Text by Katažyna Jankovska

Understanding of time depends on what is valued in time. Capitalism sustains itself on ideas of the future and the perpetual movement forward. Looking through the lens of progress, the future is a continuation of the stable reality with the deep assumption that things will get better, “whether that be better technology, better politics, better inclusion, or better lives”[1]. Yet the question arises, better to whom? Moving to a “better future” keeps paving the way to ecological destruction, assuring that the future is even more exploitable. Slow environmental degradation occurs gradually and is out of sight. Yet again, out of sight to whom?

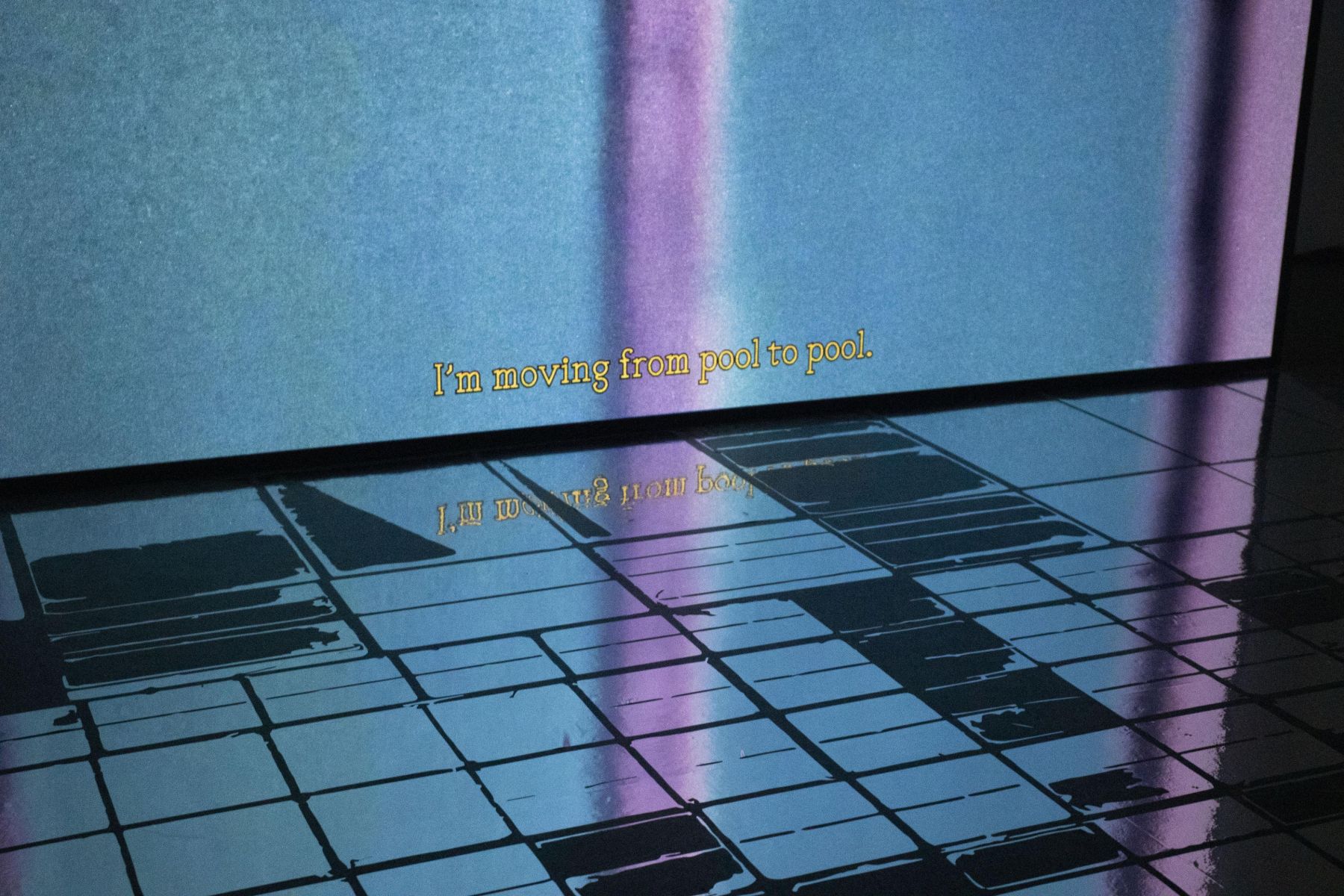

This edition of the Sonic Act Biennial in Amsterdam takes us on a journey between different temporalities. While the dominant order depends on fantasies of the future, the exhibition One Sun After Another at W193, Zone2Source, and Het HEM frames time from different standpoints. The storytellers embody a variety of guises, stretching time in ways that are non-linear, speeding up and slowing down the time frames. They are filling gaps in our perception of time with the nonhuman ways of witnessing time while manoeuvring between feelings of nostalgia, hope, and apprehension.

Our current relationship with the nonhuman world and environments is often represented through the lens of trauma. Although in our conventional understanding of time, one thing leads to another, geo-trauma has a peculiar relation to time. Rather than being traced back to a single event, it is represented by the gradual accumulation and complicated by the phenomenon of delay. The cause of the geo-trauma is usually difficult to locate, as the temporal gap between actions and repercussions makes consequences of violence gradually untied from its causes [2]. And when we move forward away from the past, it appears as a ghost demanding accountability for past actions and is not willing to disappear[3]. And so trauma spans generations.

So how can we make sense of the long-form disasters and delayed repercussions of our actions? Where do we look for the evidence? Some of them have no visual status. Since the gradual deterioration of the environment is beyond human-scale sensorium, artistic works invite us to use and retrain our senses. Toxins, for instance, are just substances until they interact with something that is eventually being harmed. Thousands of synthetic chemicals are present beyond the point of our perception. And the duration of exposure to the toxins makes them even more imperceptible.

Certain chemicals and toxins have strong odours that warn us about the danger. Although gas, which has a very distinctive smell, was odourless less than a hundred years ago[4]. The artificial scent added to the gas was supposed to alert us and prevent us from getting used to it. And yet we are gradually getting used to artificial odours that keep penetrating our spaces. With the introduction of fresh-smelling cleaning products, the scent of cleanness has become a standard.

In The Syntax of Smell, Cesar Majorana engages with scent-based memories making us realise how many of them are related to artificial scents. We gradually get inattentive to them. Leanne Wijnsma, on the other hand, reflects on the hyper-hygienic society by presenting three organic fragrances. Since the body odour comes from bacteria, A Wildlife presented in antibacterial gel pumps explores human instinctive feelings by manipulating the human microbiome.

The muddy, earthy, microbial scents affect our dopamine levels and can increase our chances of attracting or feeling attracted. To this day, the microbiome influenced how we evolved, but how can it help us evolve? And how scent-masking will influence our evolutional trajectories?

Certain traces of our actions appear in form of absence. The degradation of a sound environment brings us back to times when our planet lacked communicative sounds. At the very beginning, the Earth was completely different in terms of acoustics. Caused by the fear of listening to predators, for millions of years, there were no singing birds, croaking frogs, or whistling insects [5]. Nowadays, it’s man-made noise that interferes with the use of sound in animal communication.

Félix Blume’s work Swarm invites attuning to the sonic world of the nonhuman. The work is composed of 250 speakers hanging from the ceiling. Each speaker reproduces a sound of a flying bee, which together form the sound of the whole swarm. Recorded in constructed, acoustically isolated recording studio for bees, the work reproduces the buzz of a single bee and creates an immersive sound effect. Feeling hundreds of bees buzzing around, we are exercising our ability to listen to ecosystems that have been silenced.

Speed has been recognized as a key “toxic blind spot”[6] when it comes to environmental destruction. Yet sometimes, the accelerated perception of different timescales is needed to comprehend the slowly unfolding catastrophes. Especially when it comes to distant locations that are not that easily seen. A three-channel sound and video installation Gauge with footage and field recordings from the remote glacial regions filmed on Baffin Island by Danny Osborne, Patrick Thompson, Alexa Hatanaka, Sarah McNair-Landry, Eric McNair-Landry, Erik Boomer, and Raven Chacon plays with the natural forces of time. A time-lapse video of the graffiti emerging and disappearing on ice walls with the rise and fall of tides appears as documentation of temporary site-specific work. Time erases the ice murals, which melt away together with remote histories.

Another approach to speeding up time is seen in the work by Seline Buttner. Meiospore consists of little carpets and digitised moss projections reacting to human movement. The lack of roots makes moss reliant on nutrients from the atmosphere. Notable for their bioindicator characteristics, moss sensitivity can be used to rapidly detect and monitor air pollutants. They absorb what’s in the air, including pollution. In Meiospore, the ground overgrows with moss when standing or sitting still but immediately disappears when sensing human steps. The slow, invisible destruction is accelerated by the instant response to human actions.

Once absorbed, man-made chemicals and toxins remain for a long time in the soil, travelling from the underground into living organisms and continuously passing from one form to another. Such a witness constantly taking new forms appears in Andrea Galano’s work. A video installation De allá pa acá tells a story from a perspective of a traveling microbe, coming from the Atacama Desert to the computer battery.

Since certain microbes can survive in lithium once extracted, this nonhuman agent bears witness to events coming from the cosmos and carrying with it particles of meteorites, touching the ground of the Earth, laying underground, collecting different bodies on the way, and eventually being extracted and trapped inside of the lithium battery powering our computers.

In Pacific Fiction – Study for Monument by Julian Charrière, radioactive elements are “trapped” within the real coconuts. A pile of coconuts enclosed in the lead contains radiation and preserves the consequences of nuclear tests run by the United States government on the Marshall Islands. Together with the work Eneman III and Enyu I – almost idyllic photographs with radioactive exposure showing the abandoned and to this day contaminated island – the artist proves that the invisible elements such as toxins, pollutants, and radiation will be the biggest monument left by humanity, lasting millions of years deep beneath the earth, inside of living organisms, and mutating from one form to another.

Together with invisible elements left by humans across planetary scales, there will be ruins and remains of built infrastructures, surpassing human timescales. Today there are already tens of thousands of orphaned oil wells across the world. In OBIT, Sam Lavigne and Maryam Monalisa Gharavi collect names and dates of all abandoned oil wells in the United States. Next to that, they compile Oil News documents from 1989 to 2020 in chronological order. The collection of information that was rather supposed to be invisible, as the artists say, “points to that totality that was never meant to be totalized”[7].

The cyclical nature of trauma goes from human to environment and comes back to human. Although One Sun After Another points at the ecological trauma, its scars and its ruins, it, in a way, also suggests the intention of healing.

The audio-visual installation Hard Drives from Space by Louis Braddock Clarke and Zuzanna Zgierska documents the research focusing on the meteorite that landed in present-day Haviggivik, Greenland, and found its place in museums in New York and Copenhagen. While revealing the stories of exploitation and mineral extraction, this work steps outside of the linear.

Through the series of decolonizing rituals, stones are dissolved, remagnetised, and heated to the point that their magnetic information is erased. In the off-and-online guided meditation for Trans* and disabled futures Presence-past presence-present present-future by MELT (Ren Loren Britton & Isabel Paehr), artists manifest futures counter to heteronormative ways of being in time. And so we glimpse at futures yet to come.

Simultaneously accepting the haunting ghosts of the past, attuning to nonhuman temporalities, rewriting histories, and playing back time. Since the way we experience time influences the way in which we enact coming futures, whose experience of time will count?