Interview by Živa Brglez

Anthropocentrism is one of the main fields in which Slovenian scientist-turned-artist Špela Petrič not only addresses but also intervenes in. With her artistic practice, a blend of natural sciences, new media and performance, she tries to put forward a more egalitarian, self-reflective and critical world’s view. In her work, she is combining and challenging and contributing knowledge from and to several different disciplines – from biology, biochemistry and biotechnology to anthropology, psychology and philosophy.

Petrič is not merely representing or illustrating the scientific part but carefully transforming the formal scientific content into visual art, all while keeping the basic scientific foundations/facts, which she diligently presents through their inner processual quality. In her artistic practice, she tries to pinpoint the reconstruction and reappropriation of scientific knowledge. Petrič is deriving her practice through two main vantage points, the first being researching “living systems in connection to inanimate systems manifesting life-like properties” and the second being “teRabiology”, which is an “ontological view of the evolution and terraformative process on Earth”. Her practice often operates within the realm of ethics – for example, why are interventions into human cells or tissues seen in a wholly different and problematic way vs interventions into plant organisms – and thrives to put forward a new, different, post-anthropocentric bioethics.

In the last years, Petrič has been working on a series called Confronting Vegetal Otherness, which is an attempt at plant-human inter-cognition. The first strive was made back in 2015 with Skotopoiesis (meaning shaped by darkness), a durational performance with the aspiration of making a plant an equivalent subject of an event. For nineteen hours, she obstructed the light and hence cast a shadow onto the cress. Effectively, that stimulated the production of auxin, a plant’s hormone, and resulted in the whitening and elongation of the plants placed inside her shadow.

Consequently, the performance was not only a face-to-face between the human and plant, an event of artists’ immersion into plants, but also a responsive exchange between their respective appearances – while the cress morphologically changed, the artist also did, her body shrink (as one human’s backbone does, standing in place for a long time).

In Strange Encounters: Metaphysics, Algae and Carcinoma, the third piece of the series, she attempted human-plant inter-cognition on the cellular level, more precisely on a level of intercellular communication. Algae cells encountered carcinoma cells, and they “met” each other. Equipped with the insights gained from the series, she is opening a new chapter of her artistic endeavours.

Just recently, in Kapelica Gallery, she opened a new exhibition titled Nociceptor: lip reading. It is a presentation of a project, which is an attempt of repeating a made-up, not yet started scientific experiment in which a “linguist and polyglot Mi Yu” “attempted and achieved “a meaningful exchange between a Ficus benjamina tree and a human, which could, in a broader sense, be described as a conversation”. It conveys an interesting conceptual shift: from thinking of communication tools, such as language, as inherently and solely human to think how to create or establish one that would potentially enable us to have a chat with plants.

Your artistic practices combine natural science, living systems, new media and performance with a re-appropriation of the scientific methodology. For those that are not familiar with your work, could you tell us a bit about your background and when and how did the fascination with biological systems come about?

I’m trained as a scientist. Perhaps that is not at the root of my fascination, but likely the reason I referred to living beings as “biological systems”. Biology is the softest of hard sciences and cultivates a certain intuitive understanding of how life functions; along this, one also develops a strong sense of how misleading it is to think of organisms or ecosystems in terms of control and manipulation.

Having worked so well when applied to technology, these strategies and mindsets are disappointingly falling short of, e.g. improving social justice, increasing care for the environment or balancing wealth distribution (human societies are, after all, also living systems).

So we have to ask ourselves – what did we miss? And this is the first instance of where I find the hybrid field of art has the opportunity to look closely and deconstruct “the master’s tools” to reveal the hidden principles of onto-epistemologies and better understand their effects, which is what I’ve been pursuing throughout my work.

But while a critical consideration of technoscience and its paradigms might be a practical, material approach to topics that have already been extensively addressed in discourse, I’m also interested in art’s potential for new constructions – that are different ways of relating to these complex processes, increasingly allowing ourselves to think through bodies as opposed to prioritising the mind and its logos, which, we must admit, can also be manipulated and irrational.

Life and its strange principles connect phenomena we constitute and are embedded in; it’s a privilege and responsibility to experiment and learn with art creation on such relevant and urgent topics, especially through collaborations with wise and knowledgeable people from a range of fields.

Confronting Vegetal Otherness series looks at plant alterity to reassess subjectivization, ethics, and our attitude towards individual multiplicity (in your words). What are your artistic and intellectual aims behind this series?

The series started with the realisation that my long-standing ignorance of plants could be put to use as a study on alterity as such, on the limits of empathy and of possible ways the overcome the insensitivity associated with what we don’t or don’t want to understand. From the outset, the art and research project was structured into three chapters, with the hope that the insights from each step will inform the next.

The ontological divide between plants and people would be addressed with novel and strange relationships enacted on three levels of scale and organisation – the cellular, the individual and the communal. The smallest level of the encounter was observed as a micro performance called Strange Encounters, during which I instigated a meeting between human carcinoma cells and the algae Nanochloropsis. In Skotopoiesis, I was casting a shadow onto germinating cress for 20 hours in an attempt to communicate with it through (the absence of) light.

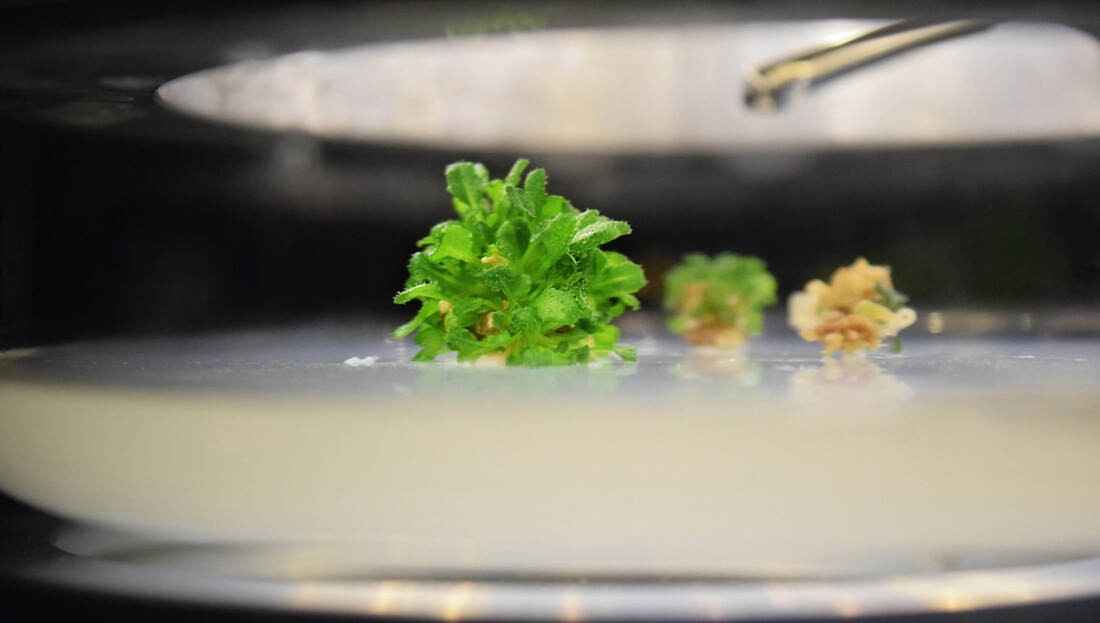

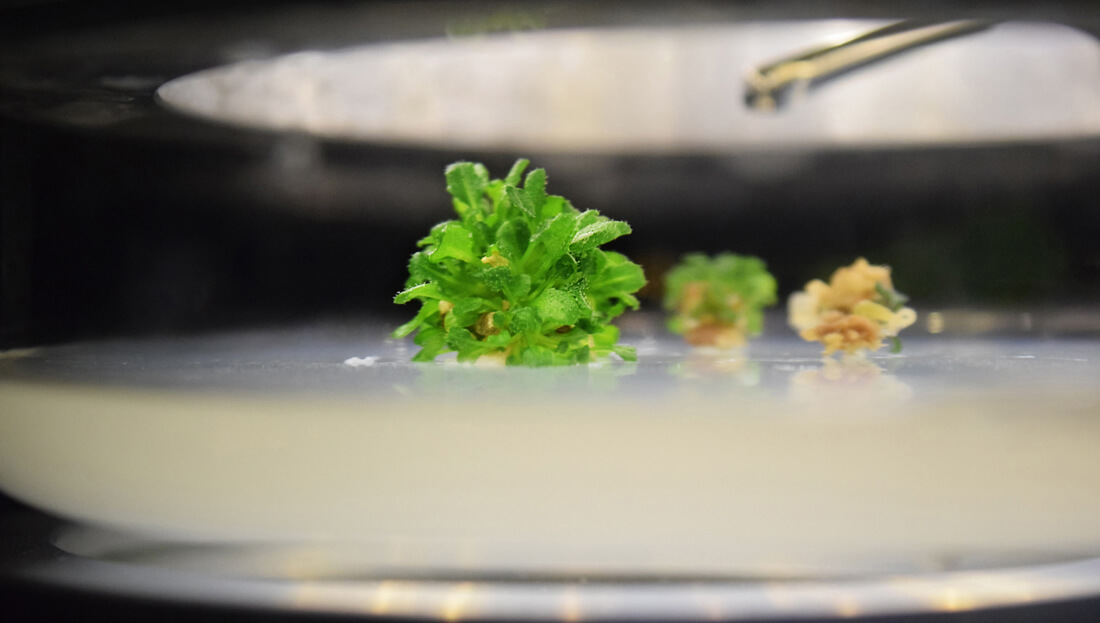

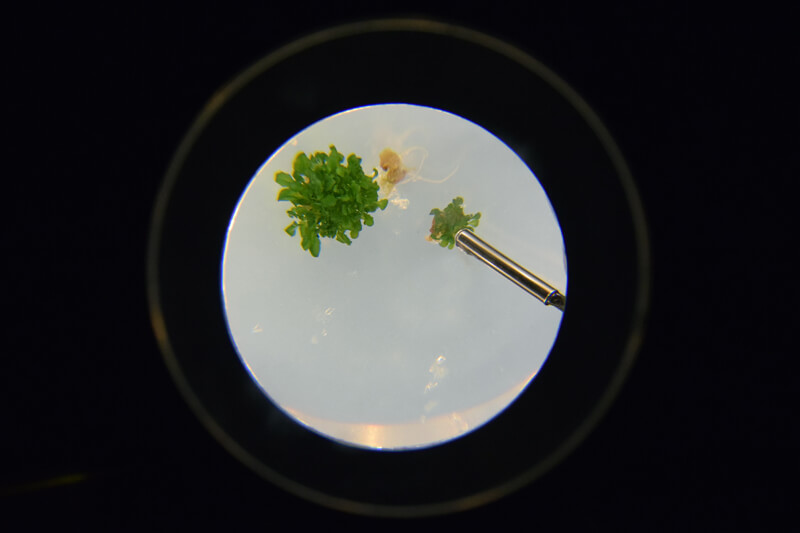

For Phytoteratology, I created plant-human monsters in artificial wombs with my hormones mediating contact between the plant (thale cress) and myself. I enacted the human individual, desperately trying to present herself to the plant in its perceptual milieu. I also failed to achieve a certain perceptual, visceral satisfaction, feeling that somehow the use of scientific apparatuses and methods was getting in the way of an authentic exchange. This was also the point of frustration that ultimately leads to transformation, that is to a rethinking of the artistic methodology chosen to construct new relationships with plants.

The result was the final chapter called Deep Phytocracy: Feral Songs, within which I addressed the question of plant agency in a deeper time and at the scale of communities. Instead of drawing from science, which in the previous projects seemed to both legitimise my endeavours as well as alienate some of the viewers, I wanted to share some of what I had learned from plants during the Vegetal Otherness opus in a non-linguistic manner (since that was also the way that the plants transmitted this ‘knowledge’ to me in the first place).

When curator Vytautas Michelkevicius invited me for a residency on the Curonian Spit (Nida Art Colony, Lithuania), which has an intriguing natural-cultural history of its own, I realised that it was the perfect opportunity to work outside the gallery space and explore phytocracy as a participatory artistic form.

What was the biggest challenge you’ve faced in the development of a particular project?

Well, precisely, Feral Phytocracy posed one of the bigger challenges I’ve faced so far, and for several reasons. First off, it was my first solo foray into a participatory format unrelated to scientific narratives but with an attempt to convey the inextricable link between the tools we use to relate to the world and societal values. This ambitious aim was further complicated by my wish that the artwork is inviting to people of different ages and walks of life.

Moreover, I was trying to share an unutterable experience that formed through my many encounters with plants. The more I researched the topics, the more the artwork escaped me – until I started working with participants. Some events were held as workshops, others work-in-process performances, but overall more than two hundred people helped test the narrative and tool prototypes. And the best reward for me is that four years ago, I never would have imagined this to be the concluding piece.

What directions do you see taking your work into?

I think it’s time to take the vegetal insights and, through them, closely look at our societies. I’m completely mesmerised by a term I heard from feminist philosopher and critical theorist Catriona Mortimer-Sandilands: the vegetariat. What does it mean to politically and socially exist as the vegetariat? She’s not the only one that sees potential in this framing: Jeffrey Nealon wrote about the image of the vegetable far better characterizing our biopolitical present than the human-animal image of life, which remains tethered to the individual.

Somehow it is both frighteningly reductive and resiliently proliferative. To me, it encapsulates what we experience as consumers, as citizens, and as data, and I’m on a mission to make an incubator for the vegetariat.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

Exhaustion. Not just artists, everyone seems to be working increasingly long hours – and in many instances, for ever-smaller payment.

You couldn’t live without…

Caring.