Interview by Lula Criado

Issues related to women’s reproductive health rights, like birth control and abortion, regardless of religion, culture or socioeconomic levels, are some of the most debated issues [by men]. Do you remember when US President Donald Trump signed an executive order to cut off all U.S. funding to international NGOs whose work includes abortion while surrounded by seven men? That happened in 2017 and was one of the points behind the intellectual process of Ani Liu’s project Grab them by the *: Mind controlled-spermatozoa.

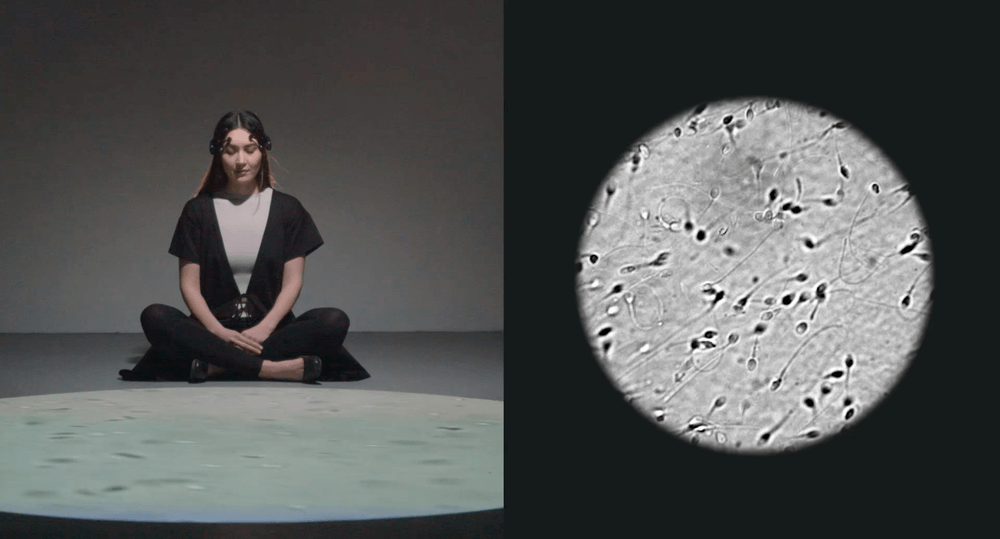

It is an intelligent and critical project that images a (dystopian or utopian?) future in which women using brain-computer interfaces would control the movement of sperm ‘with the agency of their thoughts’. Beyond its irony, Liu’s idea makes us reflect on how the sociological, cultural and scientific discourses around women’s reproductive choices are mainly driven by men excluding women from the debate.

Ani Liu is a transdisciplinary artist and speculative technologist. A recent graduate of MIT Media Lab (Boston, EEUU), Liu runs her studio. She designs multisensory experiences that, through technology, shed light on what it means to be human. For example, how do current technologies normalise cultural notions of surveillance? How will artificial intelligence affect our ethics? How do algorithms shape your beliefs?

In The Botany of Desire, done in collaboration with scientist Noam Prymes, Liu raises questions on interspecies empathy, exploring the relationships between humans and nature and the potential of biotechnology. ‘Where are the thresholds between science and its ability to change our emotional landscape? The speculative scenario involves plants, humans, lipsticks and a kiss. In it, a set of plants respond to emotions and grow and bloom when ‘touched by a kiss.

Liu’s work is a deep dive into emerging technologies’ social, emotional, cultural and ethical implications. Her statement lies in the concept of ‘plastic subjectivity’. There is no objective reality, as everything is embedded in our personal experiences.

In his book ‘Camera Lucida’ (1981), Roland Barthes writes about two concepts linked to reality: studium and punctum. The studium or interpretation [in his case of photography] denotes the cultural, linguistic and political interpretation. In contrast, the punctum indicates our personal experiences, the myths of our historical moment and the cultural background that make us establish a different relationship with the object [in the photography] or reality.

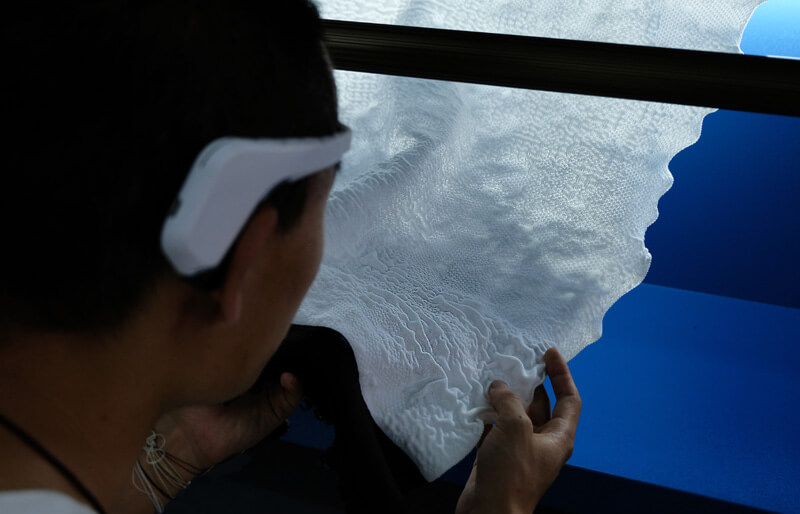

This shared philosophical linkage is evident in Mind in the Machine, included in the Queens Museum Biennial later this year. In the piece, Liu tells the story of a Chinese factory worker to raise awareness about the emotional consequences of technological advancements: mass production, anonymous labour, and automation. Via EEG signals, Liu translates into knitting the worker’s brain activity, creating a unique fabric that depends on the factory worker’s mental stress throughout the working day.

You are an artist and speculative technologist at the intersection of art and science. For those that are not familiar with your work, how and when did the fascination with them come about?

As an artist, I am fascinated by how things work and how systems come together. I’m often scattered in my thinking, but I find that it leads to exciting paths of learning. For instance, a few years back, I was building an IoT device with a camera. I became interested in how image capture sensors worked, which led me to wonder how the neurons in a brain perceive colour, and then how a neural net constructs its computer vision. It was a reasonably roundabout journey, but as an artist, I am interested in how piecing these disparate bits of knowledge together reveals deeper meanings of what it means to be human.

Your statement states, ‘With every technology and scientific development, our plastic subjectivity goes through modifications and expansions.’ Could you explain a bit more this idea of ‘plastic subjectivity’?

Many philosophers and theorists have spoken about this idea in different ways over time- the idea that there isn’t one genuinely objective “reality.” How we perceive our world is deeply affected by many elements of our time- our religion, culture, and technologies. Today, we often look to science and technology to inform us of objective truths, but it usually takes a cultural revolution for discoveries to be accepted.

For instance, when early astronomers first began observing that the movements of the planets revolved around the sun and not the Earth, despite hard evidence, Copernicus was condemned because of the radical way such an observation would challenge the authority of the church. Much later on in history, we see similar conflicts over the idea of evolution.

This is because scientific revolutions don’t just describe new information; as humans, they often alter societal norms and our sense of self. Technology does this just as radically but often more quietly. We often talk about the ways Facebook changed the way we socialise or how apps like Tinder shift our notions of intimacy— but there are also subtler forces at play, which I find interesting. How do current technologies normalize cultural notions of surveillance? How will artificial intelligence affect our ethics? How do algorithms shape your beliefs?

Emotions and behavioural responses are two central axes of your work. For example, in The Botany of Desire, you explore the use of science for emotional ends. Could you tell us the intellectual process behind these projects?

Making art has always been investigating what it means to be human. It allows us to access other bits of intelligence- emotional, intuitive, subliminal– that create an essential dialogue with those of reason and logic. Don’t misunderstand me when I say that- I deeply believe in the scientific method— but I think there are many non-linear channels through which reality is gleaned. While science allows us to know and measure the world, art allows us to reflect on how we feel about it. For me, the two are profoundly entangled and co-inform with each other.

One of your latest projects is mind-controlled spermatozoa, in which, through the use of a brain-computer interface, she controls the movement of sperm with the agency of her thoughts. In which ways do you think are interactive and digital technologies changing or affecting human behaviour?

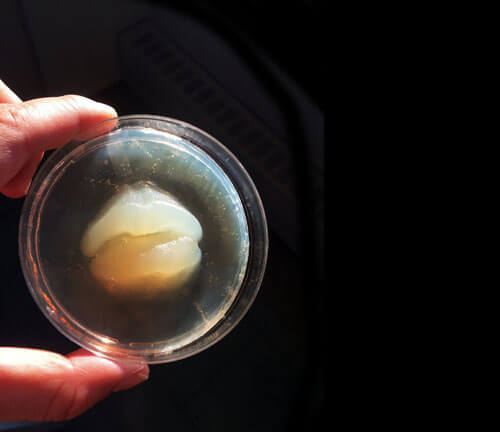

With Grab them by the *, I created a device to control sperm to spark a conversation about the many cultural and scientific discourses that shape the notions of the female body. Artistically, this piece creates an act of female empowerment, responding to the current political regimes in which women are losing rights related to procreation within their bodies. Investigating the body as a medium of culture, this project raises questions as to how we operate in our politically gendered landscape.

Navigating the divergent connections between art and science, this work challenges the viewer to question what is possible. Whereas our biological understanding of sperm is usually deterministic (i.e., as an inherent homing device racing towards the chemical signatures of an egg) or coloured by gendered cultural constructs (i.e., its semiotic use in pornography), this project seeks to invert all preconceived notions.

By creating a work that is simultaneously technological, functional, and symbolically potent, it seeks to expand our notions of what is possible and what is possible to question. Moreover, I think many technologies are changing our behaviour profoundly and deeply unknowable ways. In this piece, I sought to meditate on some of these aspects about gender deeply.

What directions do you see taking your work into?

Over the last few years, I have become extremely interested in smell as a sensory conduit of knowledge. I have made many perfumes in the studio and feel excited to continue with those experiments. Last month, I was lucky enough to go on a zero-gravity flight, and recently finished Elon Musk’s biography, so space exploration has been on my mind a lot too.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

Fear. Procrastination. Perfectionism.

You couldn’t live without…

Sriracha.