Interview Lyndsey Walsh

With the many impending crises looming over humanity, it is difficult to imagine what the world of tomorrow may be like. Our reliance on technological innovations to envision a possible future where life will be better has become creative fuel for artist and designer Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg. In her practice, Ginsberg sets out to creatively critique and ask what different versions of better mean and who will benefit from these possible realities.

Coming from a background in architecture, Ginsberg has been inspired by futuristic thinking and topics emerging from synthetic biology, which caused her to shift her creative practice into areas related to speculative and critical design.

A graduate of the Design Interactions Masters programme at the Royal College of the Arts, Ginsberg has continued to pursue creative ventures and transdisciplinary research practice. She has not only collaborated with scientists, artists, and institutions from all over the world but has had notable publications such as her edited book Synthetic Aesthetics: Investigating Synthetic Biology’s Designs on Nature.

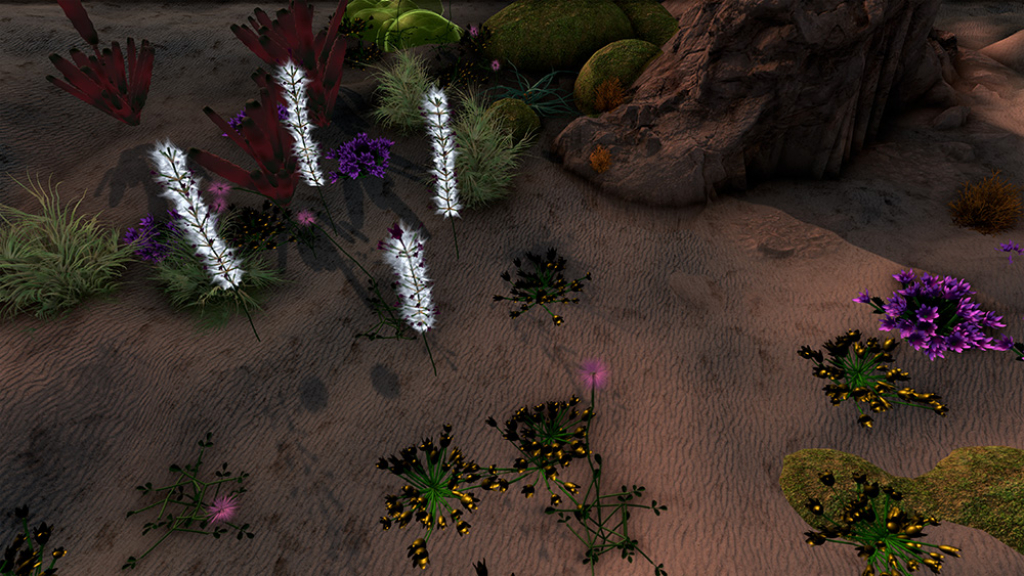

Her work Designing for the Sixth Extinction seeks to rearticulate the role design plays in the field of synthetic biology and opens a window into a possible world field with biotechnologically aided surreal landscapes. The work was last featured in STATE Studio’s exhibition Hypertopia, which sought to reflect on artistic proposals that confronted the major crises of our time.

In STATE Studio’s Digital Field Trip with Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg and Josef Settele, Ginsberg discusses the positioning for Designing for the Sixth Extinction as a confrontation to a type of solutionism emerging from society’s desire to fix ecological problems with technological innovation. While solutionism holds design and technology as a saviour for impending global issues, Ginsberg critically reads into the oversimplification of the complexities involved in solving the problems of our planetary crises.

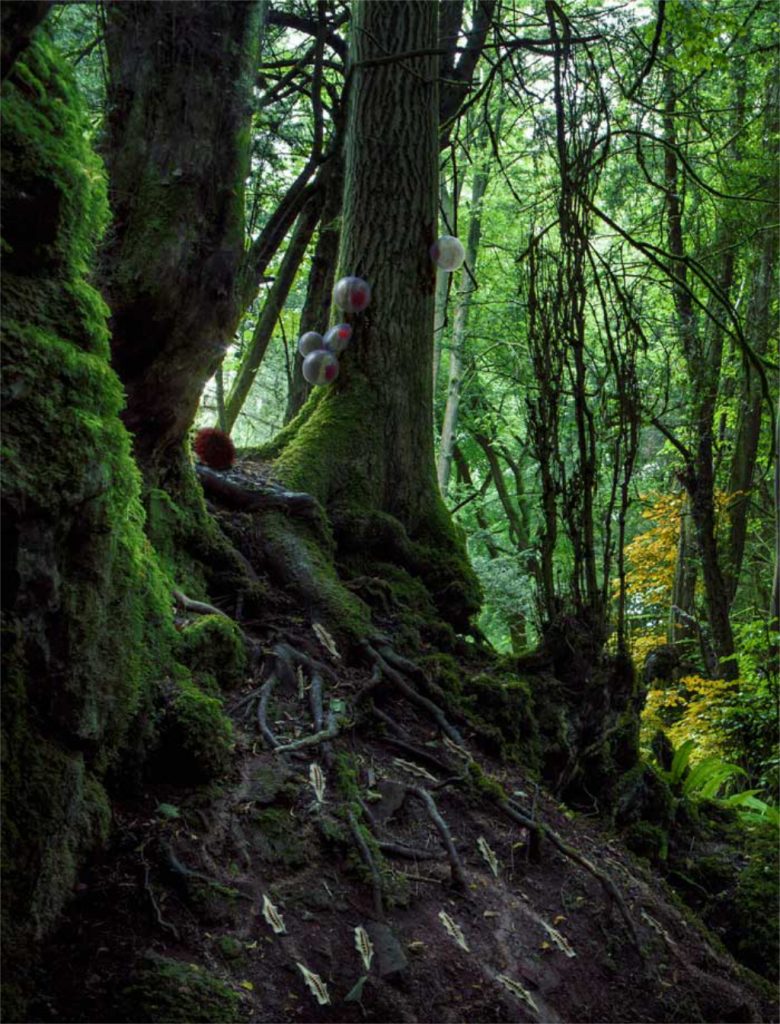

Upon reflecting on Designing for the Sixth Extinction in the age of the current and growing ecological crisis, Ginsberg’s work continues to be highly relevant and critical of how we can make the world “better”. In her upcoming work with the Eden Project, Ginsberg is creating a new permanent outdoor installation with a garden specially designed to cater to the needs, wants, and desires of pollinators.

The garden aims to act in opposition of the traditional notion of a garden, which sets out to meet the needs and desires of humans. The work will be accompanied by a website where people can use specially designed algorithms to create their own planting schemes using local flora and will debut in the Fall of 2021.

You are an artist whose works cross the boundaries between fiction and reality, the future and now, as well as art and science. For our readers who may not be familiar with your work, though, can you tell us about yourself and your practice?

My work explores our fraught relationships with nature and technology. We might think of them as opposites, but they’re not: they’re both things that humans have made to make sense of the world. I use technology to understand how we look at nature as something other than us and to think about why we create technology that further distances us from the natural world that we are a part of. Infused through all of that is my ongoing interest in design.

I describe myself as an artist now, but I have a very strong interest in design. We design to make things better for ourselves: to improve our circumstances, and I think, since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, we have increasingly used that idea of design to solidify this barrier between us and our natural environment.

We imagine that ‘better’ lies somehow within this artificial world. To explore these ideas, I create installations and quite complex projects that bring together large teams of experts and practitioners from many different disciplines, often pushing the boundaries of emerging technologies to ask questions of them.

What was the moment in your career that drove you towards working in this intersection between synthetic biology, technology, art, and design?

I did my first degree in architecture, and I lasted four months in an architecture practice afterwards. I realised that this profession was not for me. I am just not that into buildings! What I realized did fascinate me was this question of design and the impact that design had on the way we lived—the way it shapes our lives. That led me on a winding path.

I started working in urbanism at City Hall for the Mayor of London, where we were thinking about the future in fifty or hundred-year leaps, and that was my first introduction to thinking about how to design – and designers – actually shape the future and how it’s political.

I ended up going to the Royal College of Art in 2007 to study in a very new Masters’s programme called Design Interactions. The department was experimentally using design as a critical tool to explore the implications of emerging technologies. What it was offering was so far from anything that I even understood I decided to leave architecture and leap into this new space.

It was there, under the supervision of Tony Dunne, Fiona Raby and the other tutors, that I started looking at biotechnology. Then, in January 2008, my friend and collaborator Sascha Pohflepp, who very sadly died last year, came back from Berlin.

He’d been to a meeting at the Computer Chaos Club, where Drew Endy, a synthetic biologist from MIT, had been giving a talk about introducing this new field, which I had never heard of it. Sascha said to me, “I think you’d find this amazing”, so I started reading more about synthetic biology.

I saw this new field where engineers, bioengineers, and synthetic biologists were going to become designers because, essentially, they were describing what they did as design: the design of living matter. I began to wonder if they are going to be the designers; why am I studying design? What will I be doing in the future? What will a good design be? Who will get to decide that? Those first questions really set me off on this path.

You have worked with many different scientists and institutions all over the world when creating your projects. What has been the most interesting or surprising thing that has emerged from these transdisciplinary collaborative relationships?

I think the creativity. I don’t have scientific training. I did a mixture of arts and science subjects in school, but I am not a scientist. I think what really surprised me, and something that I learnt on the Synthetic Aesthetics project was the way that science is projected to the world is very different from how scientists do science.

In our Synthetic Aesthetics book, there’s a lovely chapter by one of the pairs of residents who talked about the issue of “day science” and “night science”.

For the scientists involved, it was really surprising to spend time in a design company [IDEO] and see that when the designers were at the stage of the project when you don’t know what’s going to happen or when you’re looking for creative ideas, and everything is thrown on the table, that moment is celebrated as part of the process.

However, in science, it’s kind of kept under wraps. I also think that failure is hidden more in science, and that’s also connected to how some real keywords have different meanings, which has ramifications for how we collaborate across disciplines.

One is ‘experiment’: if I experiment as an artist or designer, it means I don’t know what the answer is, and I don’t know what I am looking for. It’s a moment of playful freedom, whereas the ‘experiment’ in science is a very different thing.

It is a way to close down options in a way in the process of verifying a hypothesis. We use these words quite freely, but their meaning is greatly different between the two groups. Being able to understand that is key to making these kinds of collaborations work.

You have said about your upcoming work with the Eden Project that you want to make artwork for pollinators. How do you approach these more-than-human interactions to cross this species divide in your artistic practice?

My forthcoming commission for the Eden Project is about pollinators. Instead of making something about pollinators, I suggested making it for pollinators. I was given this huge patch of earth to build something. I proposed to make a garden, but a garden that wasn’t for human aesthetics or enjoyment; rather, it was for pollinators.

That brief presents a lot of really interesting questions. Can you design just for other species? Is there always a human impulse in design, and is it ultimately always for human benefit? I think it’s very difficult to design not for humans because we are part of the natural world.

For this project, I am really curious to explore this idea of ‘more-than-human’ design. We are designing an algorithm – I am working on this part with a wonderful string theory physicist, Przemek Witaszczyk.

The algorithm is designed to optimize planting for pollinators, maximising the periods with flowers in bloom, enabling a diversity of plants from a database that we have curated, and arranging those plants in ways that may be more attractive to pollinators.

It’s a really interesting problem: What will the garden look like if you are not prioritizing human aesthetics? Where do we stop making choices? The garden will be planted at Eden in September, and we are going to put the algorithm online then too.

The project is supported by the Garfield West Foundation, Google Arts and Culture, and the Gaia Art Foundation, and their support is enabling us to build a website where users will be able to play with this algorithmic tool and generate their own unique plantable pollinator artwork schemes.

A more ambitious plan is embedded within this, which is developing an approach to creative activism. Users can generate a scheme, plant it, and have their own edition of the artwork for pollinators growing in their garden.

You originally began working on Designing for the Sixth Extinction around 2013. Since then, we have seen more and more species suffer at the hands of the growing ecological crisis. How do you feel now about people interacting with your work vs when you first debuted the piece?

That work was a response to a conference I attended about the future of nature, organized by conservationists. It was the first formal dialogue between synthetic biologists and conservationists, and I knew little about the ideas being surfaced there around protecting or preserving or rebuilding the natural world using synthetic biology.

I think the Sixth Extinction project takes on a different position now in some ways. I used this as a vehicle to talk to synthetic biologists at the time. I was reflecting on their discussions about synthetic biology as a form of solutionism to the ecological and biodiversity crisis, and it was a really useful vehicle to stimulate debate within the field.

And now, I am curious how people respond to it eight years later. Those ideas in synthetic biology have not gone away. At the time, I was accused of it being Utopian by people in the synthetic biology field, who suggested the public may be disappointed when the engineers failed to save nature in the way my hyperreal images alluded to. Today, there may be a shift towards the sense that there is nothing else we can do and a grim acceptance of more technological solutions.

Your artworks and projects often focus on these notions of “better”, whether this is a ‘better’ design, ‘better’ organisms, or ‘better’ environments. What do you think about emerging visions of ‘better’ in our post-pandemic world, and who do you think will be impacted by these possible versions of ‘better’?

There is no one ‘better’. Better for some will always be worse for others to paraphrase Margaret Atwood in The Handmaid’s Tale. Better is subjective. There is a post-pandemic drive to ‘build back better’: even Joe Biden’s presidential website is “buildbackbetter.com”. Better for whom? Who decides? For these questions, there are no correct answers.

I would argue that we need to create a world that’s better not just for humans and not just for different groups of humans but also for the ecosystems we rely on and are a part of. Better doesn’t have a moral value to it.

The idea of Progress was about uplifting all of humanity with knowledge. But better doesn’t have such aspirations. It is simultaneously powerful and meaningless. It needs a definition, and each of my works is trying to present that problem or reveal it in some way.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

Admin and my inbox. The time spent managing creativity instead of the time spent creating.

You couldn’t live without….

The natural world.