Interview Jack Apollo George

Nicolas Guichard and Béatrice Lartigue center their practise around playful, interactive works, highlighting immersive and thought-provoking instantiations of contemporary technologies.

A swing that propels you into the depths of space, quasi-divine spotlights that embrace your hands with birdsong, a mirror that uses facial recognition technology to show you how happy you look. All their works rely on the engagement of the viewer. This is a high-risk, high-reward, continuously evolving way of making art.

When you stand in front of a painting, you can choose to close your eyes. You can always turn away. Likewise, when you are listening to a piece of music, you can always press next, turn off the radio, walk out of the concert hall. But when it comes to experiential art, the viewer cannot so easily reject the work. Refusal and criticism first require engagement. You cannot turn away from what you have not seen. You cannot stop listening to what you have not yet heard.

This reliance on participation is the secret ingredient that makes each and every experience of the work unique. The viewer becomes the ghost in the machine. Their body is an intermediary between their own appreciation and the artist’s intention. For Nicolas Guichard and Béatrice Lartigue, the response is where a lot of the magic happens. The unpredictability of the viewer’s interaction adds another layer of dynamism on top of the often generative nature of their installations.

The art is both in the piece and its reception. Their most recent work, Passifolia, commissioned by Hermès, consists of a large and dark empty room cast through with long beams of light—it looks like a warehouse filled with competing UFO abductions. Upon ‘touching’ the light beam, a visitor hears the sound of birdsong and feels the warmth of sunlight. A natural world is summoned, blossoming into that industrial, angular setting. The beam then narrows its focus, enticing further interaction.

Other works, like 2018’s Narcisse, highlight their ability to use sharp-looking visuals in quests to close the gap between the emotional and the digital. A join-the-dot cubist outline of a human mimics the visitors’ movements on a bright white screen, creating an interaction where the viewer can do nothing but stare at their own reflection, all while making it move in real-time. They both are members of the Paris-based art collective Lab212, which was originally founded in 2008 by a group of friends who had graduated together from Les Gobelins’ Media and Interaction course.

For those that are not familiar with your work, could you tell us a bit about your background and inspirations?

Béatrice Lartigue: I graduated in Fine Arts, then in Applied Arts – more precisely in Space Design. I’ve always been interested in the matter of scale. Since I was a child, I used to create miniature landscapes, and through rescaling, the possibilities became infinite.

I, therefore, have a strong interest in graphic art and storytelling. Comic is an important source of inspiration for me on how to symbolize concepts and how to deal in a simple way with complex stories that unfold in time and space. I enjoy the potential of the ellipsis and the blanks between the images, which allow the reader’s brain to make its own assumptions and mental connections. For instance, I especially appreciate Scott McCloud’s work and approach to deconstruction and narrative analysis.

Nicholas Guichard: I have a degree in Applied and Fine Arts as well, which taught me how to structure my ideas. As for inspiration, I often recall the pleasure I had when I played Lego as a child working on our projects. A pleasure that I found again in the flourishing of the web at its beginnings, then video games, and in certain currents of art history, kinetics in particular with Jean Tinguely.

Having grown up in the countryside, I was very interested in the relationship between art, technology and nature. Other members of the Lab212 collective have a more technical background. It is this combination of sensitivities to art, design and technology that has forged the identity of the Lab212 collective.

BL: I would also point out that one of the reasons that bring us together at Lab212 – beyond being friends and having related sensitivities – is the desire to share and the pleasure of learning by experimentation through research, prototyping… Many of us also regularly teach in Art and Design schools, participate as jury members, and monitor students’ theses, at Gobelins Paris, ECAL Lausanne, Beaux-Arts de Toulouse, etc.

You are a member of the interdisciplinary collective Lab212, can you describe the Lab212’s transdisciplinary experience in the context of art, science and technology?

BL: I think that Lab212’s transdisciplinary approach is inherent both to its constitution: in working together (generally in pairs or trios), but also to each of our personalities, our singular cognitive curiosities, and our need to constantly re-question our knowledge and experiences as a way to face the unknown. We favour regular collaborations with other artists, researchers… with whom we establish real connections to develop our projects, according to the specific issues of each work: the lead architect of the World Wide Telescope Jonathan Fay, the musician and violinist Chapelier Fou…

NG: For us, technology is a medium we exploit and divert to explore ideas and materialize intuitions. There is a constant back and forth between technical issues and the expressive intentions we seek to convey. Each project is different, for each one we implement creative and technical research in parallel.

BL: Our practice of new media and technology requires humility, a lot of research time, and many tests and failures to reach a result that we consider to be accurate. Our working process is similar to the scientific and research process; based on artistic and creative intuitions, we develop hypotheses which we will test and evaluate to express our original artistic intention to propose a meaningful experience which will concern and/or disturb the visitor.

How do you think critical/interaction design is contributing to a better understanding of current society?

BL: It is relevant to refer to critical design or design fiction, because our works respond both to entirely subjective and singular intentions that we carry as artists, but also simultaneously – and in a schizophrenic way! – to the interaction design imperatives. Indeed, in most of our projects, to ensure full completion of the piece, the visitor needs to establish contact with the system and understand the stakes, the rules involved…

This is why we often refer to the notion of repurposing (difficult to translate exactly in English), which evokes both the takeover and at the same time the matter of re-use, involving an economy of means and the adoption of accessible or Open Source technologies (such as Arduino for instance). Our work investigates technology but above all investigates the role of the artist in the piece and those designated as “spectators” or “visitors”.

They only take control of a slight part of the system exhibited, according to the rules we set beforehand, but they are free to modulate the rules as they wish, not to take part or to hijack the system or the experience from its initial purpose… And these variations are also the interesting part of our work: how visitors take hold of what is offered to them individually but also collectively.

NG: We do try to make our pieces as understandable as possible, so that the suggested interaction is as obvious as possible and that our purpose is understood. It is often in the interaction itself that we try to carry the message or the feeling we want to convey. It is a very special moment to see the audience absorb the work, and sometimes find unexpected ways to interact with it. Sometimes the most interesting interaction is between the spectators themselves, and the work becomes a means of connecting with each other. In any case, it is through these interactions that we wish to touch the visitor. Our installations are tools at the disposal of visitors, who must use them to understand or feel the meaning of the work. It is through this experiential dimension that we believe we can deeply touch the public.

BL: Through a distance setting, or a re-contextualization of an object (technical or not), we can question the common imaginary that inhabits this object through its symbolism, its function… (for example with the fans in Nebula and Appel d’Air or with the swing in Starfield). In the end, our work is related to the dismantling or re-building process evoked by Nicolas Bourriaud in his book Relational Aesthetics (2002),

“How trough installation propose a platform of interaction? Relational works of art do not ‘represent utopias’ but actualise them, creating positive ‘life possibilities’ as ‘concrete spaces’ rather than merely fictional ones.”

Passifolia is an interactive installation that creates a digital environment in which concepts of new technologies, nature and soundscapes are closely linked to physical performance; could you tell us a little bit about the intellectual process behind this project?

BL: Given the scale of this piece, Passifolia indeed engages visitors to a kind of choreography, or a live performance… they are highlighted in a space that is both closed and infinite (an entirely dark room, whose contours are no longer visible). In the age of medium dematerialization, our bodies are also partly disembodied or reconfigured with prostheses (headphones…) that we wear non-stop, increases, supernatural powers – which can not occur on our earth: replication, ubiquity, omniscience, mediumnity thanks also to big-data… Therefore, we play on these endless possibilities to develop experiences where time freezes, as interlude where emptiness recovers its full role. The visitor’s body acts as an agent, a vector, or a material for the experience that is performed.

NG: For Passifolia, we relied on the sensations of country walks or explorations of wild forests, trying to simplify these as much as possible while keeping only the essentials. In this project, the technology is not perceptible. This is the beauty of the work, which makes it almost magical. A great deal of research was necessary to achieve this fluidity in the interaction between visitors, light and sound beams.

BL: Each of our projects actually stages the body of the visitors. We concentrate on feelings and perceptions similar to memories. For instance, with Passifolia, we take advantage of the suggestive power of sound on our brains to create a shift: the room is empty but the space behaves like a living organism, with its own personality. We provide a blank page, which can be invested in or not. Using basic principles, such as a repetition of the same pattern in space (a vertical beam), it is possible to highlight its variations (its organic implantation in space for instance). In the end, it is the scale and the movement of the human body within this volume that will give life to the piece: drawing of vanishing points, slight variations… Subtle variations in the musical composition or various timings of beam feedback confer sensitivity to the piece and bring out the purely functional aspect: an action > a reaction that finally becomes quickly boring.

Here, for instance, the ambient music composition played all around the room evolves slowly (the generative music is played in real time through Ableton Live and a custom-made Max/MSP module), while for each beam a dozen of songs from the same bird can be played, which in the end produces a piece that is both ephemeral and unique, recreated with each incoming visitor.

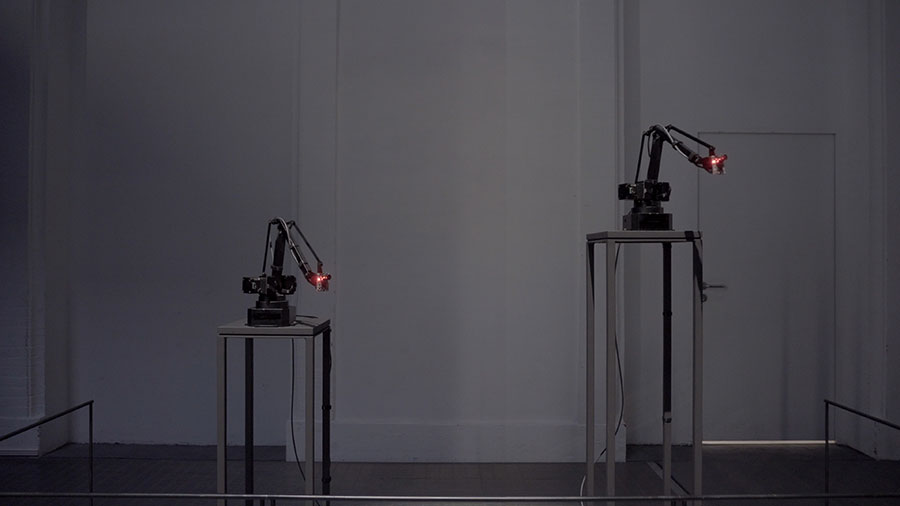

Fabula (2018), Narcisse (2018), and Cyclopes (2018) are projects that investigate what a human being is from a physical and emotional point of view using technologies like AI. We see the bionomy face-interpretation in Fabula; body-perception in Narcisse, and human-empathy in Cyclopes; how are new technologies affecting or changing today’s human behaviour?

BL: I believe that the strength of technology or technique is that it has always been part of humans, from the first prehistoric tools until now. We keep querying its legitimacy, but these questions have finally crossed history while technology and science continued to evolve and develop. The emerging issues are eminently social, political and ethical: how to determine whether a technology is beneficial or harmful to humankind, who has the true authority and expertise to do so?

What strikes me, and I guess like many citizens, is the concern about social gap and access to technology: what about access to hardware, network, training… when the daily issues are still related to fundamental needs? We now talk about soft power, the concepts and features of new media now feed and spread in a multitude of fields of our daily lives: culture, politics, medicine, law … from the most basic tasks (filling out an online form …) to the most sophisticated (automating the optical detection of medical pathologies on an X-ray …). While the idea is not to succumb to dystopia, there is indeed a feeling of a latent accelerating movement.

Humains design technology integrates it into their daily life, and then adapt their behaviour in reaction. However, like humans, these technologies are not perfect, which makes them “beautiful” in a way, and also provides some fragility and therefore a sense of humanity. Our artworks are not meant to be pedagogical, or to bring answers, however like most artists we usually combine our work and exhibitions with talks and round tables to exchange on these matters. We also design and lead many workshops for a large audience (young audience, “sensitive audience”…).

These moments of debate and vulgarisation allow us to dissect the issues and dynamics involved, and to (re)take control of the technologies and tools that shape our daily lives – often in non-visible ways. To illustrate this, in collaboration with the Centre Pompidou in Paris, we have developed the application Split, aimed at a young audience, to introduce simple concepts from programming (the principles of functions, variables, randomness, etc.), through the real-time generation of trees and plants that everyone can keep and print out on paper, like a digital herbarium (this application is available for free on Android and iOS platforms).

What directions do you imagine taking your work in?

BL: In order to extend these initiated fields of exploration, I would like to pursue the matters related to light and sound, and to emphasize even more the dialogue with the place in which each of our pieces are exhibited. Also, perhaps more particularly the aspect of itinerancy, as these pieces are regularly travelling around the world and this is not insignificant nowadays [in this very particular context of the Coronavirus] culturally, environmentally, and philosophically…?

NG: I would like to work on outdoor projects, interacting with nature, landscape and humans. I also question myself a lot about the ecological impact of our works, and for this, I admire the work of Theo Jansen, who finds a way to create works that are fascinating in every aspect whilst having a very low carbon footprint! I don’t know how to do this in my work, but it’s a direction.

BL: I must say that on this point, Nicolas, both challenges and inspires me! I admire his tenacity and his commitment to thinking about alternative solutions to go further in our commitment and therefore, in our intentions.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

BL: All things that seem urgent but not important. Also, the administrative and time-consuming work, which unfortunately is essential in our daily practice (accounting, schedules, emails…).

NG: Fear, fear of failing. Conversely (because one has to be positive!) I think the best friend of creativity is pleasure. Pleasure in what one does is passed on in the process and is reflected in the result.

You couldn’t live without…

BL: My relatives, my garden, my comics and the birds (but not necessarily in that order.

NG: In the confinement context due to Covid19, which encourages us to mention the essentials: my companion, my cat, the sight on the mountain I can see from my house… an internet connection and my computer (still)!