Text by Gabriella Gasparini

My first month in Paris was crowned by an encounter with the city’s aesthetic libidinality. As I entered its streets and perforated its belly, I basked in its excesses. Piss-strewed alleys and keys to midnight parks, wine-spilt shirts and bon vivant prolapsing into the streets from the dim-lit haunts that dot the city like rubella. The city from above looks like a constellation of gleaming orifices, some parts more enlarged than others, some swelling and swallowing their neighbouring shitholes until it all looks like a heap of shiny, lubricated intestines.

This all got me thinking about aesthetics as an excess. A surplus. That which is not needed. Modern cities are shaped by their functionality. Take Singapore or Dubai – wide avenues and crisp angles, no excuses to get lost. They became agoras for would-have-been voyeurs, who are now instead forced out like cattle to the slaughterhouse, partaking in the futile rigmarole of wants that are always ingested but never digested.

Panopticons of leisure, where all desires are stripped to face value, for all to enjoy, out in an openness so bare even its polished glass menageries reflect back the same old truisms. Functionality over form. Or perhaps, form as functionality. A rejection of the surplus, for that, must be reified as desire. The excess of previous architectures now absorbed in the factory of domestication: steel, lard, and gapings of silicon swallowing all that’s beyond the pale – it is now a product.

The contemporary city is naked. It is shameless. It is made of transparencies that are as lurid as sewers but that offer no escape behind the truthfulness of filth. In this lurid place there is darkness, but there are no secrets said Victor Hugo of the sewers in Les Miserables. Opacity brings with it the knowledge that something, even if it is rubbish, is there. Now, the towers of transparency that cast shadows on our sidewalks haunt and taunt us with their conspicuousness.

There is nothing to see here. Except everything. Always. 24/7 and in constant production. The contemporary city is pillaged of its excess, for that surplus must be fabricated as the relentless need for the new object. The excess is no longer in the architectural forms we inhabit but in the minds of those who desire it. The surplus must be pathologized. Which means the surplus must be de-aestheticised at the macro level so it can be easily distributed, packaged and administered at the micro level – at a price.

And so here I am, finding myself enjoying spying on my neighbours through the nooks and crannies of old fatiscent buildings. Heavy drapes at arm’s length, ready for me to hide behind. The noises and stenches of people’s dramas and dreams now the backdrop to my quest for the aesthetic excesses Paris can offer.

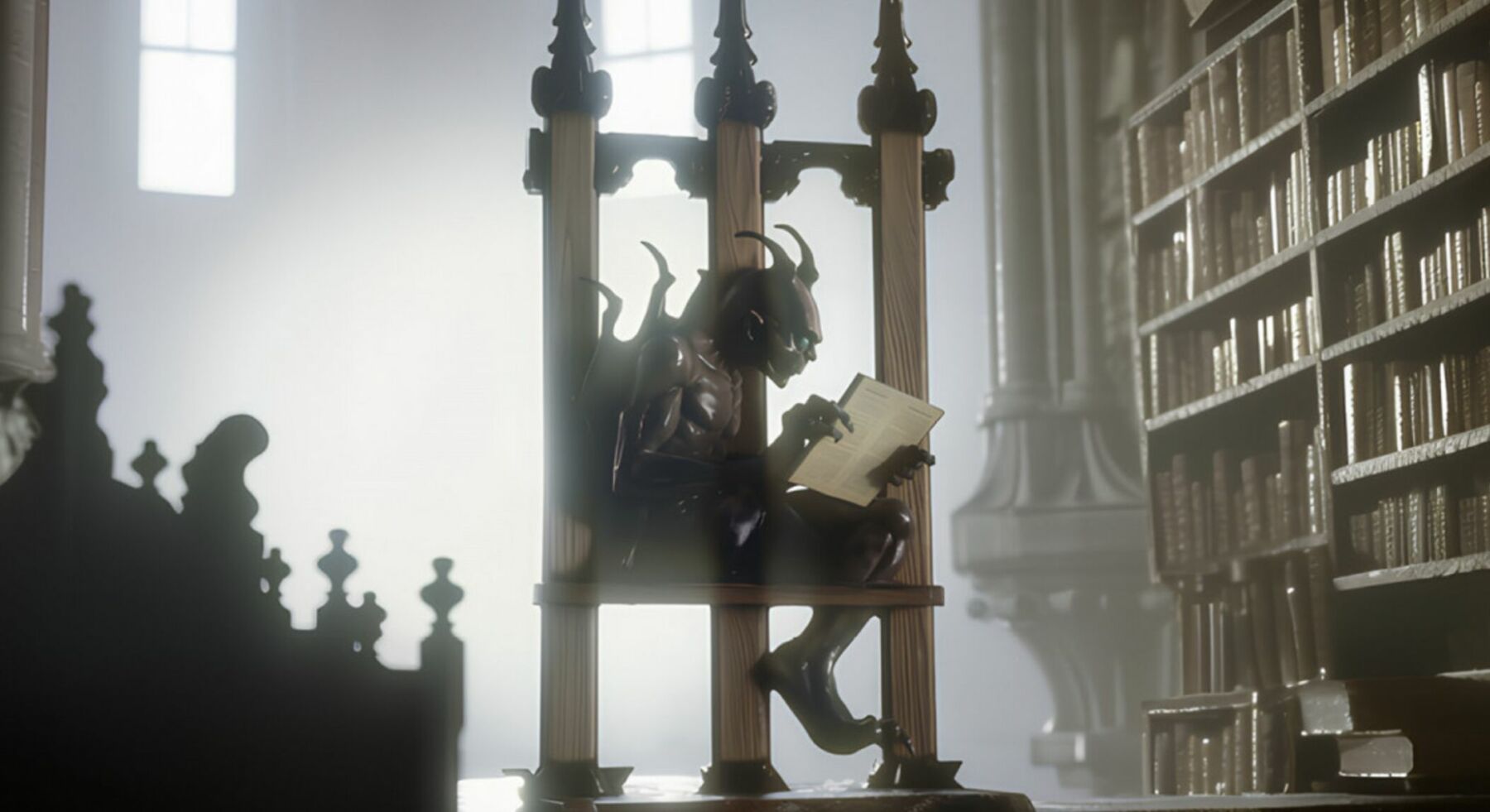

As all these ideas took form, I was presented with Ceci Tuera Cela (This Will Kill That), an exhibition by Eliott Paquet named after the second chapter of Victor Hugo’s Hunchback of Notre Dame at POUSH, Paris. The alphabet will kill the image, said Frollo, pointing at the book and then the cathedral. This will kill that. And yet language, even despite its formalism, still retains obscurity.

A word can mean two things at the same time. A sentence can be translated and warped. A speech can be misinterpreted – darkness and ambiguity still reign. Instead, in the transparency of contemporary architecture, there is no space for the sinister. No room for that which holds, frames, and nurtures the emptiness of space. What really killed the cathedral isn’t the word but the hollowness of the symbol.

When words become symbols, they are cleaned of any misinterpretation, they become hollowed of any doubt. Here, in these shallow containers, transparent and glossy like the high-rise towers that thrust from the ground, there can only be one meaning – there is no ambiguity, no excess, nothing anyone could disagree upon. They are symbols of our times. Bastions of a socio-political climate where complex concepts become flattened into symbols.

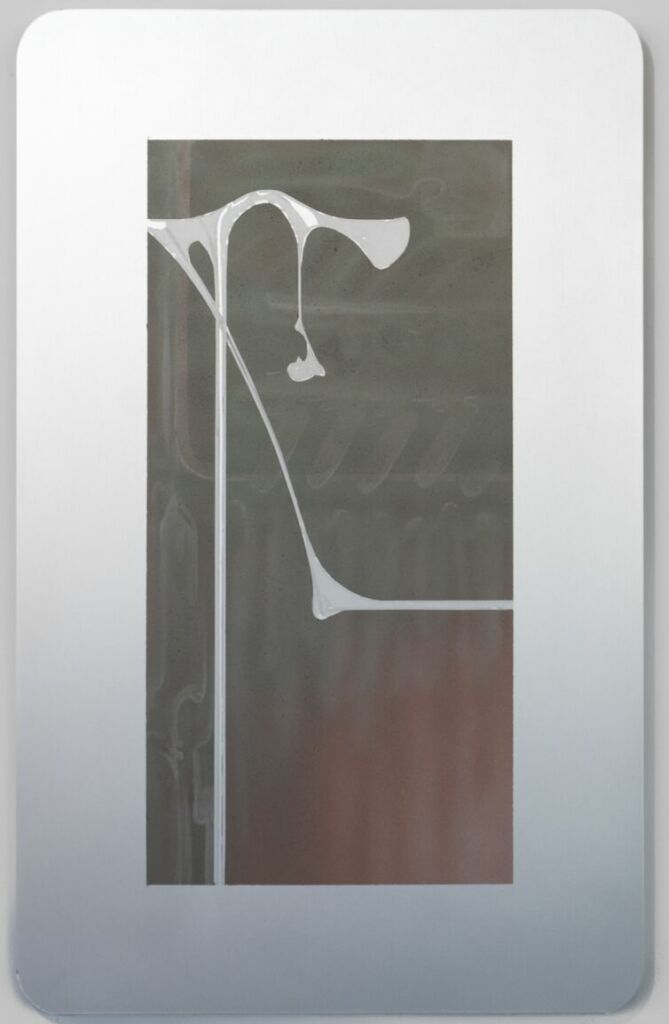

Paquet’s exhibition beckons for a return to the opacity of excess. The old aestheticism protruding like buds that break through cement, like cancers that metastasise over steel sheaths. Excess is a caged animal, a chimaera. A figure of the past trapped in the structures of today. The sewer overflowing, the truth now exposed. The real waste is not excrement but the way society has done away with anything surplus. It is not by chance that Paquet’s effluences grow so sleekly, so beautifully, so majestically out of the aluminium cages.

A testament to a wilderness that begs to burst through the overly-transparent functionalism of the consumerist age. And yet, in the age of production, it is precisely because aesthetics is a surplus that it must be stripped. Aesthetics is that which cannot be contained by the form of its components. That which cannot be reduced to its parts. Something which escapes the grasps of utility, or mocks that very utility by being so unnecessarily decorative that the utility itself is reduced to mere farce.

Kant called aesthetic judgements ‘disinterested’ because they cannot be reduced to our own basic needs and desires. Disinterestedness means we are seeing the object for itself, regardless of the purpose it may have. Aesthetics, thus, can be seen as the direct manifestation of freedom from need. It is, in a way, our ‘sewer escape’, a way out of the constraints of our consumerist society dictated by the myth of perennial scarcity and irreconcilable desire.

By systematically stripping the decorative excess from the contemporary city, by removing the gargoyles and stained glass windows, the sand-like spires and opulent vaults, by stripping the paint off fresco-vaulted ceilings and drowning the little passageways with artificial light, we don’t just kill form, we destroy our possibility to free ourselves from the rigmarole of fabricated desire. ‘Je Veux Ceci, Je Veux Cela’ – I want this, I want that.

Without the excess of the city’s form, we end up internalising that surplus, and so anxiety and dyspepsia, pepto bismol and benzodiazepine sewer sludge, cocaine rivers and plastic oceans, we fill the absence of obscurity by filling our own with the same objects that haunt us. But the city, like the body too, is shaped by the excesses of its form.

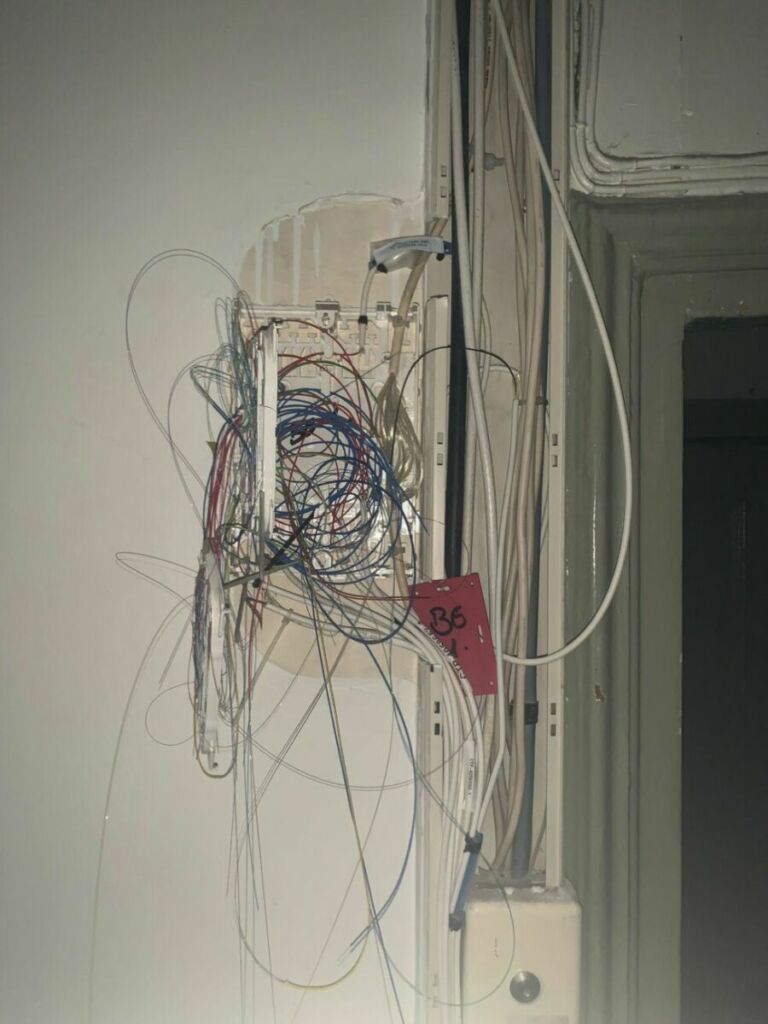

The tubes, valves and epithelial cells, like the sewers and deeply dug trenches of metro lines below ground, are not just containers for our gastric juices and communication networks but rather are the manifestation of excess. The protuberances of surplus are coded within our very own bodies: tears that flow for pains other than mere eye lubrication, appendixes that bulge without reason, tongues that savour kisses that bring no nurture, holes we penetrate to bring no progeny, arrector pili that only stiffen at the sound of notes that transcend the cacophony of everyday digestion, cancers that spurt and spread beyond the bounds of their own knowledge.

The body is excess. Let the city be it too.