Words by Cathrine Disney

A theme that continues to weave through the work of Thought Collider, the experimental critical art and design duo, Mike Thompson and Susana Cámara Leret, examines what we often perceive as intangible, non-functional biological waste material of human life.

The duo express a belief that everything in nature has a purpose and is cyclical, yet as humans perhaps we do not fully understand the purpose or are not yet able to utilize our biological waste streams in the way in which nature has intended.

Although Thought Collider was accustomed to a more human-centric approach influenced by their design education, their interest in (bio)technology provoked them to reconsider our existence in a broader context as part of a much larger system, and consequently our impact on ecology.

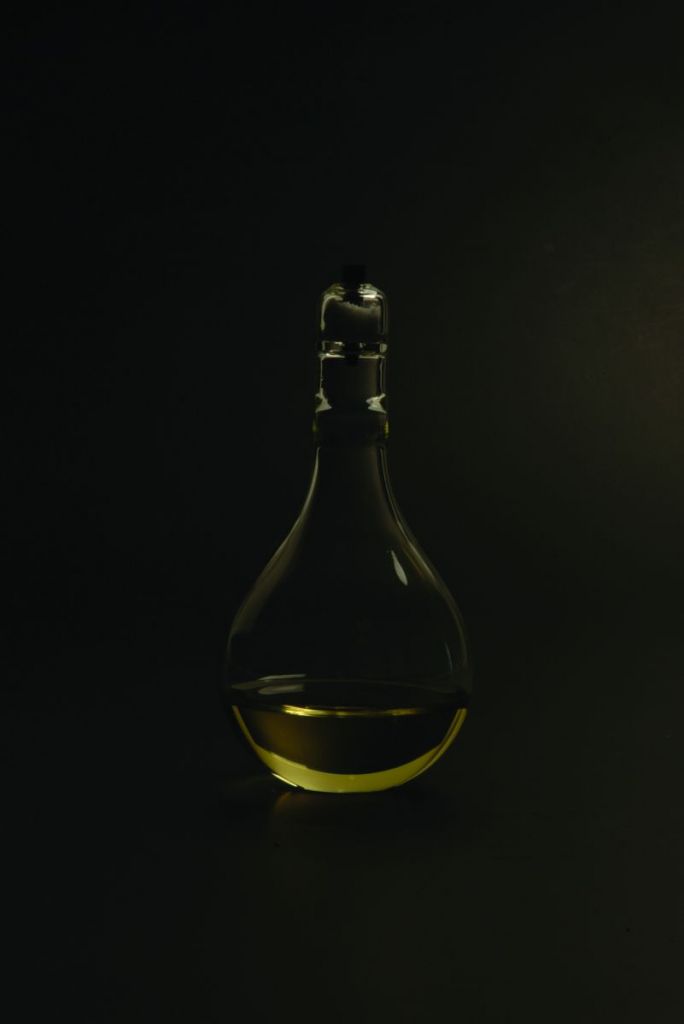

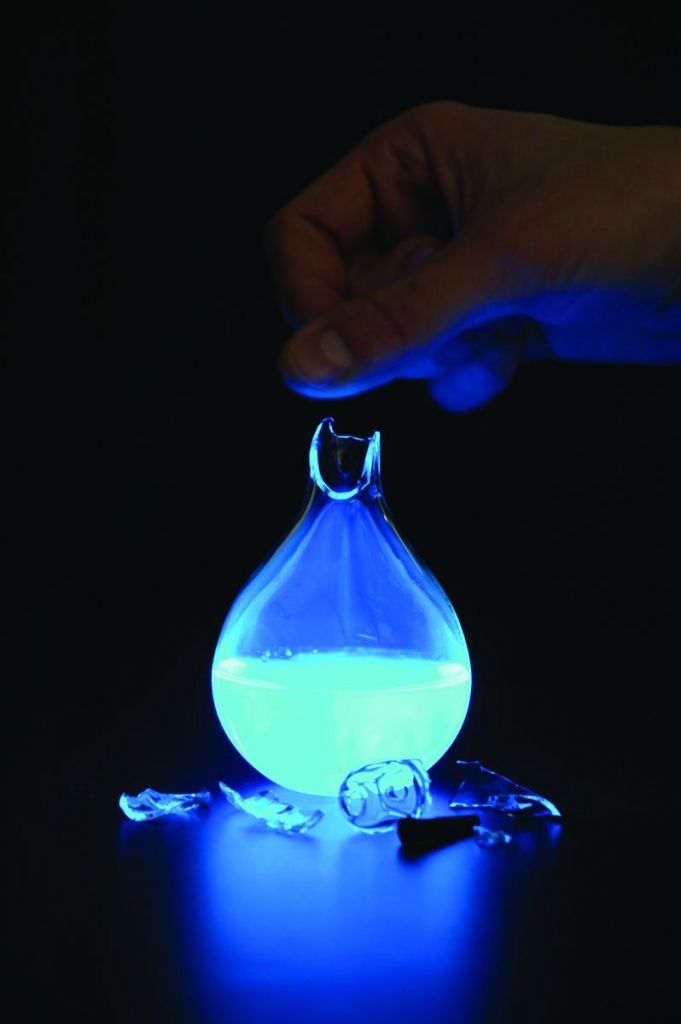

Inspired by a process known as ‘chemiluminescence’ – a blue glow – which is created when Luminol, a chemical used in Police Forensics to determine the presence of blood at a crime scene, comes into contact with iron, found in the haemoglobin of blood, Blood Lamp is a speculative design product that requires the user to supply their own blood to power the lamp and can only be used once.

In diametrical opposition to our ‘end user’ focused technological developments, through its inherent interaction, Blood Lamp forces upon us an awareness of our excessive wastefulness via energy consumption.

On the other hand; Thought Collider’s most recent ongoing project, The Institute for the Design of Tropical Disease, explores several intertwined research themes including Human to Insect Chemical Communication, Open Source / DIY Synthesis of Medical Compounds, and the Architecture of Insect Breeding Grounds.

The project’s main interest is in revisiting the strategies used to manage the spread of tropical disease through a more imaginative, rather than pragmatic, approach, by exploring the complex relationships that shape disease transmission on a molecular, human and environmental scale.

Motivated by emerging technologies, the work of Thought Collider delves deep into the quest for knowledge, meanings and values, continually probing alternative ways of experiencing and confronting the environments in which we exist.

What drew you into working in the intersection of critical design, emerging technologies and (bio)science and health?

If you were to look for a red thread in our work you could say we have an interest in the perceived value of surplus or waste materials, typically biological materials or those closely related to or generated by the body. That probably oversimplifies things, as what “we” deem a material is not necessarily tangible in a “functional” sense, for example when exploring the data potential of Urine in Aqua Vita, or biophotons as messages of life in The Rhythm of Life.

Our work then attempts to query this function-driven discourse by acknowledging that within nature, everything has a clear sense of purpose meaning there is no such thing as waste. So the question is, if these materials aren’t wasted, then what are they? What are “we”, as humans, missing? What do they tell us that we are not listening to?

Our interest in the “bio-technological” therefore comes from an urge to explore what it means to interact with living systems. Having an art/design education we were accustomed to a more human-centric approach to the creation of artefacts.

What fascinates us about the biological is that the human is only one component or construct within a larger system, therefore the actions or decisions we make have a ripple effect on the broader ecology. In this sense, we are interested in re-considering this position and the manner in which we interact and communicate with life.

The The Institute for the Design of Tropical Disease project appropriates and explores tropical diseases as a medium for art and design. Could you tell us a little bit more about the intellectual process?

The project, comprising a number of different, intertwining research streams, was motivated by the performative history of tropical disease, and interest in revisiting the different strategies used to manage and contain its spread. We felt there was a need to create a space where a different discourse could take place, based on a more imaginative rather than a pragmatic approach to tropical disease.

The UN, NGOs and big pharma, claim for the eradication of tropical diseases like malaria and in doing so we regularly witness stigmatisation of insects such as the malaria-transmitting Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes, or more recently Aedes aegypti with the outspread of the Zika virus.

These biocontrol initiatives, like with the genetic manipulation and eradication of species, are normally presented via the media through war-like accounts and this inspired us to revisit processes of colonisation on various scales; for example between the malaria plasmodium parasite, the Anopheles gambiae mosquito as its vector, and the human as its host.

In this sense, the project addresses air as material and metaphor, to consider the molecules involved in the communicative and evolutionary links between our skin’s odourants, the insect’s response and the parasite’s transit for survival. Working with atmospheres we want to rethink ways in which we designate ‘Others’; for example, malaria also existed in Europe and is not only native to ‘the tropics’.

In investigating the history of quinine, the bitter alkaloid found in the bark of the Cinchona tree, native to South America and used as an effective treatment for malaria, we have been revisiting tales of biopiracy linked to its harvest, smuggling out of South America and latter commercialisation.

This triggered us to experiment with the flavour dimension of bitterness, which we often don’t come across in our overly sweetened society, to also investigate the links between recreational and medicinal compounds.

Blood Lamp is a speculative design project that aims to raise awareness about the cost of power/energy. What biotechnical invention do you think will have more social acceptance or impact in real life in a not-too-distant future?

We don’t necessarily advocate for “a” specific technology. Instead, we see our experiences with technology as a means rather than an end. That said, if we respond from the perspective of Blood Lamp, we were attempting to shift the simple act of creating light back onto the individual so that they become an actor within the process of creating energy, as opposed to being the end consumer.

Currently, there’s a lot of hype around the so-called “democratisation of technology” and the maker movement, shifting scientific or industrialised practices into the hands of the consumer, and turning the consumer into a producer or researcher.

From our perspective, what is most interesting about this is not so much what the individual might choose to produce or investigate, but rather how they relate to the world around them and their direct experience.

These technologies are more than a means for creating, but rather tools for understanding or sensing processes, for example, the materiality of light understood through a biochemical process. In this instance, the distortion of the human body allows for a different entry point into discussing energy consumption.

Similarly, sensing technologies such as the Photon Multiplier Tube, employed within The Rhythm of Life project, challenge notions of what constitutes a ‘body’ and will lead to a vastly different understanding of health, drawing close attention to our body’s constant evolution in direct response to our lifestyle and diet. In this sense, the body can no longer be viewed as a closed system, but rather an extension of the environment.

You might say then that the most profound impact of biotechnologies such as the Photon Multiplier Tube, will not be via their application as tools, but rather in that they stimulate a different thought process and relationship with living material.

What directions do you imagine taking your work in?

The Institute for the Design of Tropical Disease and FATBERG are long-term researchers, so we will be spending the next few years exploring these themes and various sub-themes. With FATBERG, for example, a collaboration between Mike and Arne Hendriks, the island of fat must grow and we’re only at the very beginning.

Funnily enough, Arne and Mike don’t see themselves as authors of the project, rather agents of the fatberg. Moving forward the goal is to create a community of individuals who share this desire to understand fat, a community who too research and assist in constructing the island.

Aside from “berg” building, which is central to the project, there are several parallel sub-themes we are interested in, for example, how we might harness the sewer as a production system.

Similarly, within The Institute for the Design of Tropical Disease, we currently have two main research themes in Insect to Human Communication and DIY Medication. These are large topics in their own right, however, we aim to explore other related, yet unique topics, including the architecture of insect breeding grounds.

What perhaps links the two projects is that they are quite plastic, enabling us to move between various themes and media, operating in and outside of the traditional laboratory, gallery, museum contexts and layers of society. In fact, we are increasingly interested in this in-between position that we seem to be taking.

We don’t think of ourselves as designers or artists, and we’re certainly not scientists, though we tend to move in and around these classic distinctions. You could say that we are as interested in stimulating grass root initiatives as we are in infiltrating industry or challenging classic modes of knowledge production – for us it’s simply a quest for knowledge.

It’s about pushing conceptual and physical boundaries by activating society as contributors within our investigations to enact alternative ways of experiencing and thus understanding technology.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

Repetition.

You couldn’t live without…

Change.