Words by Lula Criado

Elaine Whittaker, a bioartist based in Toronto, Canada, uses a wide range of media such as sculpture, installation or digital images to create artworks that allow audiences to better understand science and scientific issues.

Working in the intersection of art, science and blending the organic: mosquitoes and bacteria with the inorganic: salt crystals or wax she explores the microscopic world making visible the invisible. Inspiring and thought-provoking are two of the words that define the creative universe of Elaine Whittaker’s art.

One of the central axes of her work is to challenge the viewers’ perception of bacteria and other living microorganisms to make them think about the social prejudices with regard to microbes and disease: living microorganisms are, on one side beneficial and necessary but, on the other side, they can make us sick.

A virus (in Latin refers to ‘poison’) is a microorganism smaller than a bacteria that only can grow and replicate itself in a living cell of another organism and is spread in many ways such as oral, sexual or exposure to fluid or infected blood.

With the ability to mutate in each infected person, a year of living amid the Ebola virus outbreak in West Africa has evidenced how vulnerable the human condition is. Following this two installations have caught my attention: I Caught at the Movies (2013) and Shiver (2015).

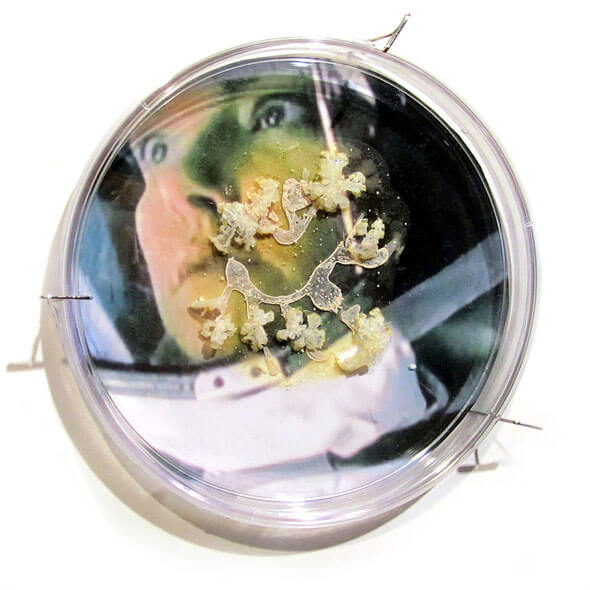

I Caught It at the Movies is a mixed-media installation of digital images, microorganisms and paintings that points out the social fear of contagion. On the other hand, Shiver —her last exhibition at The Read Head Gallery in Toronto— is an installation created from diverse materials such as salt crystals, Petri dishes, pipette tips and wool focused on challenging the perception in society about infection and viruses.

You are a visual artist working in the intersection of art and science, when and how did the fascination with biological systems come about?

As a young person, I was fascinated by the natural world. We lived in a small country town and my childhood was filled with playing outdoors in the surrounding meadows, creeks, forest, and flowing grass fields.

My activities with family and friends were often exciting explorations of these areas. I would keep a close eye on the progress of the anthill in my backyard, look for hummingbird nests in the hedges, dangle my feet in the creek so that minnows would tickle my toes or hike the escarpment and peer into every crevice in the hope of seeing a fox cub.

These interests were nurtured by my parents who brought home books on bird and insect identification, enrolled me in the Young Naturalists Club, and took me to Audubon Wildlife film nights. Though I did not go on to study biology or biological systems formally these interests continued throughout my postsecondary studies in anthropology and art and launched me to work in the environmental movement.

All these influences have found their way into my artistic practice. For example, the instigation for incorporating organic materials into my art comes from my investigation and research on toxicity and health. This led me to salt, a relatively simple material, and one of the oldest healing substances humans have adopted.

Salt is a mineral, and I mimicked the organic by growing and nurturing diaphanous crystals on created and found objects. The salted objects can be perceived by viewers as organic because the crystals have been grown. I was also drawn to salt because it is the foundation for life, from our primordial past in a briny ocean to our fetal beginnings in the salty milk of amniotic fluid.

Trespassing these boundaries between organic and inorganic, and between microscopic and macroscopic, salt became both my main material and metaphor in my artworks. It was around this time that I was invited to work with a developmental biologist and butoh performer to create a salt installation for the science, art and dance festival, Shared Habitat 2 (2002), and this collaboration furthered the intersections of my artwork with themes from science, particularly new developments in biology.

Incorporating live bacteria into my artwork started soon after this. I was researching and investigating the history of pandemics, the rise of infectious diseases brought on by global warming, and the natural history of microbial life on Earth.

With a research grant from the Canada Council for the Arts (2009), I took the first steps in setting up a laboratory in my studio and learned how to culture the salt bacteria Halobacterium sp. NRC-1. With a microscope and digital camera, I photographed the growth of these brightly coloured colonies and then used the images in installations, or displayed the actual petri dishes with halobacteria as live drawings. Over the past years, I have created a number of other installations employing halobacteria.

In the early 1920s, Cubism helped physicist Niels Bohr determine the quantum theory when he compared the behaviour of electrons with Cubist paintings. But what is the contribution of science to the arts?

My knowledge of this has recently been greatly expanded by reading Arthur I. Miller’s excellent new book, Colliding Worlds: How Cutting-edge Science is Redefining Contemporary Art (2014). Extensively researched, he provides many examples of artists that unite science and technology in their work.

For the book, he concentrated on artists that either illuminate science in their art via research, or work directly and collaborate with scientists. In the chapter, Imagining and Designing Life he looks at those artists who are influenced by biology writing, “Biology-influenced art was the next major Artsci movement to emerge after computer art…It has really hit its stride in the twenty-first century. Biology is the science of life.

Of all the sciences biology touches us all most immediately. While other science-influenced art movements can expand our horizons and inspire us, biology-influenced art has the potential actually to affect our lives” (p.189).

Some of the Bioartists he presents in this chapter include Marta de Menezes, Nina Sellars, Sterlac, Andrew Carnie, Orlan, Suzanne Anker, Joe Davis, and the team of Oran Catts and Ionat Zurr, to name a few. The contribution of biology to these artists, and to myself, is instrumental in enabling us to push the boundaries between art and science, providing a multi-dimensional framework to work with while adopting a range of new media and processes.

Is art helping understand scientific issues or it is challenging what society understands about them?

You just have to look at the blog ‘Symbiartic’ (the art of science and the science of art) on the Scientific American Blog Network written by the great team of Glendon Mellow, Kalliopi Monoyios and Katie McKissick to see that artists are creating artworks that both are challenging and enabling audiences to better understand science. In their blog, they highlight an amazing array of science illustrators and fine artists conveying scientific issues and processes in very thought-provoking ways.

What are your aims as a bioartist working in between science and art?

For the last number of years, my research and interests have centred on the porosity of the human body and the beauty of the microbes that inhabit its ecology. Working with the notion that microbes, the oldest forms of life on earth terrify us (an invisible invader with the possibility of contaminating our cellular lives, even though we host them on and in our bodies). I have been re-imagining what it means to be infected in contemporary society, examining how epidemics/pandemics evolve, and their cultural significance.

A past installation, entitled Ambient Plagues (2013), presented artworks exploring our fear of infectious disease. With this exhibit, I collapsed fiction and reality by displaying an array of pseudo-scientific objects, and images of people expressing fear found in ‘disease’ movies–the fantastical movie genre where viruses threaten to destroy human societies.

My most recent installation, Shiver (2015), continued to examine these fears, but with the microscopic body as a possible site of infection. Using the context of the current ebola epidemic as a backdrop, my mixed media artworks asked viewers to consider that fear and beauty reside in an uncomfortable dialectic.

In this precarious time of emerging contagions and impending pandemics, it seemed important to find a way to unpack and contest such discourses, especially given how they intersect with all the security and surveillance systems that corporations and states seem to be endlessly extending.

Do I create my artwork with intentional or specific aims? Not overtly. Instead, I hope that my artwork as a bioartist will open a dialogue with the viewer, moving them to question and re-examine their fears of microbes and infection and connect these to wider social and political issues in our society, while marvelling in wonderment at both the fragility and resilience of the human body.

If you could visit a scientist’s mind, who would it be and why?

Rachel Carson, the great path-breaker, ecologist and scientist. As she said in her book Silent Spring, “In nature, nothing exists alone.” Because she worked to connect her own scientific practice with the arts of everyday life. “We stand now where two roads diverge. But unlike the roads in Robert Frost’s familiar poem, they are not equally fair.

The road we have long been travelling is deceptively easy, a smooth superhighway on which we progress with great speed, but at its end lies disaster. The other fork of the road—the one less travelled by—offers our last our only chance to reach a destination that assures the preservation of the earth.” Because she said: “A who’s who of pesticides is therefore of concern to us all.

If we are going to live so intimately with these chemicals, eating and drinking them, taking them into the very marrow of our bones – we had better know something about their nature and their power.”

Because as a scientist and an ecologist, she overturned the way people look at the natural world. And for a woman at that point in time, she was fearless.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

Fear.

You couldn’t live without…

Dancing!

…and the ability to creatively look at life with wonderment and curiosity, and weave together ideas about where change in this world is possible.