Interview by Teresa Fazan

Dance is experiential. So many complex psychological processes occur when you move your body, and the moving body is so extremely dynamic; I wonder how an electroencephalogram (EEG can record all this complexity. This is the question Colleen Thomas-Young asked herself during her lecture at Columbia University in 2015. Three years later, she is in the middle of a study dedicated to understanding the processes of creativity and learning in different dance and movement practices. Together with her colleague, Dr Andrew Goldman, she decided to answer the question herself: one of the methods employed in the study is EEG.

Colleen Thomas-Young is an experienced dancer, choreographer, contact improviser and an Associate Professor of Professional Practice in Dance at Barnard College, Columbia. During her years of practice, Colleen developed a keen interest in the psychology of dance. She started wondering—how do we manage to repeat the movement performed by another body in front of us? How do we achieve to transfer the sequence onto our own body and, after just a few repetitions—remember it? Observing, reenacting and memorising the basic doings of dancers, the bare minimum they go over and over again every day. However easy to implement, the action of movement learning appears to be extremely difficult to understand.

This question stumbles both practitioners and researchers. Observing patterns of behaviour while learning and creating choreography has become the basis of many studies. Researching the processes employed during dancing may bring about knowledge about human cognition as such. Neurologists and cognitive scientists have been working on this topic for years, and different research methods have been employed to solve the riddle of movement learning.

However, when it comes to neurological research on dance, many problems emerge: electrodes peel off the sweated body, and wires make the movement impossible or at least restricted. The dancing body does not meet laboratory requirements on so many levels it is hard even to imagine a sufficient study. However, some possibilities are at hand: wireless electrodes are being developed, and the movement of the examined dancer can be narrowed down significantly. Despite restrictions, there is a possibility of creating a sufficient study. The work of Thomas-Young and Goldman proves it is worth a try.

Somehow along the way of your professional career as a dancer and choreographer, you developed an interest in the neurological aspects of movement learning and creating. Could you tell us what you are currently working on?

Currently, I am working on a project dedicated to exploring what happens in the brains of different dance professionals and non-dancers while learning choreography and improvising. I am collaborating with Dr. Andrew Goldman from Columbia University, who is not only a music theorist specialising in music cognition but also a trained classical pianist.

For the most part, he explores music improvisation and broader—creativity as such. We have already worked together: we were conducting a course about improvisation in music and dance. Since we both try to merge working as practitioners and researchers in our professional lives, the course also consisted of both theory and practice.

What is the intellectual process behind this study?

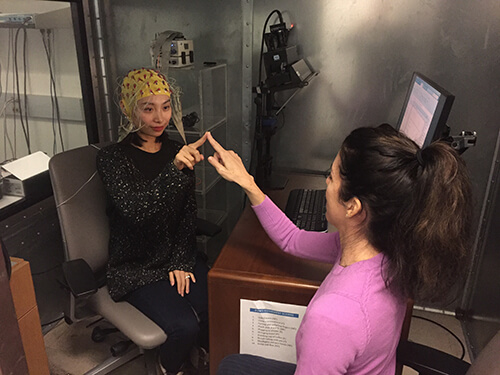

In this study, we are recording brain activity using electroencephalography (EEG) in order to research the movement learning process among different dance specialists and non-dancers. We are looking at three groups.

The first one consists of the contact improvisers, so dancers who do not learn choreography on a daily basis. Second, are the technical dancers who do not improvise frequently but are trained in learning choreography fast.

And the third one is the non-movers, so people who do not move at all in terms of dancing in their everyday life. We are examining differences in the neural correlates of movement between these groups and differences in the brain activity associated with performing choreography versus improvising.

Is your research, then, focused on choreography learning?

Not only. We also want to research the notion of creativity. We are looking at the brains’ activities when the subjects do the improvisation versus when they do the choreography. What interests us are the differences between processing those two activities, so we are comparing the collected data within the three groups. But it is not enough to only observe the EEG results. I believe it is very important to observe the action itself.

Could you expand on this? What are the challenges you face in the development of the project?

For me, as a practitioner, there are interesting aspects of this process which are not displayed by the data. During the study, the subjects observe the action, which I repeat over and over again. Their task is to do the action and also repeat it over and over again exactly how I did it. Something interesting that can be observed but is not really spotted by the EEG is what dancers practising different techniques value during learning and creating processes.

Obviously, ballet dancers, improvisers and non-dancers value different things and hence memorise and learn differently. This study seems important because there have not been a lot of studies like that on dance—due to the technical difficulties: the wires, sweat, movement, and touch do not come together well.

When we conceptualise brain research’s subjects, we usually think about higher intellectual processes. Dance may not seem as such. However, the level of concentration and awareness you must maintain while improvising or focus and skills required during memorising the choreography actually makes them highly intellectual activities.

Of course! Learning and creating dance are highly intellectual activities in terms of embodied perception and cognition, just like meditating. Actually, this is the reason that got me wanting to do this particular study. Recently I have read some results of the studies on mediation. I think that something that is happening when you meditate also happens when you practice improvisation. The effort of being present at the moment, which, as we know from our everyday life, is extremely difficult. It would be very compelling and useful to understand what happens in our brains in such a state!

What’s your chief enemy of creativity?

Our internal critic. That voice that makes up stories – not true stories about what something is, should be, isn’t and needs to be etc.

You couldn’t live without…

Connection. Connection to people and the earth.