Interview by Alessandra Coretti

Xiaodong Ma is an artist and hybrid designer whose creative identity expands at a symbiotic pace in different operating fields, from visual art to industrial and speculative design.

His work embodies a poetic, vulnerable, and sustainable contemporary narrative. Currently a senior industrial designer at SRAM (Chicago), Xiaodong Ma has received numerous awards for supporting his avant-garde design vision.

Fascinated by the intrinsic performative qualities of matter, the expressive potential of natural forms, and nature’s constant transformative/evolutionary motion, Xiaodong Ma’s works create deep spaces for reflection. In these spaces, the fragility of forms evokes beauty, recycling becomes a life philosophy, and objects transcend their finite status to become tools that interrogate personal and collective memories. These objects acquire new value through each repair, reshaping the paradigms of human interpersonal relationships and evoking a new sense of belonging and longevity.

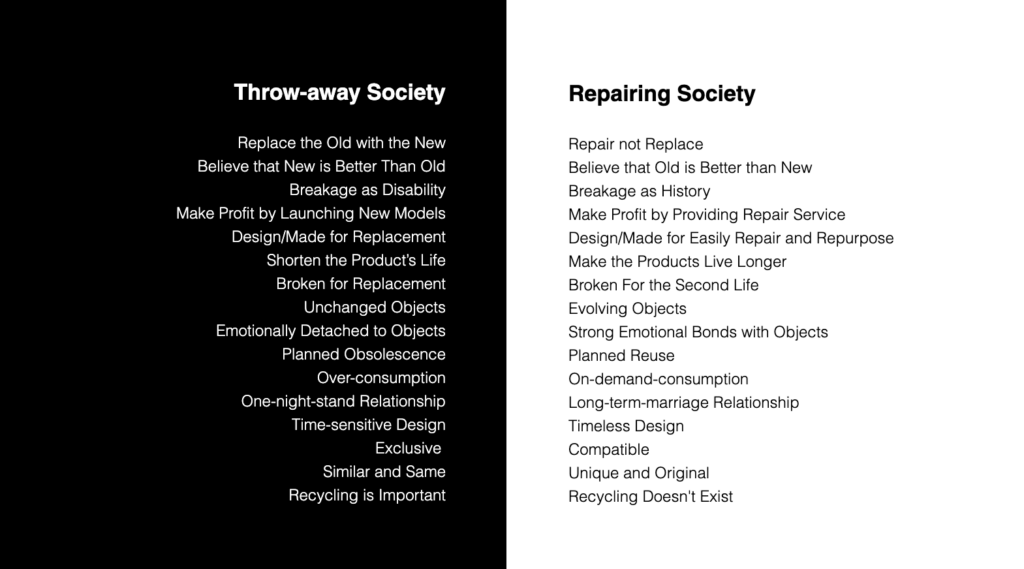

Repairing Society: A Nostalgia Future, for example, explores one of our society’s key aspects: Programmed Obsolescence. This work investigates the bulimic vortex that has overwhelmed our consumption habits and how much this has generated an impact at different heights – therefore, not only at an environmental level but also capable of orienting the desires of the society in which we are living, going to the point of corroding and weakening the perception of bonds and the way we live them. The work also endeavours to create the foundations for elaborating an ethical framework on the topic, questioning consumers, designers, and brands.

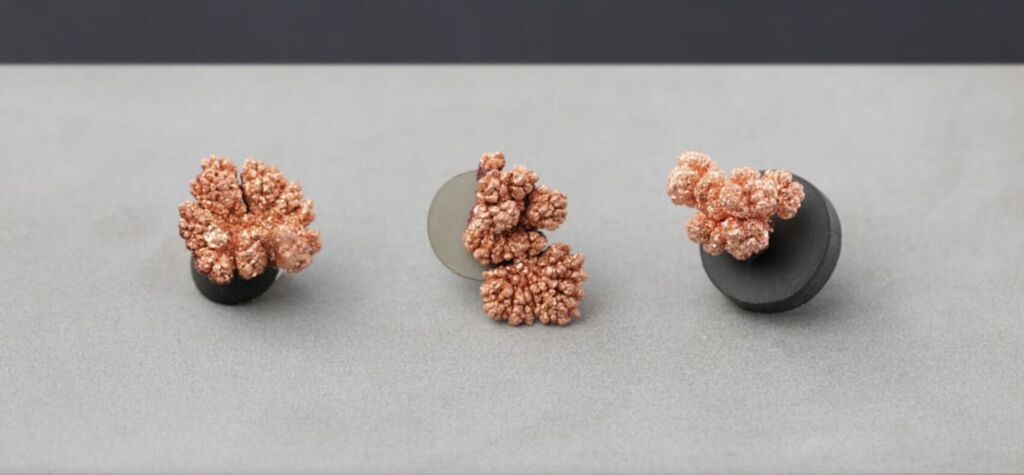

In 2e- Copper Electrolysis Collection, the artist investigates the aesthetic potential of waste through introspective material exploration. Specifically, the work is not concretely projected and created; rather, it emerges via the process of copper electrolysis, giving rise to elegant and essential jewellery. In this tendency to work from the inside, to intervene in the basic compositions of materials, to break down and recompose addends, one can also identify one of the fundamental traits of the expressive poetics in which the designer identifies himself: deconstructionism. This aspect is not only found in the tendency to deconstruct and recombine objects and materials to rewrite their uses but also in seeking a new meaning through in-depth work, excavation and experimentation of the material to reach its essence.

The artist/designer’s approach would thus seem to be an exploration focused on identity and internal geometries, not just epidermal and spatial ones. Although in the opposite aesthetic direction, the same vocation of excavation and deconstruction can be found in previous works that Xiaodong Ma has developed from his academic training years onwards, such as Reformation: Colour Melody in which phosphorous was used on a dark background, which in contact with a platform generated lines of colour that move and expand in synchrony with the sound vibrations.

Xiaodong Ma’s works shift visual planes through spatial dislocations, perceptual games, dismemberment of forms and reorganisation of objects. He proposes a new perspective on our present, challenging our sensory and cognitive habits, inviting us to question our current lifestyle, to be surprised by unexplored potential, and to reconsider the power of nature as one of the world’s most powerful expressions of art.

Your professional biography labels you as an industrial designer and visual artist. The two operating fields may share specific praxis, such as planning, experimentation, and creative thinking. However, they follow opposite paths for the outcome. Industrial design is inscribed in a functional horizon: solving a problem, satisfying a need, and focusing on the reproducibility of the object through the proof of concept. Art, instead, doesn’t want to be useful; it aims to problematize the experience to widen the lens of analysis by focusing on the uniqueness of the approach to an event or an object. How do you keep these two tensions in balance?

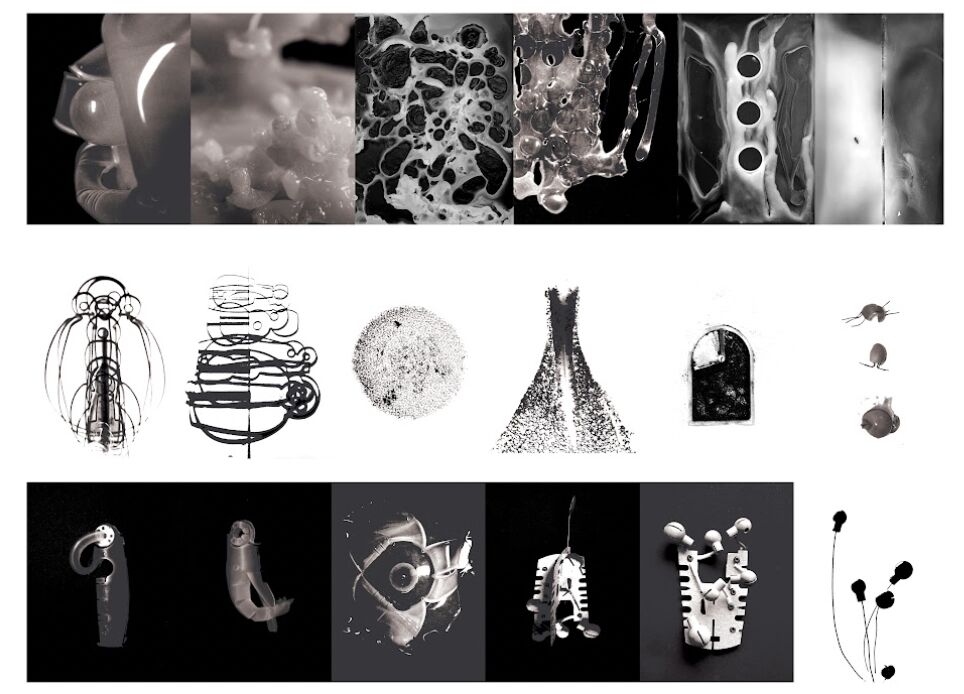

Initially uncertain about juggling Industrial Design and Visual Art, I found their symbiotic relationship profoundly enriching. Integrating both disciplines, I discovered a heightened creative confidence. Take, for instance, my artwork Reformation: Shadow Evolution, completed incidentally during the paper modelling process of a commercial design project. While making paper mockups for industrial design, I was captivated by the positive and negative spaces created by the paper models under light. This led to creating a shadow-related visual piece, blurring the boundaries between spaces and using three-dimensional objects to create black-and-white, two-dimensional effects.

In your opinion, are there common parameters between the two domains? How does your professional responsibility change depending on your role?

For me, the creative processes of visual art and industrial design are essentially about making things. The only difference is that visual art tends to be more about subjective self-expression, while industrial design aims to meet most people’s needs objectively. In both fields, I embrace the ethos of ‘What if … not …?’ and ‘Thinking by Making,’ challenging conventions and questioning life’s norms. This approach sparks unconventional ideas and fresh inspiration.

Were there any cultural or countercultural movements that particularly shaped your artistic vision? As an artist, which aspects of contemporary society and the collective image would you like to interact with and leave a trace of yourself?

My work as an artist can be categorized into Visual Art and Speculative Design. My Visual Art focuses on the transformation between dimensions. This obsession with spatial illusion stems from deconstructionism and my background as an industrial designer.

Firstly, I am particularly fond of how deconstructionism challenges and reconstructs existing forms and spaces, offering a new understanding of familiar things by breaking and reorganizing them. This challenges the audience’s sensory and cognitive habits. Its broad influence extends to architecture, art, fashion, and design. A representative visual artist, such as Picasso, created Bull in 1945.

Picasso begins by creating a realistic image of a bull. Then he deconstructs the bull, one step at a time, until what is left is a simple-looking sketch that represents the pure essence of the animal, a two-dimensional image composed of simple curves.

Still, it also retains the dynamics of the bull in three-dimensional space. On the other hand, part of my work as an industrial designer involves studying space and form, so my experiences in industrial design and deconstructing space in visual art often inspire each other.

Another category of my art is speculative design. Speculative design is an approach in design that explores potential futures by creating artefacts, scenarios, and narratives that provoke thought, discussion, and reflection on current social, cultural, and technological trends.

Reflecting on social issues brought about by consumerism is the central theme of my speculative design. Ironically, as an industrial designer, I am a beneficiary of consumerism, where people’s market-driven desires fuel the rise of countless brands and the impetus for product development iterations. However, as an artist, I am deeply concerned about the waste pollution and fleeting emotional bonds between people and objects brought about by consumerism and planned obsolescence. I want to express my views on this social topic through visual language.

For example, my thesis work in 2018-2019, Repairing Society, A Nostalgia Future, is a speculative design practice that addresses the consumerist perception that ‘new is better than old’ and fosters a solid attachment between users and objects. In this project, I imagined a society opposing our current ‘throw-away’ society by proposing three solutions and scenarios (Repair, Graft, and Autotomy).

Your working method conveys a deep fascination with the expressive possibilities of natural material, its internal structures and forms, and how they dialogue with other factors such as light, shadows and sound. How does this interest come about? How do you think digital technologies can support and expand your creative aims?

I’m glad you noticed that. Yes, I am very passionate about natural forms. As we observe our environment, we realize that two main types of forms surround us: man-made and natural. We lose track of this context, maybe because of our life rhythm or because we are too immersed in our man-made world. Man-made forms are generally ‘completely controllable forms,’ such as plastic parts mass-produced by injection moulding, where each piece is identical. On the other hand, natural forms result from variables and interference, making them unpredictable. What is fascinating about nature is that it is ever-changing.

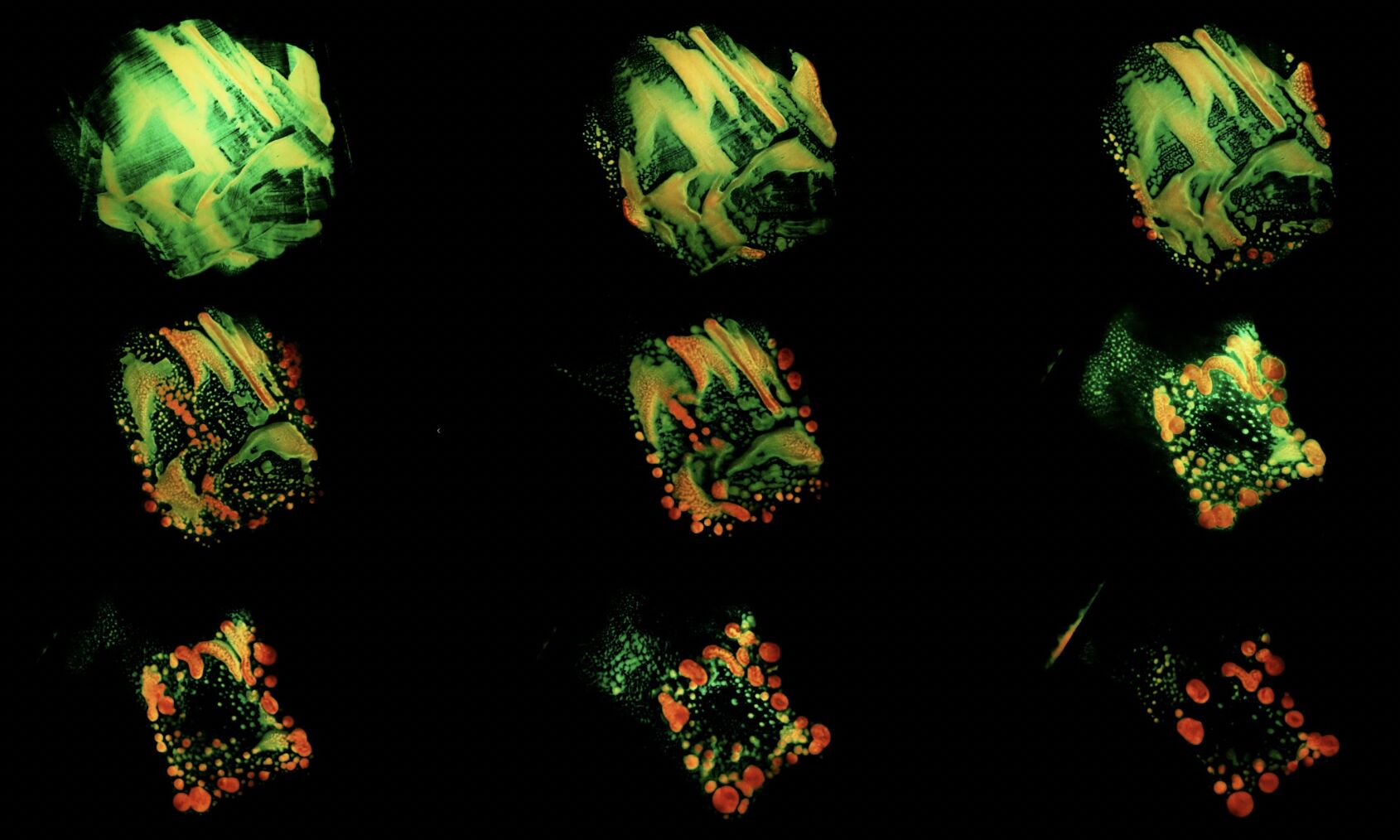

For example, in my work Reformation: Color Melody, I put phosphor on a speaker platform in a blacklight environment, such that the phosphor represented the rich layers of colours and textures with the rhythm of the music and the vibration of the sound. In this project, digital technology efficiently helped me capture unique forms in each moment of three-dimensional objects/spaces.

In one of your works, 2e- Copper Electrolysis Collection, which consists of copper jewellery, the performative side of the project is based on the introspective analysis of the material; the form of the work is not modelled but revealed through a process of electrolysis of the copper. This way of working on the essence of the material allows us to discover new artistic qualities of the work. It brings us closer to a primordial rhythmic scansion: the evolutionary rhythm of nature. Can you describe the stages of this work? Regarding experimentation and process, what kind of feedback have you received?

People perceive recycled products as sustainable designs that sacrifice some performance and appearance. To challenge this notion, I explored the potential beauty of industrial copper waste through electrolysis at the project’s outset. I chose jewellery as the medium because the stark contrast between industrial copper waste and the elegance of jewellery effectively prompts viewers to reconsider the immense reuse potential of industrial waste and encourages innovation in the material-recycling process.

My industrial design work inspired me to use electrolysis to recycle copper waste. Specifically, the electrolysis (electroplating) process commonly used in metal surface cleaning inspired me to wonder if electrolysis was used in metal forming instead of plating.

After four months of experimentation, I explored the diverse crystal forms of scrap copper by controlling the electrolysis process and manipulating various factors. Numerous factors can influence electrolysed copper’s form, durability, and finish color, such as current, voltage, sulfate solution concentration, and the distance and orientation of the anode and cathode.

Another project that stimulates reflection on several levels is Repairing Society: A Nostalgia Future. The work investigates the responsibilities of consumers, designers, and brands regarding the life cycle of objects and the respective concept of planned obsolescence. You propose a vision focused on the historical and symbolic value of the object, protected by the act of repairing instead of replacing, with objects that could re-establish a new value of non-replaceability to human bonds as well. Could you explain more about this work’s needs and how you developed it?

Repairing Society is a speculative design practice that challenges the consumerist notion that “new is better than old” and fosters a strong attachment between users and objects. In this project, I imagined a society that opposes our current throwaway culture by proposing three solutions and scenarios: Repair, Graft, and Autotomy.

This project showcases my accumulated experience as a designer, my interest in the emotional bonds between people and objects, and my rethinking of modern lifestyles. It includes design research on the history of consumerism and repair cultures in different countries and regions. It features service design and industrial design centred around the three themes of ‘REPAIR, GRAFT, AUTOTOMY’ and related stakeholders.

REPAIR: Broken is Better Than New

When I was a child, repair services were ubiquitous. Repairmen, such as tinkers, sharpeners, and shoe cobblers, wandered through streets and communities, offering their services. After their repair work, the items looked new. These artisans devoted their lives to prolonging the stories and strengthening the bonds between objects and their owners. In the Repairing Society, products are designed to last longer through repeated repairs, reviving traditional repair trades, creating more job opportunities, and empowering citizens to become repair people.

GRAFT: Recombining for Repurpose

Grafting, a horticultural technique in which plant tissues are joined to continue growing together, inspires this concept. In the Repairing Society, broken objects or parts can be recombined and converted into new products, extending their function and usability while preserving their original essence. This process allows owners to cultivate and deepen their bonds with these objects, signalling a history and capability for continual evolution and use.

AUTOTOMY: Design for Broken

Broken for Second Life is a design ethic for brands and designers in the Repairing Society. Objects are designed to break gracefully and cleanly, making future repairs and repurposing easier. Each repair adds to an object’s potential, history, soul, and inherent beauty. Designers focus on creating repairable items, considering not only how products are used but also how they will break. This ensures that an object’s afterlife is well-planned from the beginning, emphasizing a long arc of use and evolving appearance and meaning.

In summary, Repairing Society promotes a culture of repair and repurposing, aiming to transform our consumerist habits and foster a more sustainable, emotionally connected relationship with our belongings.

In Re-Formation Image-Object-Image/ Shadow-Revolution/ Color-Melody, one of your first visual artworks, you created a series of delicate experiments that express the transition between different dimensions in three distinct ways and with various materials. The project explores the stylization of forms and the decontextualization of the object. Could you tell us more about the research sphere around this series?

As mentioned above, deconstructionism plays a significant role in my art creation. The three works in the Reformation series are visual art pieces I created during my MFA at CCA based on my understanding of deconstruction. This series marks my first attempt at art creation from a traditional industrial design background. The three works—Image-Object-Image, Shadow-Revolution, and Color-Melody—aim to challenge the audience’s cognitive inertia by breaking down and reconstructing familiar everyday objects, spaces, and mediums.

Image-Object-Image (Deconstruction of Everyday Objects)

In this piece, I deliberately selected everyday objects and reimagined them by disassembling, editing, and recombining them into functional drawing tools capable of producing dots, lines, and intricate patterns. As I continued experimenting with and reconstructing these drawing tools, I simultaneously generated new experimental 2D drawings. With each iterative cycle, both the drawings and the tools evolved together. During this process, the 2D and 3D outcomes may have lost certain connections to their original forms. Still, they also gave birth to something entirely new, inviting the audience to reimagine the familiar.

Shadow-Revolution (Deconstruction of Space)

By questioning the boundaries of 2D and 3D, I reassembled paper forms and captured the evolving relationship between the objects and their shadows, generating a series of black-and-white, positive-and-negative patterns.

Color-Melody (Deconstruction of Medium)

To visualize sound, I applied phosphor to a speaker platform in a blacklight environment, allowing the phosphor to represent rich layers of colours and textures with the rhythm of the music.

What’s your chief enemy of creativity?

Perfectionism is the chief enemy of creativity. I used to be a perfectionist (and perhaps I still am). In my pursuit of perfection, I would sometimes delay finishing work because I always felt there was room for improvement. This procrastination can lead to projects not being completed on time and can hinder the generation and realization of new ideas.

One way I overcome this procrastination is by thinking by making. I imagine a near-term deadline (such as within a week) and then force myself to make something within that week. The quality of the result doesn’t matter; what matters is that I start doing something.

Additionally, perfectionism often puts too much pressure on me to achieve extremely high standards. This pressure can lead to anxiety and burnout, making it difficult for me to engage in creative thinking and activities. The solution is to constantly remind myself to “relax and enjoy the process.”

You couldn’t live without….

I couldn’t live without curiosity. Especially as an industrial designer and visual artist, curiosity drives me to continually explore new works and creative themes beyond my regular work.