Interview by Meritxell Rosell

“The immune system is a plan for meaningful action to construct and maintain the boundaries for what may count as self and other in the crucial realms of the normal and the pathological.”

Donna Haraway, Simians, Cyborgs and Women; The Reinvention of Nature (1991). The Biopolitics of Postmodern Bodies: Constitutions of Self in Immune System Discourse

Lynn Hershman Leeson is a pioneering figure in media art. Since the 1960s, the American artist has been creating works that address the interplay between technology, media, identity and the mutating relationship between the body and technology. She examines how new technological tools can impact our social life, ideas about individual identity, and our relationship with the real and virtual world using photography, film, video, computer-based art and performance.

Hershman Leeson began working with concepts around cyborgs as early as 1962 (we could say planting a fertile seed for Donna Haraway’s 1975 essay ‘A Cyborg Manifesto’)1. In the 1990s, she started working with the themes of artificial intelligence and virtual reality. A time when it became evident that it was no longer necessary to have a physical body to adopt a fictitious identity in the global network. She coined the term “anti-body” to refer to her research and work on virtual identity in cyberspace. She saw her “anti-body” (or alter-ego) as a viral presence in artificial intelligence fictitious forms, such as the online personas Agent Ruby and DiNA, roaming the Internet and morphing to survive. As she explains: anti-bodies identify, expose and transform toxins in culture. These same issues have permeated my work for the past 50 years.

Now Hershman Leeson has brought her work a step further -in what seems the culmination of her research- with a project rounding all this pioneering work with a major solo show, bringing together her latest work on biotechnological advancements, _Anti-Bodies_. The exhibition comes from the hand of HeK (House of Electronic Arts Basel)2, and central to it will be the final version of _The Infinity Engine _, a piece that raises questions about the ethics of DNA manipulation and its impact on society: how bioengineering is altering our concept of identity and human uniqueness.

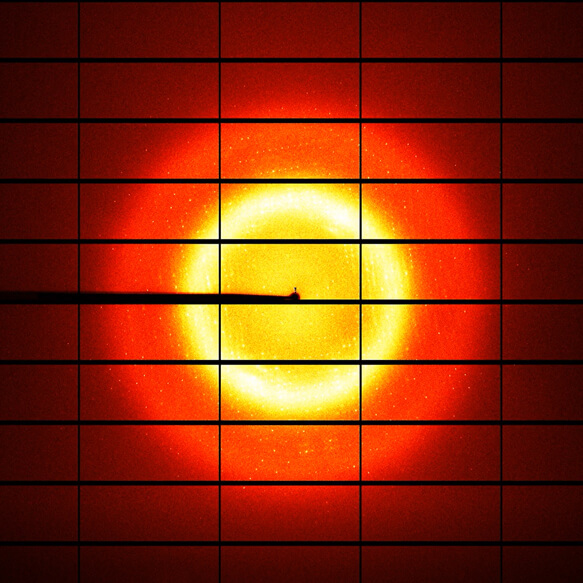

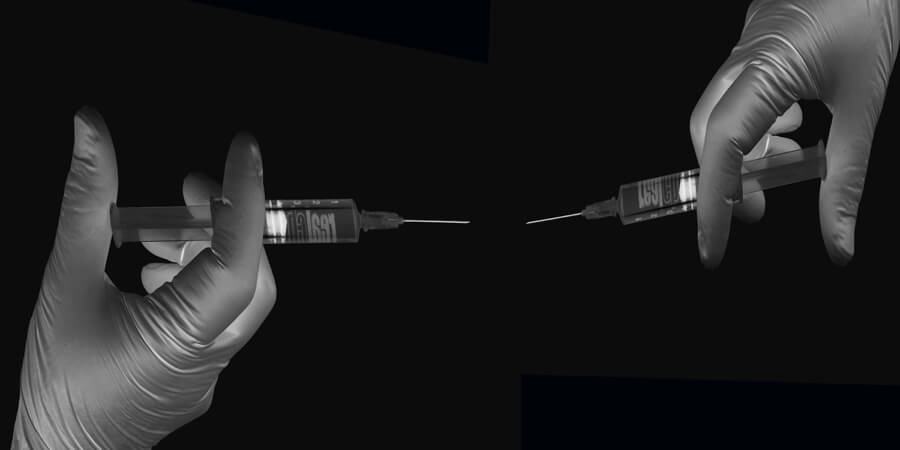

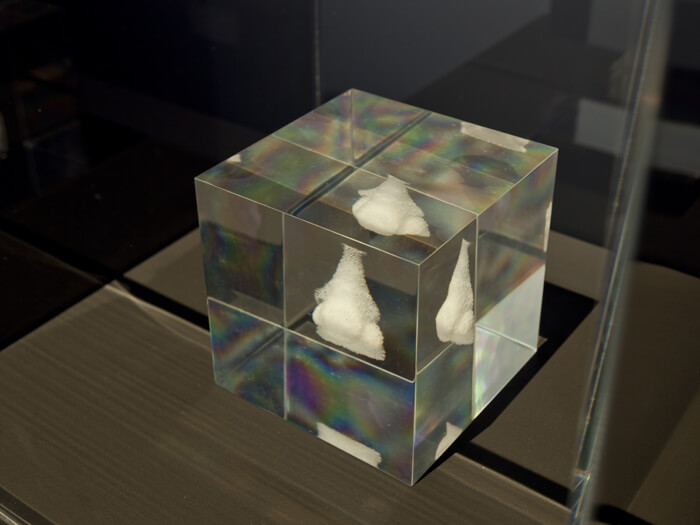

The piece will take the form of a composition of genetics labs with their unique signage and equipment, files of legal documents related to genetic engineering, and a facial recognition booth that identifies vital parts of the viewers’ identity. Most excitingly, it will also portray The Antibody Room, featuring the development of an artificially engineered antibody that bears the name “Lynn Hershman” in its molecular structure. A project was developed in collaboration with Novartis and inspired by today’s leading scientific research.

Besides their widely known role as immune molecules and vaccines, antibodies have become a central tool for biotechnology and biomedicine and are well-established therapeutic modalities in the Novartis portfolio. Hershman worked alongside Dr Thomas Huber (the therapeutic antibody research group leader in Novartis) to create this new antibody. And, as it’s standard in biotechnology laboratories after the antibody was designed, it was subjected to a series of research experiments to discover its properties and potential therapeutic or research applications. Still undergoing investigations, it will be interesting to know what molecule this antibody targets and whether it is involved in any disease or therapeutic pathway (some preliminary results will be revealed on April 24, Dr Huber shared with us).

With this latest work, Hershman Leeson gives a new biological dimension to the concept of “alter-egos” and what it means to be human. An antibody seems in her hands the ultra representation of identity in the form of a reactive molecule that can even be reactive against oneself. A representative example of the depiction of the technology-induced epistemological changes in art that started in the second half of the last century and have strongly crystallised at the turn of this one.

1 Early Cyborg artwork is currently being shown at Anglim Gilbert Gallery (San Francisco) and Waldburger Wouters (Brussels)

2 _Anti-Bodies_ will run from May 3 until August 5, 2018 (in parallel to Art Basel)

Over five decades, you have been exploring the relationship between humans (mainly women) with technology, identity, surveillance and the use of media to empower against censorship and political repression. As a witness of the different social and political movements since the 1960s, how has your artistic practice evolved alongside the socio-political changes over all these years?

My experience in the ’60s shaped my political interests and efforts. Being a natural part of the free speech movement in Berkeley and watching the formation of the Black Panthers and Woman’s Movement, I began to understand the generation of content in work and how art could affect social change.

Your upcoming exhibition, Anti-bodies, will be a solo exhibition bringing together your latest work on biotechnological developments. Lynn, could you tell us a bit about the intellectual process behind it? And Thomas, could you tell us more details about Novartis’ role in the Antibody room project and how it got involved?

Lynn: It came purely with my investigations that began in 2006, understanding that programming the genome was one of the most important acts of this era. I set out to investigate the effects of this by contacting scientists, sometimes Nobel winners (in this case, Elizabeth Blackburn, who agreed because she had seen my film, Conceiving Ada) and visiting labs. The information I garnered with the more than 18 labs around the world shaped The Infinity Engine. It was through dialogue and understanding the possibilities now available that the lab was shaped.

Thomas: Lynn Hershman approached Novartis to gain more insight into antibody discovery processes and applications. To explain our research activities and to personalise what Novartis is doing in research, the idea was created to design a novel antibody. Antibodies are made up of amino acids. There are 20 naturally occurring amino acids, typically abbreviated by a letter, e.g. leucine = L. The novel antibody will reflect Lynn’s name in its amino acid sequence, making up the region usually important for recognising antigens.

The Lynn Hershman region of the antibody will mediate its unique character. Our part was designing, producing and profiling the antibody and generating data and reports of the process. We will further provide some scientific equipment and the actual LYNN HERSHMAN antibody for the exhibition. It would be great if the LYNN HERSHMAN antibody project may trigger some thoughts and excitement around the field of therapeutic antibodies in one or the other visitor.

In Antibodies, you will be presenting for the first time The Antibody Room, featuring the development of an artificially engineered antibody that bears the name of Lynn Hershman in its molecular structure and was developed In collaboration with Novartis. What were the biggest challenges you both faced in developing the project?

Lynn: I did not see any challenges. I worked with a great scientist, Dr Thomas Huber, and the main challenge was seeing what this anti-body’s function would be on April 24. For the DNA conversation, I was lucky that the scientist’s brother was a sculptor, so he was sympathetic.

Thomas: Sharing research activities with non-scientists is often challenged by the complexity of the topic. Creating a personal connection and allowing a different perspective may facilitate it. For example, how well can the LYNN HERSHMAN antibody be produced? May it have unique features? Could it treat diseases? Questions no one can answer before running the experiment. Novartis typically looks at an extremely high number of different antibody sequences to identify the single one with the desired properties. Starting with only a single line bears an increased risk of the antibody misbehaving. So it was a great relief seeing the first production data indicating that the LYNN HERSHMAN antibody was perfect.

Thomas, could you tell us more details on the characterisation of the antibody? Have you used fluorescence technology (which can also have an artistic aspect) to identify any target antigen or potential therapeutic pathway?

Therapeutic antibodies typically aim at extracellular (secreted or cell membrane-bound targets). For the Lynn Hershman antibody, we have indeed chosen a fluorescence-based assay based on a recombinant protein CHIP array with around 7000 different secreted proteins spotted. However, Swiss TV wished we would evaluate the CHIP experiment only when Lynn visits on April 24. Thus, we don’t know the results yet.

A therapeutic antibody optimally recognises the single protein for which it was selected and is not binding to any other. For the Lynn Hershman antibody, we defined the sequence of the antibody and are probing for a potential binding specificity. Due to the long critical loop, I expect it may bind weakly to various proteins. If we saw a more defined specificity or no binding to any proteins, that would be extraordinary. But we have to see… So it still is an exciting experiment to run.

Lynn, what were you most surprised about by closely working with scientists? What were you most fascinated by their research on antibody development techniques? And Thomas, has collaborated with artists impacted how you view some aspects of your research?

Lynn: Science is very creative, not different from making art. The difference, in this case, is you are working from the inside out of the human structure directly and making shifts that will enable recovery hopefully.

Thomas: Scientists are trained to anticipate possible outcomes before running an experiment. This may also be reflected to some degree in the way they define as role of a project team member. Input might be provided according to expectations. Lynn has a very open mindset. This open frame allowed this anti-body project’s rather “unconventional” idea.

The Antibody Room culminates your body of work, exploring the concept of “anti-body” or alter ego. This line of work started more focused through your examination of virtual identity in cyberspace and has evolved with a new set of meanings since the development of biotechnology. An antibody seems in your hands the ultra representation of identity in the form of a reactive molecule (which actually can even be reactive against oneself). In which ways do you think the new biotechnological advances are changing or affecting human behaviour towards identity ethics?

Lynn: Absolutely. I think I was always making antibodies. Antibodies identify toxins in the environment and attempt to neutralise them. This is what art does. Biotechnology and ethics are no different than anything ethics. It depends on the individual.

Antibodies seem to have always been part of my art practice. An antibody identifies toxins in culture and then attempts to neutralise or erase them. Roberta Breitmore and later Roberta’s viralised representative multiples illuminated the rampant toxins of sexism in her 1970s era. By the mid-1980, antibody photographs appeared. In 1995 the text “Romancing the Antibody, Lust and Longing in Cyberspace” was published.

While the search for antibodies exists in all of my works, identifying the antibody moves inwards with this project and becomes an inverted biological gesture that has as its goal healing from the inside out, a cyborgian dream of infiltrating the body itself and thereby attempting to create a radical and curative recovery of individual culture

Why do you think bringing artistic projects in collaboration with scientific labs is interesting or relevant?

Thomas: Science and technology are progressing at an incredible speed. Key drivers are innovative ideasStepping out of the “routine” work and being exposed to new perspectives can provide the freedom required to find new solutions. Art can offer those perspectives. But on the other hand, the collaboration between science and art offers a unique opportunity for people outside the lab to discover science inspirationally. And finally, it also brings scientists outside the lab to an audience that might be “scared” by the complexity or have not had the opportunity to get involved in scientific topics.

Are you optimistic or pessimistic about the future?

Lynn: Optimistic.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

Lynn: Administration. Overwork. No time. The burden of people not understanding what I am doing.

You couldn’t live without…

Lynn: Time, meditation, immersion into the poetics of living.