Interview by Juliette Wallace

From the catwalk to the London Olympics, street protests, cultural heritage sites and the world’s most important museums, few artists have treaded such expansive ground and brought to life so many realms of our socio-cultural spheres as the UK-based gods of green, Ackroyd & Harvey. This year the crop cultivating couple is celebrating their 4th decade of one of their most iconic artistic practices: Photographic Photosynthesis, and we here at CLOT are excited to have had the opportunity to interrupt their busy schedule as they prepare for the Biennale of Sydney to talk to them.

Ackroyd & Harvey are prolific artists with an output that ranges from crystallising whale bones to adorning archaeological findings, replanting the acorns born from Joseph Beuys’ 7000 Oaks to creating a large-scale slate representation of Fibonacci’s golden ratio, but their grass works have been a constant throughout their creative development and have captured the imagination of a global public in a way that transcends the boundaries of art, environment, activism and even fashion (Vogue is a big fan). It is their equal dedication to medium as well as content that allows Ackroyd & Harvey this privileged position, one which relies upon the harnessing of and surrendering to time.

The couple first began collaborating in 1990, at which point the artists had separately been experimenting with grass, but neither had realised the living material’s full potential. It took a shift from a philosophical approach to a more scientific one to truly harness the medium’s power. In the mid-90s, they embarked upon a thorough, and time-consuming research project to understand grass and its properties better and, eventually, to find unique specimens (e.g. the ‘ever-green’) that propelled their artistic practice into a new realm. The result has been a steady flow of ground-breaking works that communicate through both the aesthetic and the conceptual.

I remember my first encounter with the Photographic Photosynthesis pieces, whose 30 year birthday we celebrate. It was in the mammoth cube area at the far end of the HangarBiccoca in Milan in 2011 for the Terre Vulnerabili (vulnerable lands) exhibit. Spanning a near 8 metres of the unthinkably high, naturally lit vault, the works had an immediate impact, one which continued to be immediate upon second, third and fourth visits to the show.

I was faced with a towering image of an elderly woman’s drooping but beautiful face emerging from a bed of various shades of earthy greens against a stark, grey, concrete wall. Once it clicked that the green – which, unlike the usual effect of the colour when used in portraiture, gave the feeling of life rather than death – was made up of thousands of blades of living grass, the work took on a new meaning which continued to evolve upon each visit. As the grass grew, the image became sharper until, finally, nature took a turn and the blades yellowed and died. It was a uniquely peaceful experience, watching in microcosm the passing of time, the development and eventual disintegration of life, all taking place over one fixed image.

As both artists and staunch environmentalists (in 2019, they co-founded Culture Declares Emergency in response to the climate and ecological emergency), the couple has been able to apply this wondrous mastery of grass to countless projects, most recently reviving their fabulous faux-fur grass coats, originally displayed at the Lynx anti-fur environmental fashion show in London in 1990, last year at the UK Extinction Rebellion protests which garnered them and the movement a lot of attention. We have no doubt that their contribution to this year’s Biennale of Sydney will be nothing short of breathtaking, and we can’t wait to see what the magi of meadow come up with for the occasion.

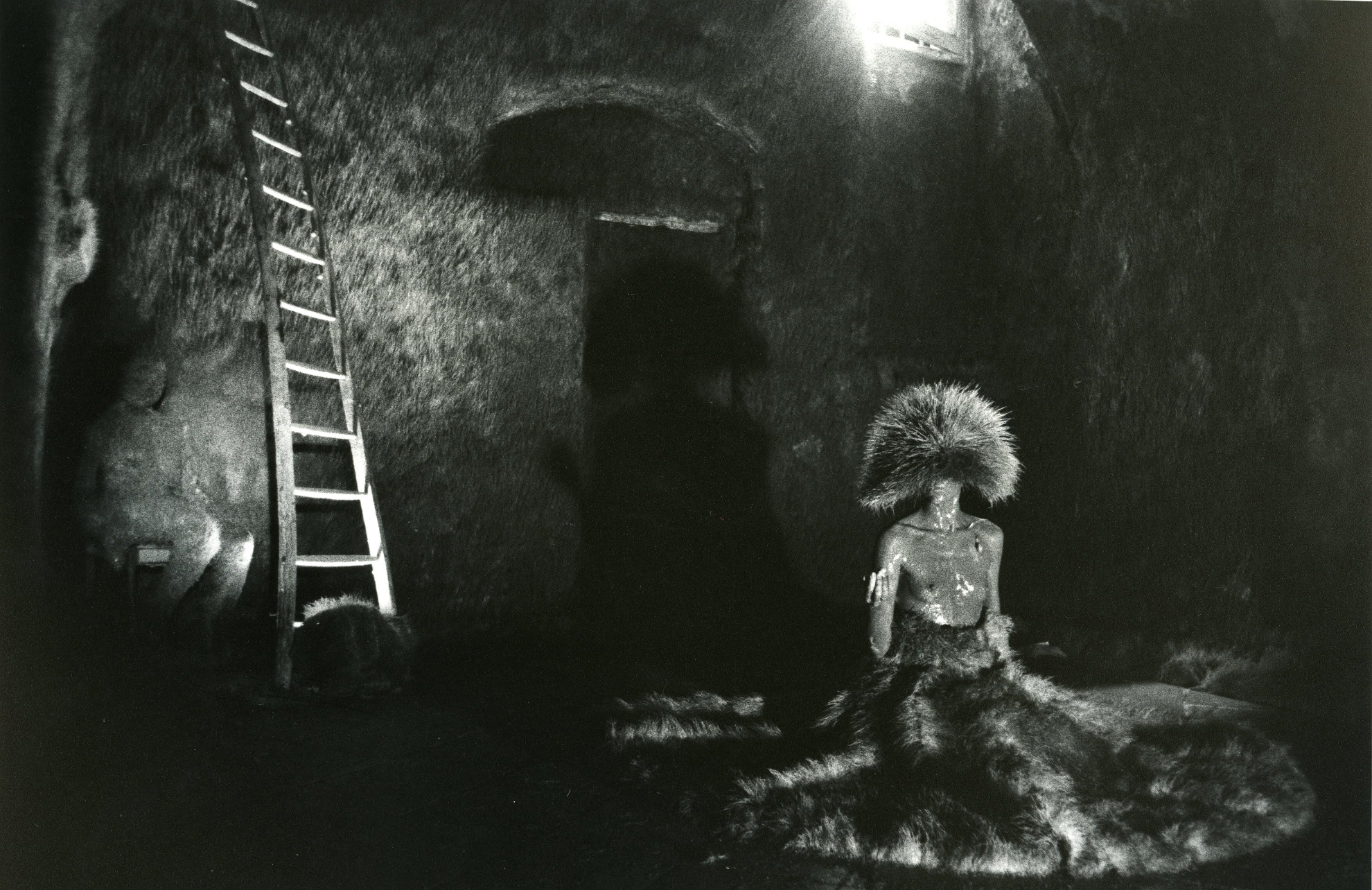

Right: Testament. Image imprinted through the process of photographic photosynthesis. Regrown for “Terre Vulnerabili” exhibition 2010. HangarBicocca, Milan, Italy

What would be your “Ackroyd and Harvey for Dummies” opening lines for those who aren’t already familiar with your work?

We describe ourselves as “artists and activists”. We work across various fields and have many different themes within our work. A lot of it is stimulated by observations of the natural environment around us which has led us into activism and the issues around climate change and societal issues of how we’re living on this planet. Our work is also informed by history, biology and climate science. We’re not a gallery or commercially oriented – we’re coming at it differently. The processes of organic and inorganic growth are where we keep alighting back. That’s our secure place.

I read that you were working with grass for a while before you realised its true potential as a medium. Was there a fundamental event in the evolution of this grass-tistic practice? And how is your approach to the medium changing through the projects you bring to life?

In 1990, a few months after we met, we collaborated on a project in a village in northern Italy called Bussana Vecchia. There was an electricity to our experience there and being with each other. That was when we started to fall in love. It was an artist’s community where we literally squatted. We had this vault-ceilinged room, a small budget, and some grass-seed leftover from a previous project. There was a quarry around the back of the village that had a clay substance that we could mix up. It was this landscape with cliffs where trucks were going in and out of the clay pit, pulverising it. We shovelled this pulverised clay into our bags, and this became the growing medium for our seeds that we covered the interior space with.

We intended to bring a material – grass – associated with the outside inside. And subvert perceptions by growing it from seed vertically over the walls. We were very playful. We grew this circle of grass that we pinned on a ruined church opposite that then became a clothing garment, we planted some leftover seed in a bowl that became a hat, Dan grew some books (that was part of his earlier practice). We brought all of our techniques and expertise into it. But it wasn’t just about that: it was a place with an alchemist energy to it. There were these magical moments hovering left, right and centre. You would suddenly have these visions. It was like a crucible.

The photosynthesis portraits weren’t a “eureka” moment. Still, we had this age-warped ladder that was handcrafted against the back wall in the space that had this young skin of grass growing over it, where we had very directional light from a big window and one halogen bulb that we lit the space with. The ladder cast a steady shadow onto the wall of grass. When we moved in to do some maintenance, we realised the shadow was imprinted in this bright yellow grass – it’s an obvious thing in that if you leave something on a lawn or a patch of grassland when you move it, the grass is yellow as it’s lost its chlorophyll – but it was through conversations that we had then that we realised there was something one could do photographically using this medium. A year later, at Le Fresnoy in north France, we first experimented with using a projected, negative image onto a wall of grass.

How do you produce a collaborative working environment? What are the guiding premises that ensure the integrity of the project?

I think we both have an innate trust in each other’s processes; we now have 32 years of experience working together. As a result, we’re generally adaptable, and we balance each other out: if one of us is particularly anxious, the other keeps a cooler head and vice-versa. That’s a gift we hold between us. We’re also both very good at approaching what we do and saying: where’s the risk? And identifying it. That is something you need to be aware of: what any potential problems could be before they begin to appear because when you actually see them, it’s normally too late (indeed when working with living material), so you’re always covering yourselves and staying adaptable.

How would you define your personal relationships with grass?

You have to really love and respect the material. If you don’t, you wouldn’t be working with it. There’s almost a sense of awe. Grass is arguably the most successful flowering plant on this planet. Some people argue that grass has been so successful that it’s put man at service to ensure that grasses continue to survive. I once heard a brilliant botanist say: grasses have got us working for them.

Your grass works are living things that change and evolve over time. How do you factor this into the aesthetic of the pieces and is there a ‘perfect moment’ during the evolution of the works?

There’s a moment when we stop projecting the negative of our photographic photosynthesis works when we step back from the piece and see the manifest positive image in all the exquisite hues of green and yellow. Often those are perfect moments. But there will be a change. That is inevitable. We can never completely arrest and fix the image. We accept the eventual demise of the vibrant living grass skin as it is exposed to the elements and the passage of time for our large-scale exterior pieces. We have to accept letting go of our attachment to the vitality of the work and appreciate the stages of decay and demise.

In your Photographic Photosynthesis portraits, is there an element of memento mori (or perhaps existential senescence) in what you do, i.e. the speeding up of, and therefore affrontation with, the human ageing process through the life and death of grass?

Years and years ago, we came across this notion of “vegetal resurrection”. It was something that the Egyptians were interested in. They would create these reliefs of Osiris (the god of vegetation), planted with Nile mud and wild grasses or some barley and wheat, and they would sprout inside the tombs. In some ways, it’s literally bringing the image to life. Something happened recently: we have a friend, Liz Jensen, who’s a writer and her 26-year-old, very beautiful son, IggyFox, (an activist and biologist) unexpectedly and shockingly died of a heart attack. We grew his portrait, and it was the first time this had ever happened in this way. There was this sense of him almost being brought back to life. It was very moving.

We can’t quite describe it, really. In that sense, with Iggy, there’s such a presence, a molecular presence. They’re very ghostly the portraits – like an apparition. On a molecular level, the structure of the chlorophyll molecule itself is very similar to the heme molecule in our blood. Yet, chlorophyll has magnesium at its centre, whilst there is iron at its core in our blood. So there’s something akin to our blood of life and the substance of life in plant matter.

You’re currently in Australia working on a piece for the Biennale of Sydney; can you tell us anything about that?

Given the restrictions and constraints of the pandemic, we agreed that we would go with a photosynthesis work because we felt that, within the time scales and the uncertainty, it was something we could deliver on. But we are in a new place and responding to the site and working with both seeds of European descent and some species of native seeds. It was important for us that we were not only using a European mix, and it’s exciting to see how these seeds differ as for the site: the Art Gallery of New South Wales and The Cutaway, where we’re exhibiting our work is on Gadigal land.

This interested us straight away because Gadigal land was a new term for us. Before Cooke and the British arrived, 29 clans occupied Sydney and the outer-Sydney region here. Around Dawes Point and the Sydney Harbour bridge is Gadigal land, and this is where we photographed Uncle Charles (Chicka) Madden and his granddaughter, Lille Madden: both deeply inspiring people (Lille is an activist involved with the first Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth movement around climate change, SeedMOB, and is now acting as the First Nation’s director at Groundswell whilst Uncle Chicka is a widely respected Gadigal elder), who carry this story of oppression and land-grab. It’s very important to draw attention to these things: this land.

Australia has been occupied for around 60,000 years, the oldest culture globally. Yet, since the arrival of the British – the colonisers – there has been massive degradation of the environment and massacres of the original inhabitants of the land, the Aboriginal first people. Just after we arrived in Sydney, we took part in Invasion Day or Australia Day as it is commonly celebrated. There is a shift happening; thousands took to the street with the chant “Always was. Always will be Aboriginal Land.”

What is the chief enemy of creativity?

Many of our projects are physically and emotionally demanding. It’s the nature of the work, and we keep remembering that when we feel up against it. Working with living plant material in new sites or more extreme temperatures can cause issues that may suddenly capsize our schedule. We have a broad wingspan of what we do, yet we sometimes feel over-extended. But this is classic. When you talk to people who have a small company or the like, you find they’re doing everything. We have people who can step in and help us. It’s not a moan, just a recognition that the admin and managing stuff sometimes seems to be taking over. We will feel inevitably pressured, and that artistic creativity is suffering.

You couldn’t live without…

Heather: I think if I ever lost my appetite for life, my curiosity or my sense of wonder. I couldn’t live without that natural sense of wonder. Particularly as the situation around the planetary crisis becomes direr and the warnings and science become more manifest and visceral.

Dan: There are so many things I think I couldn’t live without, but I would say the wildness of nature and woods and wine.

So: wonder, wine and woods.