Interview by Allan Gardner

Rosana Antolí’s work defies categorisation by media, moving between traditional and new media in order to understand and re-present the natural, rhythmic kineticism of the human experience. Her focus on movement comes from the concept of Social Choreography, referring to the ways in which the world affects and is affected by movement, extending to the natural ways in which our movements are determined by the movements of others and the inherent rhythm, or pace, of our environment.

This notion has extended throughout her practice, leading to a broad production of works untethered by media, freely exploring the notion of movement expanding to an abstract idea and contracting to an individualised series of actions. Temporality of movement is a consistent theme in Antolí’s practice, often realised through durational performance works as well as pictorial pieces tracking movement since lost to time. In turn, she manages to produce structures in which our awareness not only of present motion but of previous and future movements becomes omnipresent – all movements that have happened, are happening or will happen are happening all at once, recorded in unison.

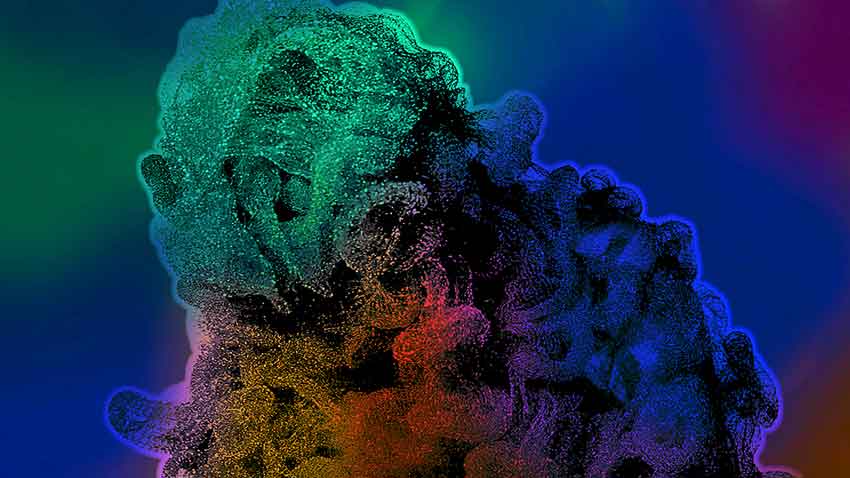

For a recent Tate Exchange commission, Antolí produced an immersive multimedia installation comprising sculpture, performance, video, painting and participatory workshops taking place across an ever-changing installation landscape. The work, titled The Kick Inside, The Loop Outside, was inspired by Turritopsis Dohrnii, the immortal jellyfish. Expanding on Antoli’s previous artistic investigation into the loop, or the cycle, this work explores a cyclical space as one which allows for (and is powered by) the variable. Variables in each cycle alter the landscape and create evolution; the interaction, the movement of the viewers, alters the space and re-defines it both aesthetically and structurally.

In the past, her work has taken on a more minimal approach whilst retaining the same interests in the ways that movements are tracked. 2017’s Everyday Symphonies, My Daily Objects Movements consists of a four-legged stool, one of which is propped up by a stone; on top of this stool are a series of gestural abstract marks made in acrylic paint.

Works like this go some way towards exploring the duality of movement present in Antolí’s practice, the way in which minor moments extend outward and protrude into the movement of other objects in the space. In this sense, object extends to individual, the chair perpetually falling and not falling, balanced, worn and marked by its minor journeys as it plays a role in the movement of others.

Part of what makes Antolí’s work with movement engaging is the way in which its communicability is explored from varied aesthetic and material perspectives. It allows the viewer to perceive their own movement and the multiplicity thereof by engaging participation as well as spectatorship. The time to move and the time to be still, decisions to make and decisions to be made for you.

Your work encompasses drawing, sculpture, video and performance, investigating movement to create patterns out of ordinary human actions. How and when does your interest in the human body and movement come about?

Movement always fascinated me. I got caught by the subject ‘of animation’ at university, and since then, I have been experimenting with different techniques and processes in my work. In the beginning, my interest was more formal, the aesthetic to see a painting in movement, or to give ‘time’ dimension to the narrative of an artwork.

Later, during my Master’s at the Royal College of Art in London, the question that arose was: ‘What makes us move?’ ‘Why we move the way we do?’, and I did my master’s dissertation about the topic ‘Social Choreography’, with the main interest in our daily gestures because even if these everyday actions are a minimum expression of ourselves, they can define identities and culture.

How do the different disciplines/formats you use in your work help translate your research into movement?

It is all based on emotion. It needs to emotion me, and then I can communicate this to the audience. Materials are very important because I need to choose how a process and action, something that is intangible, could be captured and translated into a new language.

It is not the same to represent certain movements on a canvas or with a sculpture that occupies another kind of space when it is exhibited. It has a presence and a dialogue that are more active with the audience.

Recently, for example, I read about Joan Miró (that is one of my artistic fathers), and in his writing, he described how an immobile object was for him the image of infinite movement. I find capturing to discover other solutions or points of view for the same question.

We are interested in your description of your practice as utopian in character and the absurdity and failure of the actions involved. Could you expand on that?

We, as humans, can’t ever do the same movement twice. Having said so, we constantly keep trying utopian actions condemned to failure, like the figure of Sisyphus. In my video work, ‘Everything is circular until is not’ participants were invited to spin a hula hoop eternally and to make each circle hoop exactly the same as the one before. This human stubbornness that makes us do something, even if we know beforehand what the result will be, is one of the sides that I find that give poetry to the artwork. Many of my artworks reflect this humanity. This will go against our own fat.

Another recurrent topic in your work is the loop, infinite or repetition, but also chaos. How do you reconvene these two apparently opposing concepts?

Well, I agree with the bases of Oriental philosophy that point to the equilibrium of opposites and how they become the same. The loop or the infinite repetition can just be achieved by machinery, but our actual paradigm tries to make us repeat our working days and hours, repeat actions during labour time, and it is against our nature. Our body and mind, the limitation that we have towards that mechanical function is our inherent resistance towards this system.

What has been one of your most challenging projects and why?

For me, the most challenging projects are always the last ones I have done. My last project was at TATE Modern in London. I was invited to take the fifth floor of the museum for two weeks. The challenge, in this case, was to conceive an exhibition with that duration of time, with a live performance every day for 6 hours in the space and to bring sculptures and videos to have a direct and active relationship with the visitor. It was a very demanding project conceptually and also physically in terms of building the installation.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

Comfort.

You couldn’t live without…

Dance… In/with all senses.