Words by Sebastian Kamau

Adam Peacock wears many hats. At times an architect; at others, a furniture and car designer, and yet still an editor and marketing guru. His circuitous path through these varied fields has given him both the vantage of the ‘bigger picture’ and the artistry of a craftsman when it comes to understanding the role of design as a way of interacting and responding to a cultural environment.

His most well-known work and the namesake of his current studio – The Validation Junky (2014) – took form as his MA graduation project from the Design Interactions program at The Royal College of Art. The program, at the time led by Anthony Dunne, was heavily influenced by the discipline of ‘Speculative Design’ and emphasized the creative reimagining of technology’s place in shaping the future.

In this spirit, The Validation Junky was an architectural methodology for understanding how human’s evolutionary psychology maps onto modern consumer culture surrounding identity, appearance, and social status. Originally a bound, hardback, limited edition book of architectural draft pages, it has now become the foundational discourse for Adam Peacock’s approach to design.

The designer’s approach places designers as necessary thought leaders for tackling the pressing issues of the day rather than the “empty rhetoric” of designing products for the sake of the products themselves. As he sees it, greenwashed trendy chairs, shirts, and the like will lose relevance as generations become more conscious of the negative consequences of technology on society. In time and due consideration, he believes projects and companies that bear this perspective in mind will be able to attain commercial success.

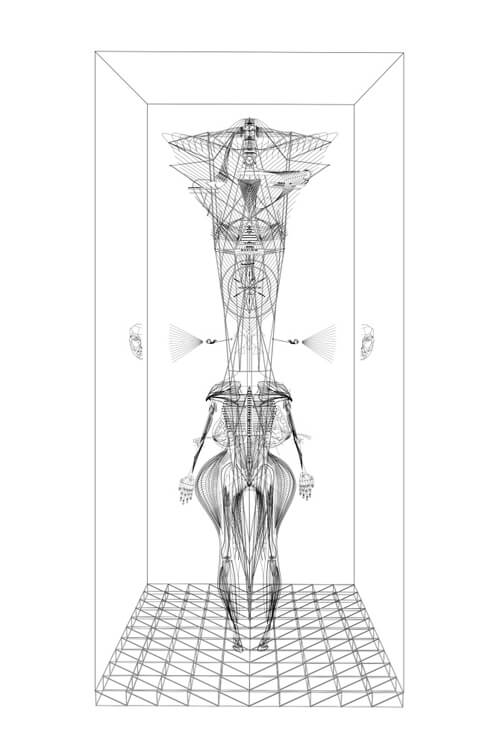

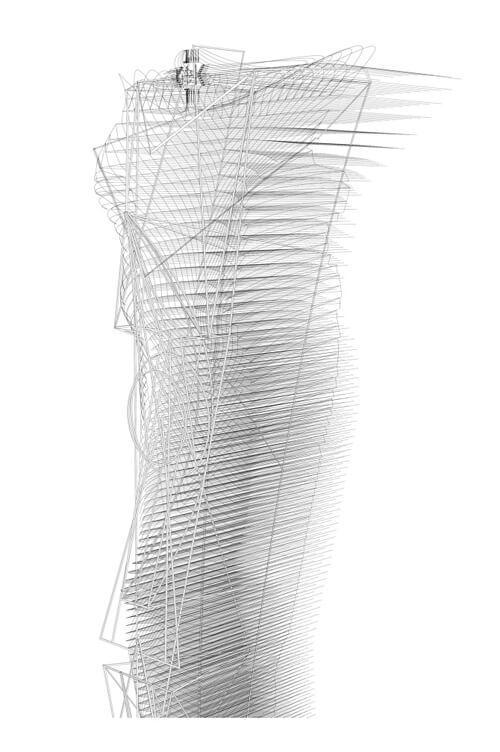

His most recent project, Genetics Gym SS18 (2017), tackles consumer psychology through the lens of five kinds of consumption behaviour: the unsustainable luxury ‘self-centred populist’, the punk ‘manifesto-visionaire’, the beautiful yet vapid ‘no-substance-visionaire’, the mainstream ‘basic-pleaser’, and the community-focused ‘common-consumer.’ The project loops each consumer into a series of behaviours that show the underlying pathology of each consumption behaviour. The project draws on the field of genetic engineering to create “a collection of re-designed aspirations in the form of altered bodies.” For Adam, this project serves as more of a raw expression of art and design capabilities than a scalable product with a direct commercial context.

While trained in Speculative Design, Adam Peacock is never far from design applications in commercial settings. His vision for contemporary design practice is a much-needed reminder – it’s possible to design products and services within a commercial realm that celebrates identity, not diminish it.

You have degrees in architecture, art and design. For those who are not familiar with your background and interests, could you tell us a little bit more about them?

The phrase I recently heard that best describes me is post-disciplinary designer. I think that the borders between design and art disciplines are being broken down by contemporary design, social and societal issues. They are challenged on one end by market needs and, on the other end, science. I believe that to be a relevant designer today means ignoring the rules of existing disciplines instead of responding with astute observation to form an intelligent strategy to frame how to approach a design opportunity.

When I chose what and where to study, I was informed by wanting to become the best designer I could possibly become within my means. I was curious about the skills and strategic processes involved in architecture and the Bartlett was known for its ambitious, progressive design output and seemed like a great skill base for a career in design. After graduating with a BSc. in Architecture at Bartlett, I worked for Amanda Levete Architects and, fortunately, took a day off to visit the MA Design Products Open Day at RCA.

Anthony Dunne, at that moment the course leader of MA Design Interactions, described a course that seemed like everything I wanted and needed, plus a bit of magic. He introduced the field of Speculative Design, an emerging method of design to accommodate the scope of what technology is capable of in the context of rapid digitalisation found within modern society. In short, design is to ask questions, not to solve problems. The MA was a ‘full-fat’ experience, quite painful from an existential perspective, turning me inside out and made me question everything I thought I was working towards.

My MA graduation project, ‘The Validation Junky,’ was essentially an architecture project. Still, instead of designing a building, I designed a mechanism using my architectural skills to observe and re-frame how the human brain perceives beauty, status, and attractiveness using theories found within psychology and human evolution.

The project addressed the idea that we are still attracted to the physical qualities associated with hunting, gathering, providing and protecting that our caveman ancestors 44,000 years ago gave us – now being out-evolved by rapid technological development through overstimulation from endless scrolls of edited imagery through new media; visually refined sugar for our brain. It framed a critique of how technology might be better conceived for today’s human motivations and desires.

Whilst at the RCA, I worked on a project for FIAT to lead the strategy for a small team of vehicle designers on designing a future FIAT 500, their iconic two-door city car. I used the investigative framework I had developed to create ‘The Validation Junky-lens’ to discuss how the car can be created for emerging technology and the future consumer.

After leaving marketing behind, I took up residency with the experimental tech-thinker lab ‘Visible Futures Lab’ at the School of Visual Arts (SVA) in NYC. I received a commission to produce a design exhibition, lectures, tutorials and workshops for SVA graduate students to explore the social and ethical ramifications that might occur if ‘a machine to automate beauty or appeal’ was developed, a direct follow-up of ‘The Validation Junky’ project from the RCA.

I was then awarded the 2016 Fashion Space Gallery Design Residency at LCF, which was the prompt for me to return to London. The commission of the Fashion Space Gallery was to produce an experimental project that would push the envelope of what we think fashion could be in its broadest context, which resulted in the realisation of the project; a collection of re-designed aspirations, Genetics Gym SS18.

The Validation Junky is your design-research studio project that explores new roles of technology in society, observing the vices of stripped-back human nature and imagining characters by exploring the potential of emerging human genetic and artificial intelligence technologies in fashion design and fashion photography. What is the intellectual process behind it?

I started The Validation Junky at the RCA in 2014. Today, it continues to inform, challenge and analyse all my commercial and conceptual outputs as a critical lens upon contemporary design, social behaviour, and commerce. ’The Validation Junky’ is a term from the book The Velvet Rage by Alan Downs, an American clinical psychologist.

In the book, Downs describes how anxiety from a young age can result in the subconscious need to prove and illustrate status later in life, especially affecting consumer motivation. This is particularly true for certain human attributes that cannot change, such as sexuality or ethnicity. Resulting human dynamics might include the strong desire to be associated with high-status brands, be ultra-masculine or feminine, or be very successful in a high-powered job.

This was a eureka moment for my thought process, and in many ways, explained many of my own motivations and perhaps why I was so interested in designing, conceiving and being associated with ‘beautiful’ objects in the first place. It gave me the incentive to consider what we might need to develop to form a strategic perspective that could underpin how we design products and why people want those products today.

The name ‘The Validation Junky’ became the label of what I was creating, imagining this one person who becomes a consumer archetype, which developed into a lens or filter to help me align myself to conceive design best today specific to the reality of today’s technology-integrated consumer.

Beyond the conversation on the fact that so many of the most popular consumer products today are bought because of subliminal context-specific meaning that becomes embedded within that particular object – such as the iPhone, a Louis Vuitton handbag, a RangeRover, a Rolex and so on – it starts to become essential for designers who might want to design something that matters socially and culturally – to build a psychological lens upon the design and what that designed object might mean within a wider social context.

In Genetics Gym SS18, epigenetics (in simplified terms, the study of biological mechanisms that will switch genes on and off) plays a central part in your project and is a discipline mainly only known by life scientists. Where did your interest in it come from?

I stumbled upon genetics through an ongoing conversation about what makes something aesthetically relevant and how you can make informed design decisions on aesthetic considerations within design development processes. This is highly relevant to products whose success rests upon subliminal social meaning rather than a utilitarian function, such as fashion, vehicle, and high-end product design.

The project loosely explores what could happen if you could design your body with genetics through either Epigenetics, CRISPR Cas9 or a still-to-be-invented genetic technology. Primarily, I wasn’t interested in the actual mechanics of the science of what is – and isn’t currently possible, but to use the general understanding of what genetic technology is capable of to create a critique or window on today’s consumer culture, asking why and how people might want to change themselves if it was possible.

After all, past a basic level of utility, such as keeping us warm or taking us from A to B, why we ‘want what we want’ is largely based on what a product ‘says’ or signals about your identity. Products illustrate subliminal information about your body and guide how people might ‘read’ you.

For example, when you sit inside a luxury car like a RangeRover and become connected to that machine as an extension of your limbs and body by touching the pedals, and steering wheel, you feel validated because the association to it ‘says’ a very specific statement about your context-specific illustration of genetic strength, in comparison to – say – a Ford Fiesta.

However, both objects have an overwhelmingly similar utilitarian purpose, to get you from A to B, and the extra functions of the RangeRover (ability to go off-road, carry 5 people in extreme comfort etc.) will most probably never be used.

What were the biggest technical challenges you faced in its development?

The first, and probably the biggest, technical challenge that I faced with this project was the ethical implication of suggesting that such a project could exist beyond a conceptual idea. Ethically, this is vast – potentially drastic. Therefore, finding an initial project strategy to become subjective to the topic both strategically and from an art direction perspective became paramount in developing the project.

The foundation of understanding how we might programme a machine to have the perception of genetic strength comes under very tricky territory because you come across the very uncomfortable challenge of having to define what ‘genetic strength’ is. Something everyone will naturally have a different perspective on; each perspective totally subjective and neither right nor wrong.

Secondly, the next technical challenge behind the project was finding models who were completely comfortable with their bodies and could grasp the fact that their edited faces and bodies could end up being used to discuss consumer culture and the future within potentially dystopian realms. The last thing I would want to do is to give any of them body dysmorphia disorder or anxieties, so I needed models who could understand what they were getting themselves into.

During approximately four months, I met a variety of models and chose a range of ethnicities, genders, body types, sexualities, tensions, and postures that I felt represented a good range of both cognitive hardwiring and genetic characteristics that could communicate different stories of anxiety and aspiration if a Genetics Gym product did exist.

Thirdly, whilst developing the project strategy, it was important also to consider how these bodies would work from an art direction perspective. I needed to develop a photo-realistic aesthetic so the viewer could connect and imagine themselves within the images, yet placed these forms as abstract objects so that you could clearly see that this wasn’t a proposal whilst reading aesthetically tight and considered.

I chose to remove all hair, including eyebrows, so that the model’s faces weren’t aesthetically re-proportioned, with all focus on the structure and form of bodies and faces. I worked with makeup artist Tamara James-Dickson and three amazing project assistants, Isabella Branca Gygax, Lara Gill and Dian-Jen Lin, to cover over all the model’s hair and eyebrows to create totally smooth, unified bodies, highlighting ethnicity and body type.

This team was then supplemented for a further two days by two genetic assistants, Ashley Campbell and Liane Stein; as directed by Dr Helen C. O’Neill UCL to discuss and label the feasibility of the genetic alterations that I was illustrating on a scale of 1 (impossible) to 5 (possible). The team backed up all 23 Genetic Gym menu ingredients, referencing scientific research papers, making it clear that some aspects of the project are scarily not a too far off real-world application, such as Sex Hormone Changes (probability 4/5), Fat Reduction (probability 3.5/5) and Ability to Put on Muscle Mass (probability 3.5/5), whilst others – are totally bonkers such as Instant Anti-Ageing (probability 0.5/5) and Neoteny / Cute Face (probability 1/5).

To build an atmosphere in the gallery, I sent sound-artist Timothy Wang (TWANG) a brief to respond to each five consumption strategies with abstract, mathematical sounds, building together into a 10-minute loop of five flavours, two minutes each, to play alongside the video installation of the bodies slowly morphing and changing. I needed the viewer to stand there and feel the dystopia and the complexity of why these people might go to such lengths to edit themselves.

And finally, as the project developed on, I started to question what it all meant. What am I learning, or what can be taken from a project like this; how does it strengthen or enhance the lens of The Validation Junky to better conceive commercial design for today? The prominent overtone that I take from this is that as we continue to develop technologies to integrate with so many elements of our lives, internet dating, social media, and online portfolios — it becomes apparent that technology is diminishing the colourfulness of human identity expression.

For example, Instagram celebrates a type of user that posts juicy and self-absorbed photos of themselves. The software celebrates a new form of human merit; like a big ass, being single, and apparently having a great time; and does not celebrate the old elements of human merit like intellectual capacity, good character, and actual skills. It becomes apparent that we need to find ways through technology to celebrate the range of humanity and who we are – rather than aspire to be something we’re not.

Dunne & Raby phrased this in their design manifesto, asking whether the design is ‘Change us to suit the world’ or ‘Change the world to suit us’. Perhaps someone could say that this type of thinking is anti-capitalist, as a lot of commerce and marketing is based upon aspiration and selling people the idea of a ‘better them / world’ through products. I would argue that with this kind of design thinking and the development of a critical lens through which you conceive design, it’s possible to design products and services within a commercial realm that celebrates identity, not diminish it.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

Maybe the best to answer this question is with the extremely powerful quote of my design hero, Zowie Broach of the Royal College of Art, “The most important thing is to be brave to your own truth.”

Rather than doing a job that already exists, I need to create the framework for a job before I’m able to start. This is the biggest challenge of not following a pre-set path but is perhaps a trophy of being at the forefront of my field. It would be easy to follow the existing rules of design and communication without much resistance.

Still, I’d like to think that what I’m working on will move society towards a future in which we totally control technology’s positive and negative consequences. The best type of art creates a window on what’s happening in the world right now. Whether you want to call this art, design or something else, calculated speculation holds the ability to sculpt and guide the conversation on how society operates now and in the future.

You couldn’t live without…

Dogs on Instagram make my day-to-day sweeter and become a nice counterbalance to all the topless self-affected bros that lure me around. With today’s technology come various pros and cons. Amongst all the cons that arise with an over-comparison culture, one of the strongest pros about the digital world and rapid communication is access to a whole load of dogs who have no idea what’s going on and want a nice scratch behind their ears.

Our love for dogs exists because they are like instant sugar that hits our brains. Having 24/7 phone access to dogs gives you instant serotonin and dopamine hits whenever you need it, the new cigarette break. I’m curating my feed into fewer show-offs and people having ‘forced fun’ into more poochies. Dogs know the secret to true happiness.