Interview by Meritxell Rosell

There’s a particular type of artist (or musician) who, no matter how many years active, still possess an immense drive for discovery and experimentation. This is the case of Coldcut, the English electronic duo pioneers of sampling, mash-up and cut n’paste since the late 80s. Described as two unruly children who won’t sit still, the duo celebrated their 30th Anniversary last year. A lifelong adventure that started in 1986 when the computer programmer Matt Black and ex-art teacher Jonathan More met. During their career, Coldcut’s music has always been accompanied by innovative video and multimedia projects, becoming one of their signatures.

Matt and Jon are also the founders of Ninja Tune, the renowned independent record label, with a focus on encouraging interactive technologies and finding innovative uses of software. Ninja Tune is nowadays a worldwide reference and still putting out the most forward-thinking music and artists such as Bonobo, Cinematic Orchestra, Roots Manuva, Thundercat, The Bug, Actress and more. The label’s first releases were produced by Coldcut in the early 90s and composed of instrumental hip-hop cuts that led the duo to help pioneer the trip-hop genre.

Coldcut has also been a pioneer in creating and using video games, collaged videos and apps for their shows and performances (i.e., Playtime, which developed the auto-cut-up algorithm used at the first edition of Sónar Festival in Barcelona in 1994). We could describe in length their many collaborations and projects expanding all sorts of artistic disciplines, how much of a cornerstone their productions were in developing UK dance culture in the 90s and the important contributions they have made. But Coldcut has always looked a step ahead, and similarly, we’ll focus on their most recent endeavours.

To mark their 30th anniversary, Coldcut put out a new album, a new Audiovisual show (which incorporated AI and neural networks generated art) and a slew of apps and tech products. The album, Outside the Echo Chamber, is the duo’s first in ten years, and it was produced by Adrian Sherwood. Described as a wild electronica soundclash, it includes contributions from master veterans Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry and Roots Manuva, among others.

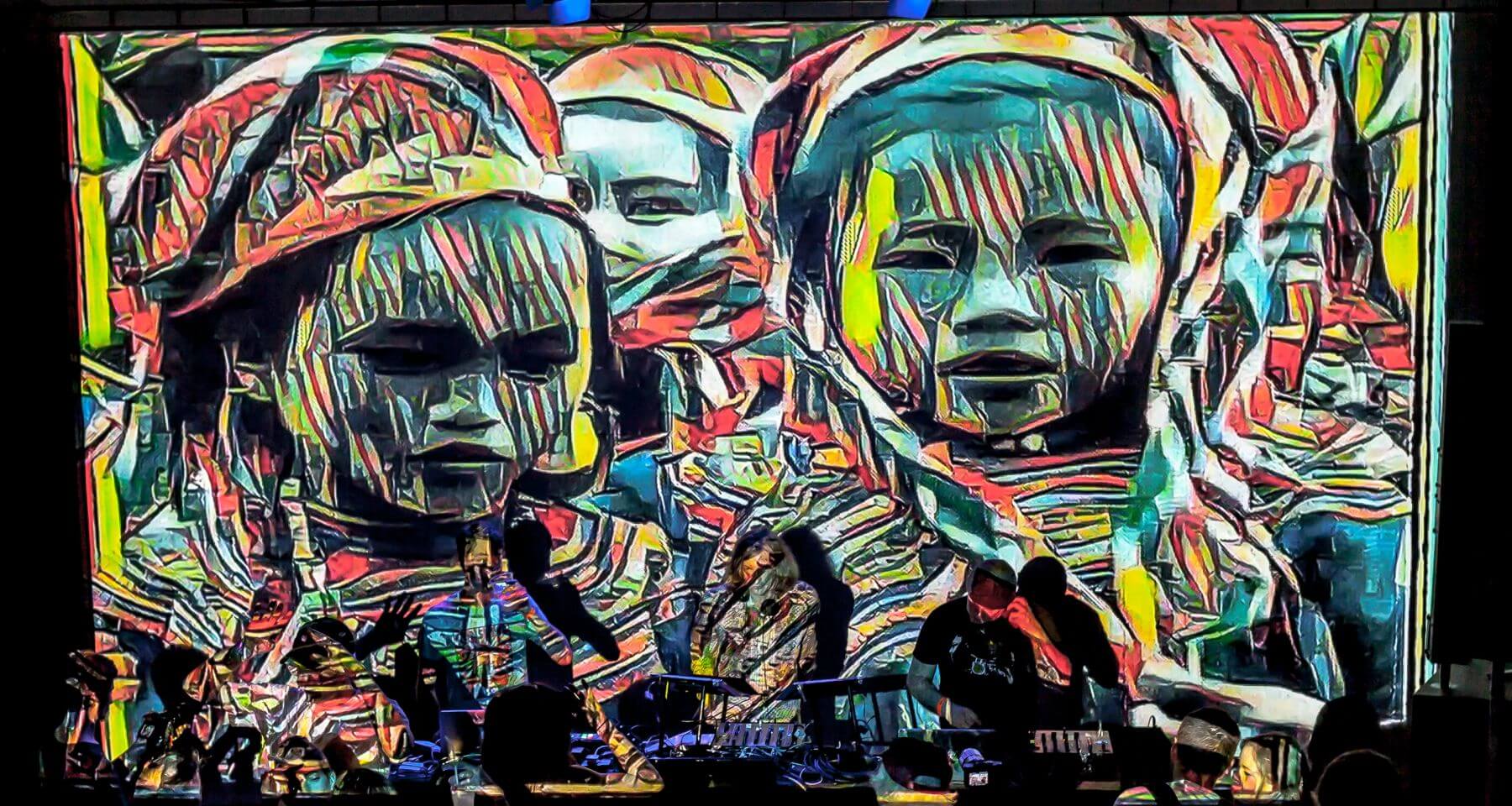

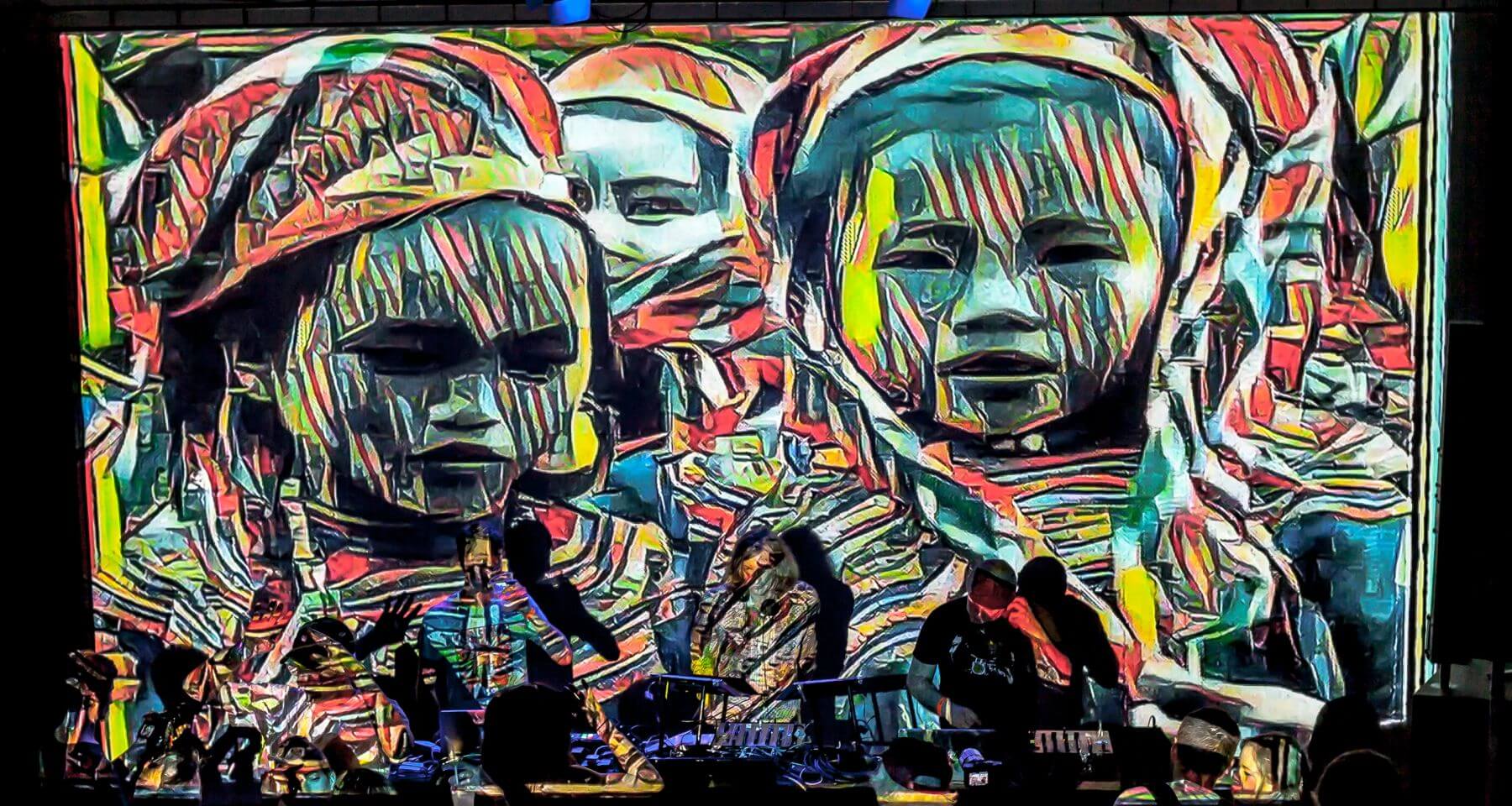

The AV show included Coldcut’s classic visuals reinterpreted using ‘Style Transfer‘, a new technique that uses AI technology to interpose the visual tone of one image over another. Style transfer arose from a collaboration with the Deepart team from the University of Tubingen, who invented the technique. The art it produces is deeply haunting. The show also uses Coldcut’s latest inventions, including ‘Pixi, an iOS-based artwork synthesis app that enables users to create accompanying visuals while they play’ and their ‘Jamm’ app to remix tunes live.

Aside from the new album and their anniversary shows, Coldcut has kept even busier creating MidiVolve, a composition software for Ableton that offers producers and DJs a set of tools to develop new riffs and rhythms. MidiVolve marks a new way of creating music by turning MIDI patterns into a naturally evolving musical continuum with the instrument and effects racks derived from Coldcut’s sonic laboratory. Their approach is inspired by Steve Reich’s systems music classic ‘Music for 18 Musicians’. Coldcut has been at the forefront of mash-up culture for decades, and these new projects are just the latest turn in a career spent bringing remixing – of art, technology, and ideas – into the mainstream.

Inheriting from the 1920s dadaists and the 60s beatniks, who discovered new creative horizons by cutting and pasting texts, pictures and even ideas, Coldcut dedicated a 30-year expanding career to bring this artistic practice to their own territories. Matt Black said that he hopes they’ve made a fruitful contribution to the growth of electronic music and culture over the last thirty years and that people will see that reflected in these new shows.

Incorporating technology or new technological advancements- from software and programming to musical and visual art itself- into your shows/productions have been central to your 30-year expanding career. How and when this interest in different technologies comes about?

I’ve been interested in technology since I was a child, since the 60s. I was really into science fiction and toys like robots that flashed and made sounds. I used the sound and light for shows for my family, using the sounds messing around with old radios and bows, buzzers and lights and switches and motors. From that, it was a natural progression mixing science fiction and science to more advanced technologies like building analogue synths in the 70s and getting into programming in the mid-70s.

So the technology threads of Coldcut is something I’m very passionate about. I must also mention the influence of The Selfish Gene by Richard Dawkins. It was a book that blew my mind when I was about 14-15 when it came out. The ideas about the similarities between computer code and DNA and the views about memes, modelling behaviours, and software fascinated me. So I realised early on that digital tools such as computers could be used to make digital art: music, pictures, video, software…

For Coldcut’s 30th anniversary concerts, you prepared a special audiovisual show, where classic Coldcut visuals have been reworked using a new technique, ‘Style Transfer’, which uses AI technology to interpose the visual tone of one image over another. Could you tell us more in detail about how the algorithm (AI) works? What was the concept or intellectual process behind the project?

A team at the University of Tubingen were the people who first invented the algorithms, which then spread like wildfire. That became possible because of the development of new types of artificial intelligence algorithms, particularly neural networks and applications and structures related to those so that mushroomed and made considerable advances in the last five or six years.

Regarding neural networks, the so-called machine learning and Google were big players as well. In style transfer, it’s all about image classifiers. So you teach in to work on many images, so the algorithm learns to classify images. That means it tries to understand what features and the different components of pictures are; on some level, we can say that the algorithm knows what’s in the picture.

To me, I’m pretty hazy on the technical details, but the image classifier neural network is used to abstract information from a styled picture, let’s say, a classic example, Vincent van Gogh. He has a very distinctive style. Style transfer would somehow abstract the colour palette, the use of colour, the textures, the brush strokes and somehow even the representation of features and then apply that to a second photo, the content photo.

So it applies the style and transfers that to the content (or target photo). And so then, the neural network tries to reinterpret that content image using the information from the styled image. In a way, it’s like some intercourse, sexual intercourse, between the two threads, the two pictures which go into generating a new picture.

I have been interested in AI for a long time, and I’ve been following the development of neural networks for some time. Since I’m not an expert, I’m interested as an artist, and also I’m interested in using computers and the latest technology, which I’ve always been into. There’s a friend of mine, William Rood, who is a programmer, and I’ve worked with him on lots of projects. He has been interested in AI and neural networks for a long time as well.

I got introduced to some people from the University of Chipping I made a deal with them where I could render the frames on their servers using the most advanced transfer algorithm. So the new video is just a series of frames put together, a series of different sequential images. By sending sequential images to a stock transfer program and applying the same style to each of them, you can still style transfer a whole video.

And that’s what I did with Timber [one of Coldcut’s hits]. William Rood wrote me a Python script to take my videos and turn them into frames to upload to the University of Chipping. The server would render them using the stock transfer, then get the results downloaded to our computer and then compress them into a video. With the result of the stock transfer efficiently being applied to our source video. I took Timber and run it through various stock transfers. I edited them together to provide one version of Timber, which has got these different sorts of skips between these different styles. So in a way, this is a form of sampling.

What were the most significant challenges you faced when using Style Transfer?

Technically it was quite tricky to get, but when you got it working, it’s fantastic. Subsequently, Billy and I bought some high-spec chips which can be used to do the stock transfer, so he’s playing with those. It’s best to render them under Linux. We found it’s much more efficient. In Windows machines, a lot of the power is wasted due to its bloated nature, but with Linux, you get more down to the metal, so you get better performance.

You have also recently launched MidiVolve, a collaboration with Ableton that marks a new way of creating music by turning simple MIDI patterns into a naturally evolving musical continuum with the instrument and effects racks derived from “your” sonic laboratory. Your approach is said to be inspired by Steve Reich’s systems music classic ‘Music for 18 Musicians’. Could you expand on the inspiration and the novel aspects of the invention?

So once upon a time, we were doing a radio show for Network 21, a pirate station in London. I was like, OK, what are we going to start with? John said: I know what to play. It was clear to me that it would be an arty thing.

It needed to be something a bit more abstract and arty, and John stocked music from great musicians. I had never heard anything like that [Music for 18 musicians]. And then John mixed into this Ligairi double track, With disco devil or something like that. And I thought it was such a brilliant way to show how a DJ could jump from one track to another. You could make an interesting connection and a statement showing there’s a relationship between them.

The repetition of views, of space… That’s how I came to love the music of the most exceptional musicians. I’m not sure how we got to remix it. I think it was the piece’s 17th birthday celebrations. We thought it was a real challenge. John and I pulled [Paul] Brooke, who used to program the music for quite a lot of Coldcut tracks, and we worked out the score for Music for 18 Musicians and transcribed it into digital MIDI notation.

I don’t think our remix is a masterpiece, but it’s not bad. How would you improve on one’s favourite piece of music? After that, we got to work with Steve Reich as well. We were able to do another show in NYC and one in London.

The piece is his masterpiece, and it’s a systems music where you can describe it a long way. But systems music, and perhaps minimalism, it’s actually quite maximalist, though, because, for example, with 18 musicians, it’s not just like one piano or even four organs. But it does combine a lot of Reich’s ideas about phase shifting and systems, and in my opinion, about minimalism as well. The piece is very simple, or it seems very simple. Nevertheless, the parts slowly evolve, coalesce, merge and mutate, and there’s a great sort of ebb and flow and structure to it.

John and I both loved those guys and their work. We wanted to do something like that. With Music for 18 Musicians, we wanted to make music like that, but to do it requires you to be a composer and to have a whole orchestra. Well, I’m not a composer, and I haven’t got an entire orchestra to hand.

But I’ve got my computer, so it could be fun to break down some of the ideas of Music for 18 Musicians and implement them in an algorithmic instrument that would aid someone such as myself to emulate these great composers.

The Coldcutter [another of Coldcut’s creations] takes a piece of audio, chops it into equal bits and then starts shuffling that buffer. MidiVolve is similar, a riff generator and sequencer that turns even the simplest of MIDI patterns into an evolving musical continuum. Steinberg’s interactive phrase synthesiser incubates a similar sort of idea, but it’s more complicated. I think I used it once, and it was amazing but too complicated, and I wanted to embody some of these ideas, some of these abilities and something that is easy to use

Augmented and virtual reality are experiencing exponential growth in popularity in visual arts. How do you predict they will impact live music shows? Are these technologies something you would like to explore for your performances?

I love it all, but I find it difficult to imagine a ton of people wearing headsets. Some people predicted in 10 years time, there would be no screens, and we’ll use contact lenses. It will make these technologies a lot easier to wear without being so self-conscious and without insulating yourself.

You don’t want that wall [headsets] so that you can combine the virtuality with the real world is what I would say would be best. For live music shows, maybe we should wait for, as in William Gibson books, to jack the experience directly into your head, a socket it behind your ear. But of course, you will need to leave your room. But if you make me say contact lenses screens. I think that one can create an exciting cutting-edge platform for integrating virtual experiences into shows.

What is your biggest enemy of creativity?

I don’t have enemies. Everything’s useful for my creativity.

You couldn’t live without…

Water. I could have said my wife, but I suppose I could live without her, and it would be soppy to say I couldn’t. But I feel I probably couldn’t. And to my wife, who is the most wonderful woman, I’d like to say I love her, and I hope I’ll never have to live without her. And she’s the biggest and best influence in my life.