Words by Cathrine Disney

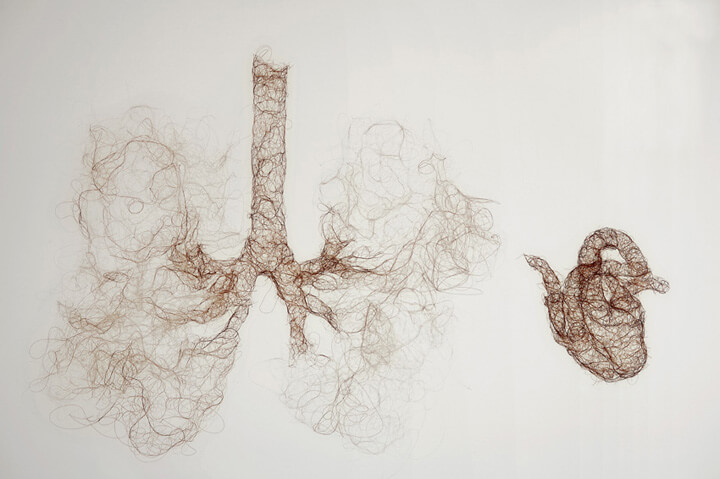

Visual artist Helen Pynor holds a Bachelor of Science, a Bachelor of Arts and a practice-based PhD resulting in truly cross-disciplinary collaborative practice. Pynor works in a variety of media, from sculpture, installation, performance and new media to photography and video and explores our bodies from the inside out, being one of the main aims of her work to decode the relationships between materiality and cultural constructs surrounding the human body.

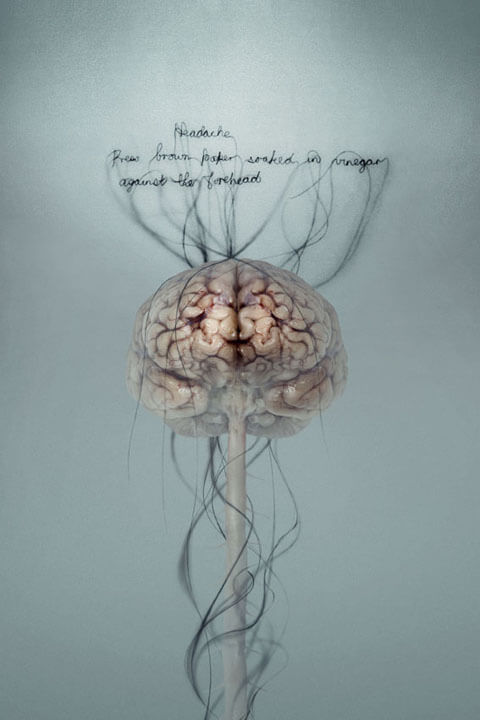

Pain, illness and its relationship with the human body is represented in her Red Sea Blue Water series, a collection of beautiful and striking photographs of floating and blurred organs and their pain and illness associated.

Head colds, backaches, earaches, tooth abscesses or headaches, to name just a few, are some of the organs, pains and illnesses described. Head Ache from this series became an iconic representative for the exhibition Brains: the Mind as Matter at Wellcome Collection in London in 2012 and at the Museum of Science and Industry in Manchester in 2013.

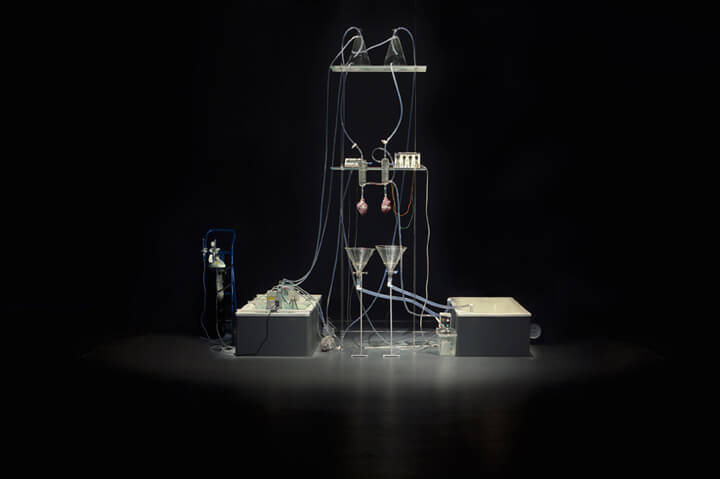

Her most recent artwork The Body is a Big Place, a collaborative bioart work with Peta Clancy, is an immersive installation itself which lies in the heart of organ transplantation and explores how fine the thin red line between death and life is.

The artists investigate the ambiguities of life and death through the notion of organ transplants. Rather than portraying death as a single moment, they demonstrate the concept as an extended process.

Through live performances the artists focus the viewer’s attention on the cultural and medical significance of organ transplantation: from death to life on one hand, and from donation to reception of the organ on the other one.

Helen Pynor explores the intersection of art and life sciences and by doing this she takes our hand in a journey in which the significance of our existence is not related to philosophical questions only any more. Her work is a somatic reflection of the inside human body.

The Body is a Big Place’, Helen Pynor and Peta Clancy (2011). Performance still. Photo credit: Geordie Cargill

You are an artist working in the intersection of art and science, when and how did the fascination with biological systems come about?

My fascination began early, growing up in a bush suburb of Sydney where the wildlife around me was rich and vivid. At home large blue-tongue lizards waddled into our yard, deliciously bright lorikeets and screeching cockatoos populated the skies, the rhythmic doof of cicadas and crickets began like clockwork at dusk, and I still have in a jar of methylated spirits the deadly black funnel web spider we found in the laundry one year.

I began collecting insects at a young age and designed elaborate cages for feeding and keeping them alive for long periods of time. At the age of seven, I decided to become an entomologist and after leaving school I completed a science degree in cell and molecular biology but before starting a PhD in the field I stalled with growing doubts.

I still loved the organisms that biologists studied but jobs in labs taught me that scientists were focused on tiny parts of biological subsystems, incisions into a larger complexity, and I doubted whether it would satisfy me.

In parallel, I was exploring a growing interest in art, at the time focused on photography and later moving into sculpture, installation and other media, and 4 years after finishing my science degree I was at art school full-time.

In the early 1920s, Cubism helped physicist Niels Bohr to determine the quantum theory when he compared the behaviour of electrons with Cubist paintings. But, in your view what is the contribution of science to the arts?

No comments.

Bioart lies between art and bioscience to explore laboratory practices as an artistic medium. Is bioart blurring the boundaries between scientific research and creative expressions to make scientific research more accessible to the public or is it challenging what society understands about it?

Bioart isn’t a single practice and doesn’t have a single purpose that would fit all artists working in the terrain. My aim is to make manifest some of the strange, wonderful, disturbing and life-affirming characteristics of living beings – human and non-human – and to help remind us that life is always stranger and more surprising than anything that could be corralled into our rationalist or reductionist knowledge systems.

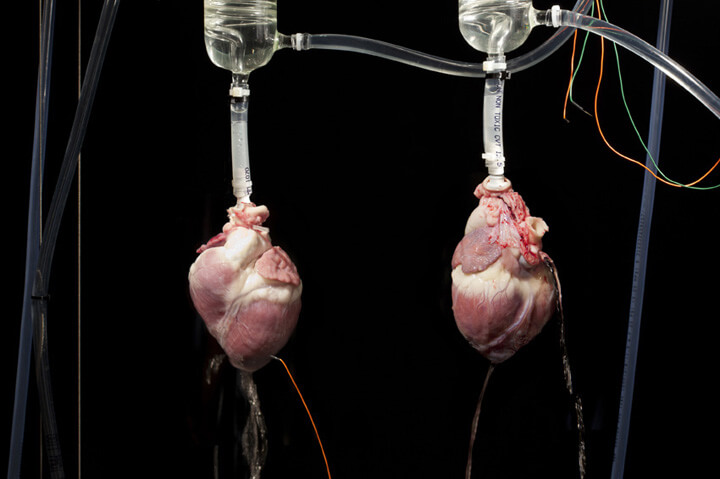

The Body is a Big Place is an installation including a perfusion performance in which living materials take part. For scientists one area of ethical concerns is how to dispose of the living tissue at the end of an experiment. What ethical/philosophical issues arise in the use of living systems for artistic proposals? How do you cope with the living tissue at the end of an exhibition?

Engaging with biological entities always inspires in me an ethics of care and responsibility, whether I’m dealing with organs that continue to function outside the body they came from or tiny cells growing in incubators and relying on me to provide nourishment and an environment where they can grow and function.

Whenever I can, I allow these entities to live on until they’re not capable of further life. However, processes like cell culture result in the regular culling and killing of cells each time the cells are reseeded into a new culture flask. I’ve always sourced the tissues for my work from animals who were being killed for some other purpose, mainly through abattoirs, and I’ve obtained organs as a by-product.

It’s been confronting and challenging to be on the ‘shop floor’ of abattoirs during the killing of animals, but it seems more honest to face what goes on to enable meat eating than avoid or deny this spectre, and through it I’ve developed a deeper respect for animal lives.

In some cases a strong bond forms and I feel compelled to ritualise the end of a life. For example, during the heart perfusion performance, I undertook with artist Peta Clancy and scientist Goradz Drevensek at Galerija Kapelica in Ljubljana, Slovenia, the two pig hearts we were perfusing continued to beat for 10 and 20 hours respectively.

We didn’t expect them to beat for so long and Peta and I slept on the gallery floor to watch over them during the night. The next night we all felt compelled to ritualise their burial so we drove them to the Ljubljansko Barje, a heritage moor outside of Ljubljana, and buried them in the damp earth under candlelight amidst a cacophony of frog song.

It was a process that sat somewhere between animist ritual and macabre bush gothic, somehow fitting for these entities that also drifted between categories.

What are your aims as a (bio)artist working in between scientific methodologies/techniques and art?

I’m fascinated by ambiguous zones that are difficult to articulate in languages, such as the life-death border or the interpersonal experiences of some organ transplant recipients. These terrains of experience raise complex philosophical questions that can’t be easily approached in medical or scientific terms.

Art has an important role to play here in raising and framing questions about the ineffable and providing sensory languages for approaching these questions.

In my work, I depend on the methodologies and expertise of scientists and clinicians but I have very different conceptual goals. Like art, science deals in the terrain of speculation, but its progress depends on offering provisional answers to incremental questions.

Medical practice looks for the kind of certainty that can guide those on the ground facing pragmatic decisions like, for example, whether to continue resuscitation of a cardiac arrest patient or the point at which it’s acceptable to remove organs for a donation from a beating heart cadaver.

These are compellingly complex questions but for medical practice to continue in its current form, a degree of certainty for clinicians and patients is needed. In the case of both science and medicine, certainty is sought even if it remains provisional or unattainable.

In my practice, I dive into the detail of these zones of uncertainty and tug at the threads of their unknowability. I take methodologies from science and re-contextualise them into other contexts where their meaning is radically changed.

I use these methodologies to pose questions rather than to answer them and in this way to explore and perpetuate a philosophy of uncertainty.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

Fear, although it’s also one of the most important friends of creativity. Administration and information overload.

You couldn’t live without…

Making art, the works of other artists, those nearest and dearest to me, Eucalypts and Angophoras, too many birds to mention…