Text by CLOT Magazine

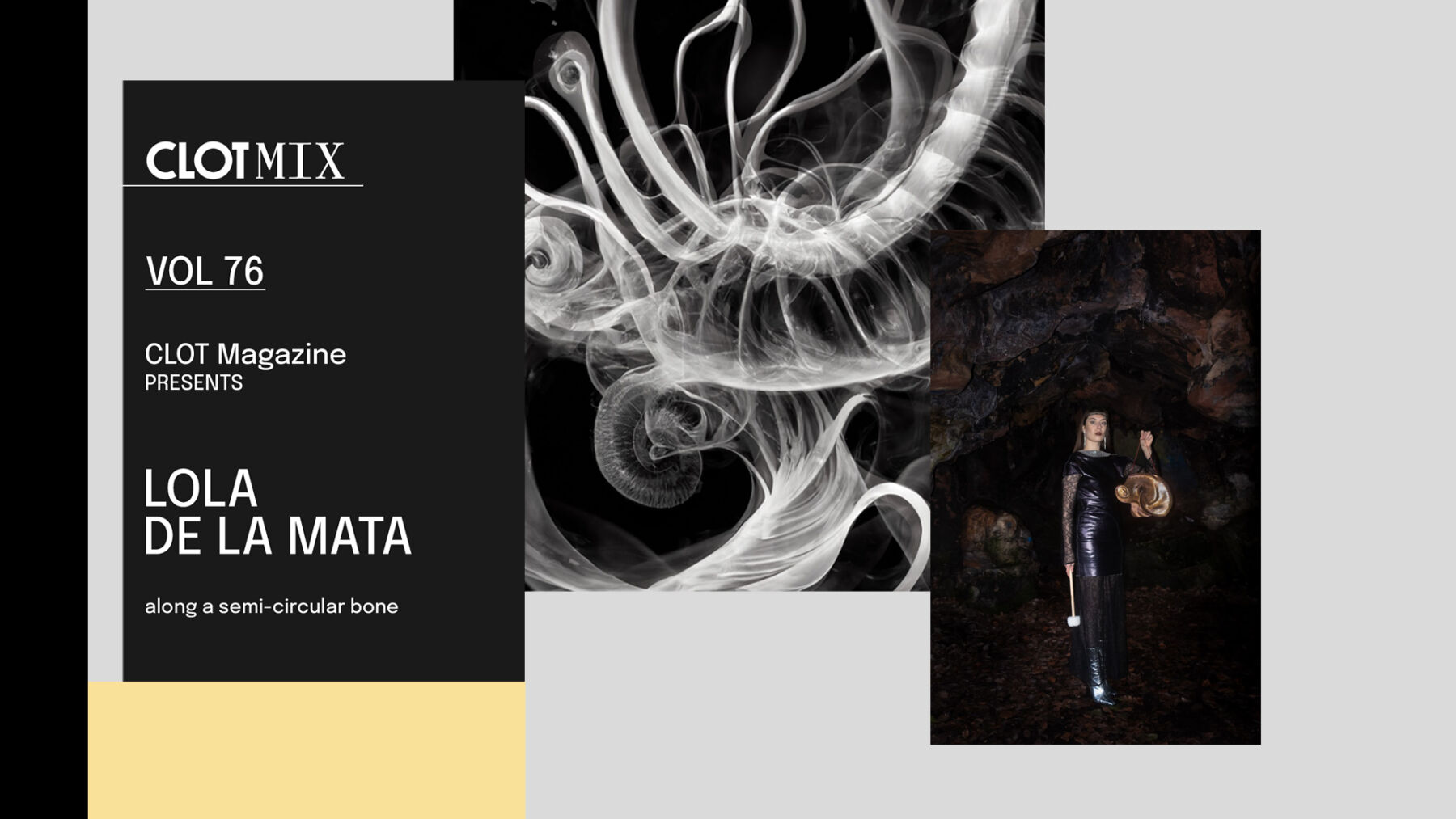

Introducing the latest auditory journey curated by Lola de la Mata for CLOT Magazine’s mixtape series. Delving into the mysterious realms of sound, the experimental composer presents a meticulously crafted selection of tracks that traverse the boundless landscapes of sonic exploration.

Lola de la Mata, a London-born French/Spanish conceptual sound artist, composer, curator, and musician (violin/voice/theremin), boasts a diverse practice spanning performance art, installation, community projects, and electroacoustic composition.

Her first release, the feminist concept album REMISE EN BOUCHE (Pan y Rosas Discos 2018), was followed by The Embalmer (Nonclassical 2021) and KOH—Klee—uh (SA Recordings 2022), laying the groundwork for her debut LP, Oceans on Azimuth, which is set for release on May 8th.

Currently, Lola’s artistic focus revolves around listening and hearing practices, tinnitus and aural diversity, and chronic illness experiences, something she centred on after experiencing a trauma episode herself. Rather than giving up music after developing severe tinnitus and vertigo, as she was told, she decided to listen with a new ear and dive deep into the world of tinnitus to cope with the isolating condition and facilitate the connection between sufferers.

For Oceans on Azimuth, she reached out to A.J. Hudspeth in New York who runs the sensory cell lab where they study the cochlea. There, she found collaborators in biophysicists who offered her the unique experience of recording her tinnitus.

Drawing inspiration from the intricate forms of the cochlea and the inner ear, Lola’s compositions emerge as avant-garde sonic tapestries, woven from the rhythmic pulsations of heartbeats and the ethereal whispers of tinnitus, transmuted through an array of innovative instruments. Metal, glass, ceramic, and ice converge to birth otherworldly timbres, while field recordings and traditional string instruments intertwine with inventions like the Claravox theremin and an ear canal-shaped gong.

On the other hand, the artist’s influence also extends far beyond the realm of composition. As a multifaceted artist, curator, and musician, her tireless advocacy for inclusivity and representation reverberates through her work. From collaborations with fellow artists (musicians, dancers and queer performance artists, most recently with Eve Stainton to a PhD pursuit in tinnitus research.

For this mix, she mentions: I treated the mix as a sonic collection of some of the artists I met and who inspired me along my project journey. With the exception of AYA and Tomoko Sauvage, whom I haven’t (yet?) had the chance to meet, some were chance meetings. Stephan Crasneanscki, founder of Soundwalk Collective and Maria Chávez at Rewire last year, for bagpipe player and composer Lise Barkas and I, it was mutual curiosity sitting by the Niki de Saint Phalle fountain outside IRCAM in Paris; while others such as Kepla are supporters of me and my work, and in Mira Calix’s case, whom this record is dedicated to, she adopted me as her mentee for two years before she passed. The other dedication on the record is to Anneka Swann – a friend who will retain part of my soul…with May 8th, the album release date marking one year since I last held her. Just as sombreness infused with respite flows through my body and left ear. The mix is imbued with grief, reflection and recalibration.

Oceans on Azimuth launch event is taking place on May 15th at The Stephen Lawrence Gallery in London.

Your album Oceans on Azimuth is an avant-garde, auditory odyssey into tinnitus. The project explores different forms of hearing and listening. Could you share what your creative process was like for the album production?

It was a slow unravelling and refocusing process from the body out. For almost three years, my entire attention has been captured by my ear and its incessant humming…screeching…thunderous clanging…, and tonal fogs.

Tuning my body to the ear was step one. Step two was finding a way of harvesting/holding/getting into the ear and looking around its architecture. Learning about its different components and chambers. It became my muse. I extracted my sound palette from the different elements present along the listening journey, following the waveform in air, then membranous flesh, bone, fluid, nerves firing electrical impulses, and finally into grey (soft) matter – then back out the way it came.

Step three was surrounding myself with people who knew more than I did about the cochlea. I wasn’t sure what form exactly the record would take at this point, it evolved rather organically when I reached out to biophysicists Jim Hudspeth and Francesco Gianoli, and musicologist Lana Norris from the Hudspeth sensory cell lab in NYC, who specialise in spontaneous otoacoustic emissions (SOAEs) and hair cell research.

Our common fascination with Marianne Amacher’s music locked us in step. I also worked with two cymbal/gong makers in Bristol from a mould of my ear canal and created samples from recording sessions with double bassists Gwendolyn Reed and Marianne Schofield, where we improvised around texts I had written and movements I had choreographed.

Your new compositions feature sonic landscapes crafted from throbbing heartbeats, and tinnitus phantoms reimagined through metal, glass, ceramic and ice musical instruments. Inspired by forms from the middle and inner ear, these prototypes introduced unique timbres and tonalities enriched with noise from their carved imperfections. Could you give us more details on how you developed these ear prototypes and how you translated the different timber and tonalities you ended up with into your own experiences and feelings for the album compositions?

It all started with an innocent moulding of my ear canals to be fitted with musician earplugs. From there, it descended into streams of experiments. The initial plan with the enlarged 3D printed left ear canal was to make ocarinas…which turned to dreams of bagpipes. Still, I got sidetracked when I met gong, cymbal and triangle maker Matt Nolan (who has made instruments for Bjork and Evelyn Glennie, no less!). The ocarinas and bagpipes are still in development btw – but my focus then was on metal, glass and ceramics. I had started working with glass on a previous project, ‘Nulla 0, a monolith’, and wanted to explore this further.

I was obsessed with the idea that we had two locked bodies of water, two oceans – one on each side of our head housed in each of our cochlea. Earlier in my research I had come across Ernst Haeckel’s beautiful illustrations of biology and had become instantly fascinated with deep sea silica creatures – radiolaria. Mesmerised by their forms, I pictured our head oceans populated by these, which led to the development of the large lace-like glass cymbals.

These produced incredible metallic clangs when softly tapped by fingers. Anything less fleshy and the intensity of the vibration cause the glass to snap. As you can probably tell by now, the record was developed by improvising with these prototypes and assembling and sculpting with samples until I felt I reached a form which expressed the essence of the concepts driven by literature around aural diversity through conversations at the laboratory and formed through texts I had written about my tinnitus.

In 2019, you experienced severe tinnitus and vertigo. Beyond the most evident effects, how has this impacted your approach to sound and music composition?

As you mentioned, I experienced an ear trauma when a loudspeaker emitted feedback while I was sitting beside it at a restaurant. My left ear and I didn’t have enough reaction time to prevent damage. Following this event were a couple of years of battling intense vertigo, migraines, and visual disturbances that rendered me bed-bound most of the time. Some days my speech and general cognition were affected, other days I was swallowed by fatigue. It meant I developed a slower practice.

My compositions were built in short bursts around the sampling, listening and arranging processes across many months. Often I would carve out a couple intensive days recording in a studio with all my instruments and sculptures, to use at a later point across different compositions. On this project, I worked with recording engineer Eve Morris (now at AIR studios), who completely put me at ease and really encouraged me to play. She placed microphones all over the room so that I could play with resonance and richness. The macro of the instrument, its materials vs spacial reflections.

I would say the space between the recording and the making is the most in-depth and time-consuming part of my practice. This time is dedicated to researching, thinking, and dreaming up precise concepts and characters for each piece. Only when I feel it has a sort of form, a sort of solidness to it, do I listen to the instrument samples I have chosen to group in order to compose. The composition then manifests rapidly. It’s probably this approach that makes my music feel intense.

You mention you are also a curator; in your curatorial practice, you emphasise working on projects which centre on women, non-binary and queer artists. How do you incorporate this focus when approaching this aspect of your practice? And what are the main challenges you face?

Well, I would be lying if I said I wasn’t made to feel uncomfortable or have had my presence questioned in various rehearsal and studio contexts. I also know I am not alone in feeling this way, so I aim to develop projects and work environments for myself and collaborators where the dynamics of the straight male gaze are lesser or not at all present so that we might all just get on and do our jobs.

I’ll try to answer your actual question now…as we know, there tends to be a gender imbalance in certain parts of the music industry. Mixing and mastering engineers and double bassists are expertise where most of the general public might casually assume there are no women in such roles. So it seemed like a clear choice to seek out such individuals to collaborate with on my project. (Shout-out to Cicely Balston at AIR studio, who did an incredible job cutting my record!)

What is your relationship with technology and analogue for your productions? And How do you cope with technology (screen/digital) overload?

I am pretty big on archiving and digitising (I worked for over three years digitising a film archive). I feel rather confident working fluidly between the two. Each has a clear role for me. Almost all the instruments are acoustic or analogue. All my notes are ink on paper – but the composing takes place exclusively using software. Partially out of comfort, all my printed textiles (what I initially trained in) would start as sketches/drawings and photographs and would evolve into a digital canvas. Most importantly, though – it’s out of a need to listen. I love the immediacy of playback, you are inside the sound, splicing it pixel by pixel – its great fun. Perhaps I am still enacting my role as a textile designer when making my musical compositions.