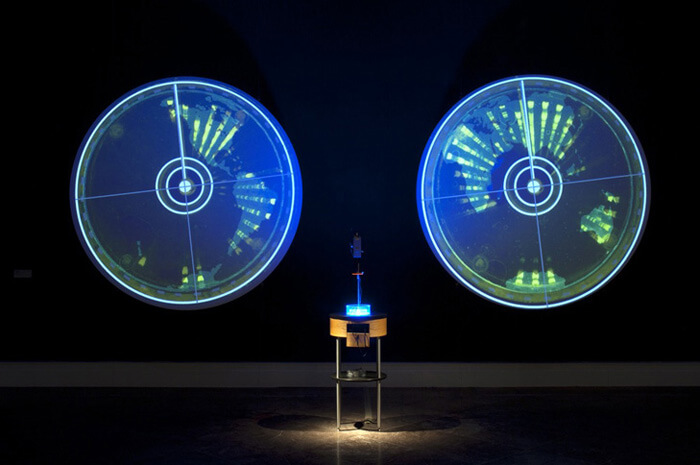

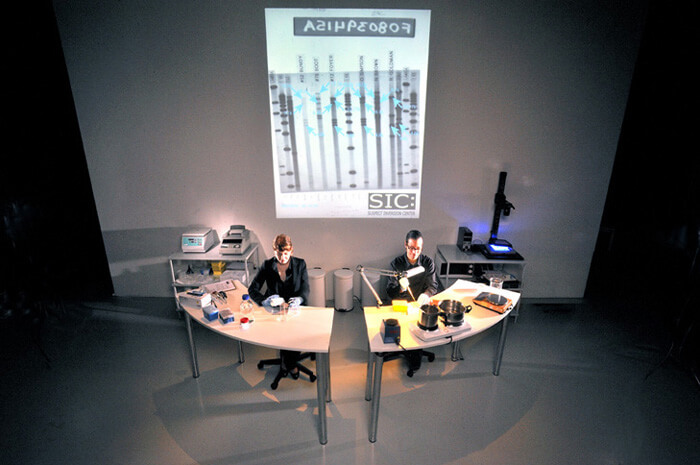

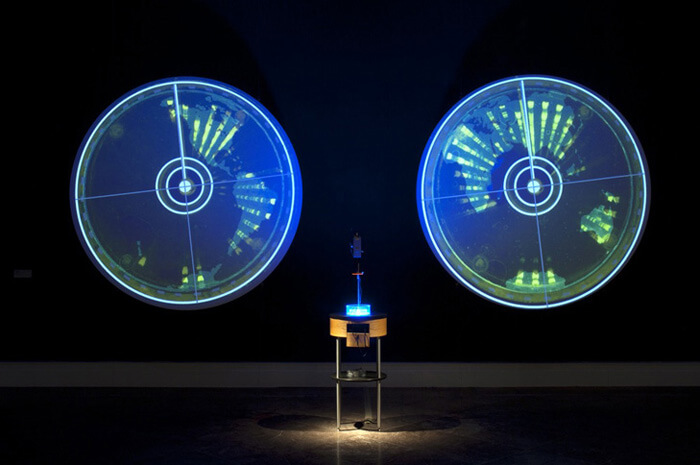

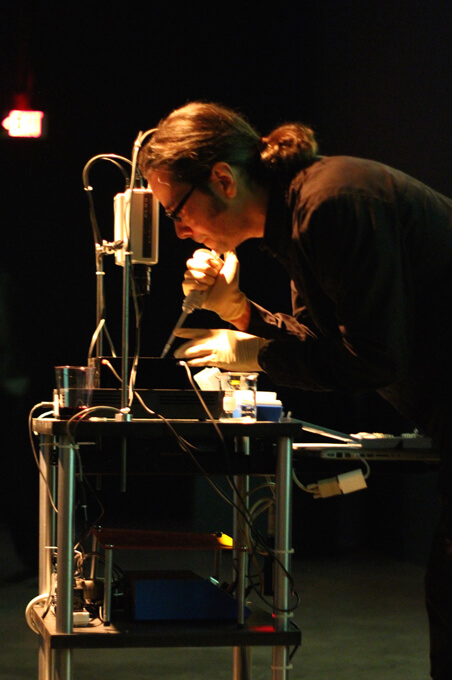

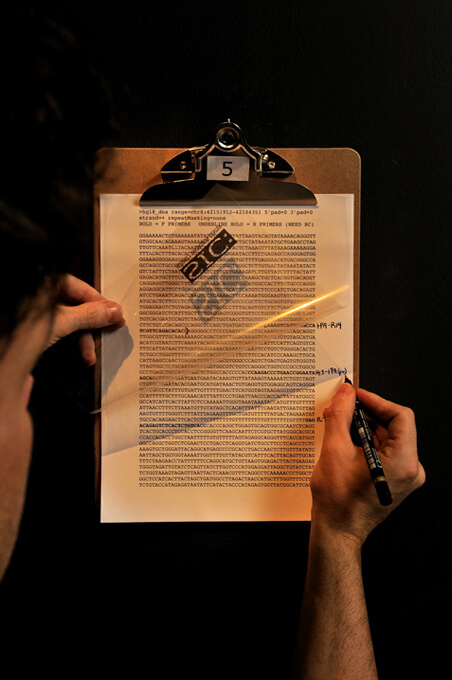

Suspect Inversion Center, Ernst Schering Foundation, Berlin. Paul Vanouse and Kerry Sheehan performing (2011). Photo credit: Axel Heise

There seems to be compelling evidence that we are entering what is called the “Anthropocene” era, a new geo-historical period in which humans are supposed to have become a major threat to life on Earth. The term has also profound philosophical and socio-cultural implications, as life typically becomes an object of reflection when it is seen to be under threat [1].

Paul Vanouse, a media artist and professor of Visual studies at the University of Buffalo, has been questioning techno-scientific practices since the early 90s: genomics, DNA and biopolitics are central issues in his works.

Vanouse’s interdisciplinary and DYI approach (perfectly exemplified in Deep Woods PCR), explores emerging media forms, in which the pieces are not concerned with the representation and/or presentation of an aesthetic object but rather with the tension created between the viewer and the viewed: the medium becomes the message [2].

His recent projects take advantage of molecular biology techniques, like DNA electrophoresis, to challenge the current genomic hype or even the genomic dictatorship.

The image of the DNA fingerprint (an individual specific DNA band pattern) as the ultimate truth is put under scrutiny with extremely aesthetically appealing pieces like Relative Velocity Inscription Device, Latent Figure Protocol, Ocular Revision or Suspect Inversion Centre.

The meta-implications of such an authoritative figure (like race, gender, culpability) are confronted by means of altering their representation and bringing them into abstract frameworks. In his new and ongoing project, Labor, the artist shifts from DNA to bacteria as his medium but he keeps addressing strongly socio-politics influenced topics, such as labour exploitation.

Biotechnology has brought upon us the technicalization of life and with that what is being called, an “epistemological turn”, is making artists consider the way in which knowledge and objects are presented. Paul Vanouse, with his smart and insightful take on techno-scientific issues, is definitely helping reshape the socio-cultural and philosophical frame for this new era.

You are an artist working in the intersection of art, genetics and techno-science, when and how did the fascination with them come about?

Growing up I watched Tom Baker, as Dr Who, perhaps that is why I majored in Art in college but also took classes in Biology, Chemistry and Math. I’d been working with interactive media since I graduated college in 1990, but many of the strangely perverse iconic biotech projects of the late nineties provoked me.

I couldn’t resist commenting and critically engaging. Endeavours like the “Visible Human project”, in which a death row inmate is cross-sectioned, photographed and immortalized as a digital “Adam”.

The “Vacanti mouse,” is a highly misleading image showing a lab mouse sprouting a human ear from its back. The existence of such things, as well as of course the Human Genome Project, left me little choice but to critically engage.

In the early 1920s, Cubism helped physicist Niels Bohr determine the quantum theory when he compared the behaviour of electrons with Cubist paintings. But, in your view what is the contribution of science to the arts?

For scientists, I suppose the motivating desire is to understand the natural world, while my motivating desire is to understand the way the sciences make sense of the natural world. You see it’s sort of a question of where one places oneself as an observer. So science helps to provoke me, to challenge me and to give me an object and relationship upon which to reflect and obsess.

Is art helping understand scientific issues or it is challenging what society understands about them?

Art is helping to open up this dialogue. I think the type of challenges that art is providing help to make sense of the world, as the arts have always historically done.

What are your aims as a bio-artist working between science and art?

To blur the lines and form monstrous interdisciplinary hybrids. To create new forms of creative scholarship and apply the critical and observational tools of art and visual studies to new things. Lastly, to work in a way that is consistent with good art and to continue to challenge myself.

If you could visit a scientist’s mind, who would it be and why?

Eighteenth-Century naturalist, cosmologist and mathematician, Compte de Buffon I suppose. Such a broad thinker, he possessed some of the deep flaws of Eurocentric views of race and mankind in the colonial era.

But also transcended his era in his understanding of the natural world not just as a static grid-work of classification, but as dynamic and transforming, plastic and creative. I’d like to understand the reasoning as well as the societal pressures that created both these facets.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

iPhones.

You couldn’t live without…

Borges.