Words by Lula Criado

My first exposure to the creative universe of Anna Dumitriu was when I read a piece about her work in The Guardian. Her work caught my immediate attention, thanks to my background in Molecular Biology and Genetics. Even though the intersection between art with science is nothing new, Brighton-based bioartist Anna Dumitriu encompasses an innovative approach to both.

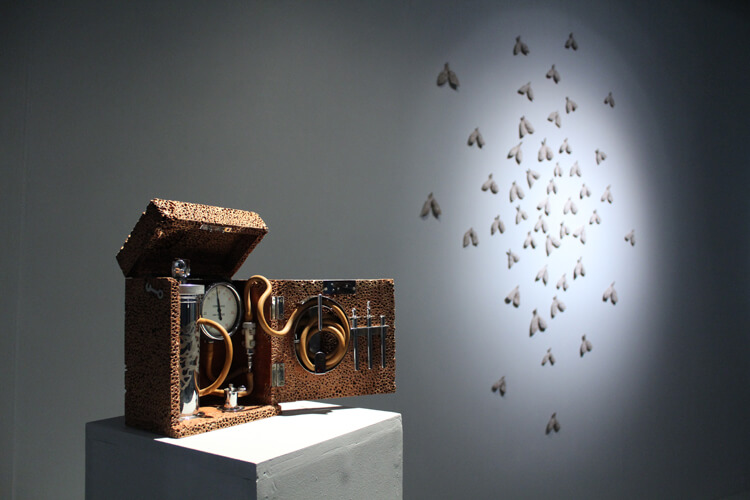

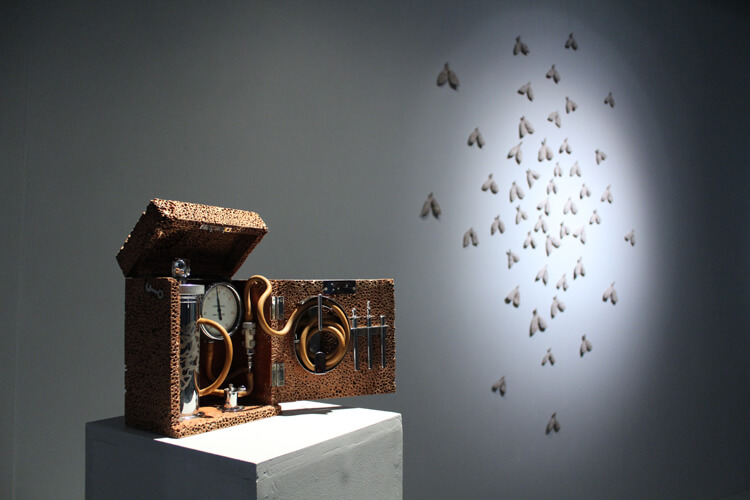

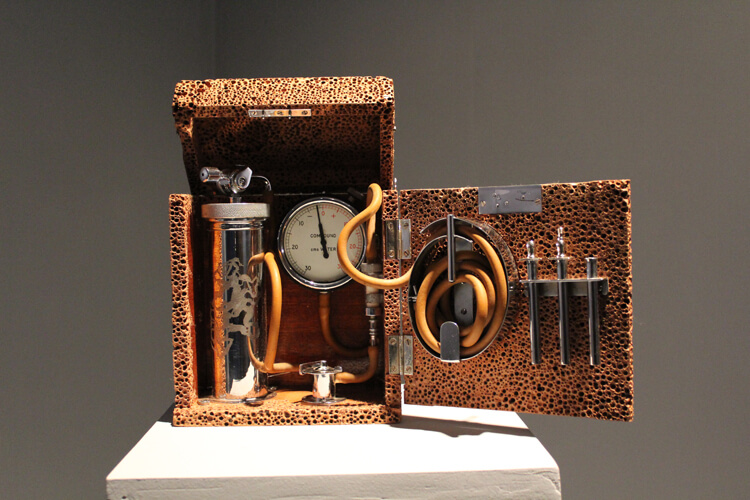

From a philosophical angle and in using a combination of emerging technologies, textiles, altered historic objects and biological matter as artistic mediums, Anna Dumitriu investigates how the world is involved with science and helps us understand deeper medical issues like allergies —The Sensitive Project—, bacteria —Cybernetic Bacteria— or contagion —Vienna Underground/The Third Woman—.

The Sensitive Project is a project that covers allergies—how they work and which effects they have. Cybernetic Bacteria is a thought-provoking performance made in 2009 in which Anna Dumitriu blends philosophical notions of the sublime with bacterial communication to compare human communication to bacteria. The purpose of Vienna Underground/The Third Woman is to draw attention to the history of the Plague in Vienna.

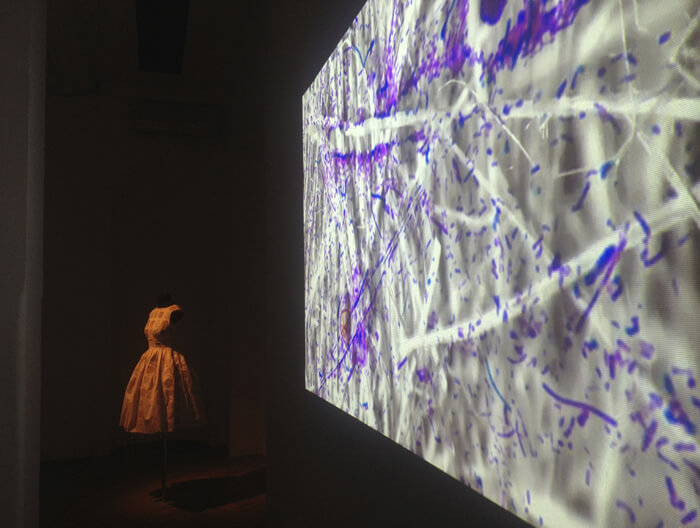

Her last project The Romantic Disease: An Artistic Investigation of Tuberculosis is a project that commands the viewer’s attention, focusing it on tuberculosis, a disease clinically unknown until 1882 when Robert Koch identified Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Interestingly, tuberculosis was considered during the early 19th century a fashionable disease by Romantic poets and writers.

The project —involving workshops and an exhibition— is a journey through the history of humanity’s relationship with tuberculosis: From superstitions to genetic analysis of bacteria.

Your work is at the forefront of art and science collaboration, when and how did the fascination with bacteria and living biological structures come about?

I think I’ve always found bacteria fascinating since I first found out about them as a child, and the more I find out the more intrigued I become. About ten years ago I started an ongoing collaboration with microbiologist Dr John Paul to take this fascination further and things have progressed from there.

In the earliest stages of my work, I was intrigued by normal flora bacteria, the ubiquitous bacteria that live on us, in us, and around us. At the time this area was described as being of no commercial or medical interest – an ideal area for artistic research some might say! It threw into question for me the ways in which our scientific understanding of the world is limited by mundane things like finance, and how the limits of our understanding are drawn by factors other than curiosity.

Dr Paul has a long interest in the natural history of bacteria and was also keen to be led by a curiosity for this work, which opened up a way of communicating microbiology to the public. The project was originally funded by Arts Council England rather than a scientific research body and seemed to indicate new possibilities for collaboration. Since the advent of whole-genome sequencing of bacteria and other technological developments that enable us to understand these microbes far better, this area of research has now become known as the microbiome and there is a kind of ‘gold rush’ to find innovative new uses for previously undiscovered bacteria or bacterial properties.

My work has co-evolved with technology and my learning of microbiological techniques and I have become more interested in clinical microbiology and the issues affecting modern healthcare.

Is BioArt blurring the boundaries between scientific research and creative expression to make scientific research more accessible to the public?

I would like to think that at least in some ways it is, at least in what I am trying to do. I think that it is important for the wider public to have the tools to participate in debates around new technologies in biomedicine and not simply to be controlled by scare stories in the media (the British Press is particularly notorious). For me, conversation, dialogue and participation are important elements of my practice and alongside my exhibitions, I aim to create hands-on opportunities for people to get involved that are suitable for all ages, from young children who have not thought about bacteria or antibiotics before to older people who have concerns around things like hospital ‘superbugs’ or who have experiences of the world before antibiotic medicines and fascinating stories to tell.

What are the biggest challenges of BioArt?

Bioart by its very nature means that living systems are somehow involved in the production of the work. There are debates on whether the work has to be alive when it is exhibited or not, and I would see this as more of a performance element of the work rather than a requirement.

In the case of working with pathogenic bacteria, I need to be sure the work is completely safe, either fully sterilised prior to the exhibition, or securely contained somehow. Working with a living medium has its own problems such as paying attention to ethical and health and safety issues or just keeping it alive and getting it to do something you want it to do. I am talking broadly here and not just about work with bacteria – bioart can also involve living creatures or tissue cultures.

The Romantic Disease: An Artistic Investigation of Tuberculosis is a subjective and emotional exploration of the romantic disease. However, it is an extremely contagious disease and the second leading cause of death. What are the possibilities and limitations of using living structures for artistic proposals?

I often talk about how it is necessary to develop a bacteriocentric view of the world, an idea raised by Betsy Dexter Dyer in her book “A Field Guide to Bacteria”. This means being able to understand the world from a bacterial perspective, to think about their wants and needs. When you can do that it is easier to understand what might be possible.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (TB) is a containment level 3 organism, so needs a very secure lab to work with live samples. I have had some training to work in such a setting but I always work with experienced scientists too. It’s not possible to take live TB outside the lab so I work with it in there and only use sterilised samples in my work. In the “Romantic Disease” I used the extracted DNA of killed TB, which has been proven to be safe for such use. In fact, the technique is a recently validated protocol used for whole-genome sequencing of TB in the research of the Modernising Medical Microbiology Project, where I am an artist in residence.

It is a collaboration between Oxford University and Public Health England. Their project is to look at the implementation of whole-genome sequencing of bacteria in healthcare settings this will be a revolution in microbiology and infection control. I like the idea that the work has been tainted by the disease, but it has to be completely safe for the audience.

How do you think artists and scientists can best maintain ethics when working together?

Through discussion and dialogue. By trying to understand each other’s points of view and needs and working out how to best meet them. Ethical issues in such a context are related to institutional reputations, PR, health and safety and the law. Where a true ethical debate comes into play is where there are conflicting views and there is no clear or obvious direction to take. I have written a book on this, which will be coming out later in the year (see www.artscienceethics.com for more information).

For scientists, one area of ethical concern is how to dispose of the living tissue at the end of an experiment. How do you cope with the living tissue at the end of an exhibition?

I use the same methods and work in collaboration with scientists to do it – everything is sterilised. In my case, I am working with bacteria rather than animal or human tissue so it doesn’t raise so many ethical issues around the actual disposal of the organisms, beyond the health and safety issues.

You couldn’t live without…

Bacteria. In fact, none of us could. They are an integral part of our digestive system and our immune system and help perform many processes in the human body. They also help create the Earth’s atmosphere. As an artist, their complexity, their strangeness and how they affect us is a huge inspiration for me.

One for the road… If you had the choice of being born in any period throughout history, which period would you choose?

I think I’d like to be born in the future (after the invention of time travel), be vaccinated against the Plague (a vaccine is available now) and travel back in back in time to the Great Plague of 1665 in London, I’d have loved to sit in a coffee house with Samuel Pepys and discuss the problems of the day (I would also need to pretend to be a man to do this) such as the lack of fine textiles for his fashions (the disease travelled the world on exotic fabrics).

I’d be fascinated to learn about how word of the Plague spread and how the media of the day reported it. I would also be fascinated to visit the so-called “plague village” of Eyam in Derbyshire and understand what went on there with their self imposed quarantine. I’ve read so many books about that time, to see it for myself, from a position of relative safety, would be sublime.