. These are shapes born of reality, yet existing outside the constraints of our natural world.

Chamber Climatic is described as an ever-changing ecosystem. Could you share how you created this installation and what message you intended to convey through it?

There isn’t really a specific message; it’s more of a tool to encourage reflection and thought. In this piece, I worked with 3D-printed shapes designed to blend characteristics of rocks, plants, and clouds—shapes that don’t typically coexist. These sculptures are placed in a terrarium alongside a type of mushroom capable of decomposing the material. The sculptures themselves are digitally created and then 3D-printed using PLA (polylactic acid), a bioplastic derived from corn that is compostable. Certain microorganisms, including the mushrooms in the installation, are able to consume this material.

This work involves placing these sculptures in an environment that accelerates their aging process, essentially simulating the passage of time over just a few months. It raises questions about matter, the physical nature of artworks, and how we think about preservation.

For me, true artwork is less about the physical object and more about the digital file. The file can be used to 3D print the sculpture again, even if the original object deteriorates. The physical sculpture is intentionally subject to time and decay, but the ability to recreate it from the digital file opens up a dialogue about preservation, impermanence, and how we relate to materiality in art.

You’ve mentioned time as a key element in your work. How do you choose the materials or substances you use?

For the 3D printing aspect, I use PLA (polylactic acid), which is one of the most basic and widely used materials for 3D printing. As for the other elements, like the chemicals or mushrooms in this piece, I researched mycology. There’s a lot of current research on how mushrooms can remediate soils or compost various materials, even metals and heavy metals. This informed my decision to work with mushrooms, as they’re already being used by scientists today to transform matter in innovative ways.

Do you consider yourself more of a scientist than an artist these days? Or perhaps a bit of both?

I see myself as more of an artist, though there are certainly overlaps and correspondences between the two fields. The relationship to understanding is what differentiates them for me. While art and science share common ground in their curiosity and exploration, their approaches and goals are quite distinct. I don’t think the two can be completely merged—they complement each other but operate within different frameworks.

That said, I find it incredibly inspiring to collaborate and converse with scientists. I hope to inspire them or offer them a different perspective on their work, perhaps even spark new ideas. Still, the underlying ideals of understanding in art and science remain separate for me. Of course, the aesthetic aspect is crucial in my work, and that’s where the artistic side truly comes into play. It’s what defines my approach and distinguishes it from a purely scientific pursuit.

I know you have many projects coming up in 2025, but is there anything in particular you’d like to highlight?

Yes, there are some exciting projects. One of them is with Le Fresnoy, a school in the north of France where I was once a student and am now teaching for a year. Their system is quite unique; teachers guide students on their projects while also creating their own work using the same tools available to the students. Le Fresnoy, founded by Alain Fleischer, strongly focuses on cinema and new technology, giving it a distinct spirit.

For me, this is an opportunity to experiment with real-time simulation for the first time. I’m working on creating a video without a fixed duration, a piece that is continuously calculated in real time by a computer. What the audience sees is always new and evolving. This concept is central to what I’m developing at the moment.

What do you think is the biggest enemy of creativity?

I think boredom is the biggest enemy of creativity.

You couldn’t live without…

Maybe a computer?