Interview by Daniela Silva

Egyptian-born artist Basim Magdy has gained recognition for his film, photography, and text work. With a style that blends the everyday with the surreal, his art challenges traditional narratives and invites viewers to reconsider their perceptions of memory, history, and time. His work often questions the stories we are told and those we tell ourselves, shedding light on the overlooked or forgotten aspects of life. Magdy’s artistic journey began in Egypt, where he was exposed to traditional and contemporary influences. His curiosity about the complexities of history and the ways it is shaped by power and storytelling fueled his creative practice. From an early stage in his career, Magdy has been committed to pushing boundaries regarding his chosen media and the themes he explores.

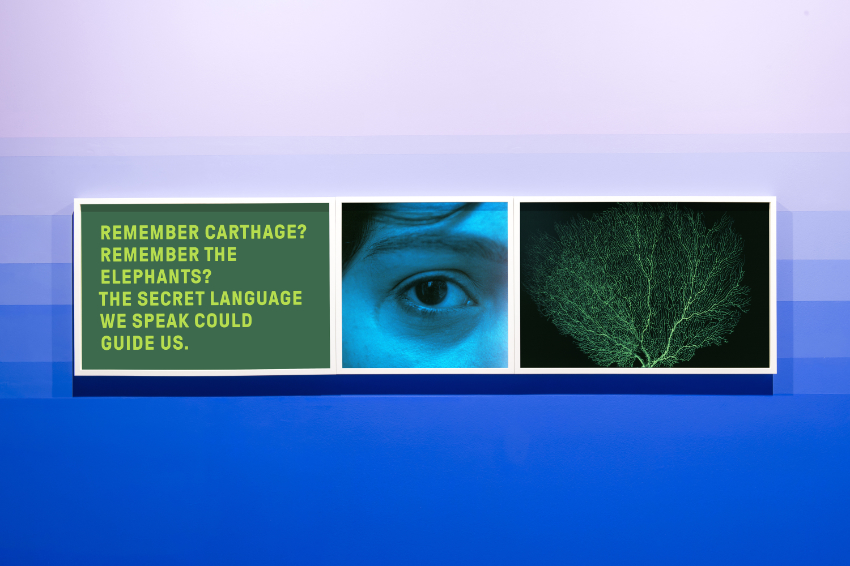

A recurring theme in Magdy’s work is memory, which he sees as a retelling of the past through the lens of the present. For him, history is rarely an accurate reflection of events; instead, it is shaped by those who have the power to tell the story. His photographic series Someone Tried to Lock up Time exemplifies this concept, creating imagined histories for the countless individuals whose stories have been lost over time. The series highlights the fleeting nature of personal narratives and the broader implications of historical erasure.

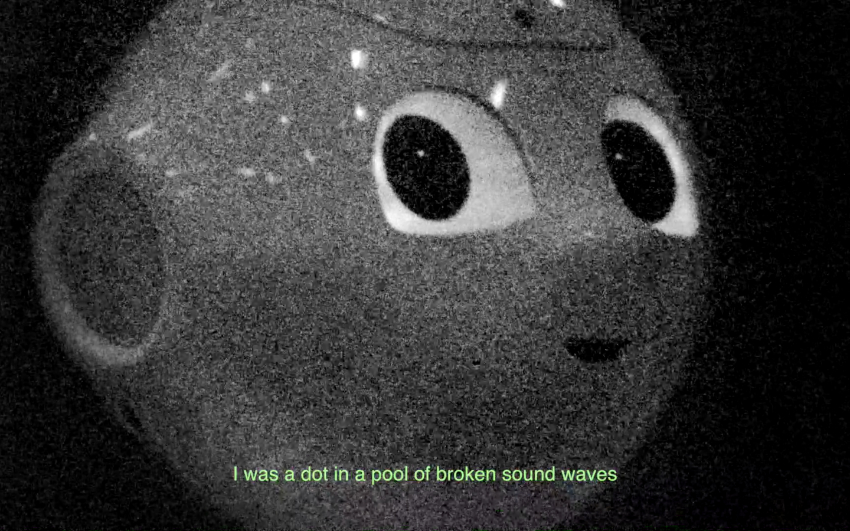

Magdy also blurs the line between reality and fiction. He draws from the logic of the real world but overlays it with layers of absurdity and randomness that often go unnoticed. This approach encourages viewers to look beyond the surface and engage with deeper questions about the structures of reality and the stories built within it. His films are marked by experimental techniques that create striking visual effects. Basim manipulates film material through processes like chemical alterations and double exposures, using the medium to uncover hidden dimensions of reality. Combined with poetic storytelling, these techniques give his films a unique aesthetic that challenges conventional narrative forms.

In his 2018 film The Dent, Magdy explores themes of collective ambition, failure, and identity through the fictional tale of a small town vying to host the Olympics. The story unfolds unexpectedly, capturing the complexities of human behaviour and the fragile balance between hope and disillusionment. Magdy’s artistic path is driven by curiosity, experimentation, and a deep engagement with the world around him. This encourages viewers to embrace uncertainty, question established narratives, and explore alternative ways of seeing and understanding the world.

Your work often delves into themes of the unconscious and memory. How do these concepts influence your creative process, particularly in your films and photographic series?

It’s impossible to separate memory from the present. I see memory as the retelling of the past through the circumstances of the present that create the urge for this retelling. For years, I’ve been concerned with making work questioning how history is constructed, recorded and recalled. I strongly believe history is rarely what happened; it’s how the story is manipulated by the ones telling it. I think my films are always about the present. Sometimes, I’m looking at the present through the ambiguity of the past and the imperfection of memory. Sometimes, it’s the present, as I imagine it will be seen when I look back at an imagined future.

The passing of time is the most political subject one can work with because it encompasses everything. It shows us where we went wrong and how to not fall for romanticising our future as science fiction. In 2018 I started working on an ongoing photographic series called Someone Tried to Lock up Time. The idea was to create a fictional history of as many of the billions of people who lived and died since the beginning of time without having their stories told. After all, history is written by two groups: the victors who eliminated the ones who could tell the story differently and those who could write. This series is a mere gesture, an attempt to highlight the impossibility of anything other than eventual disappearance in time.

You frequently blur the lines between reality and fiction in your work. What draws you to this interplay, and how do you navigate it within your digital pieces?

I make fiction rooted in reality. It’s based on the logic, appearance, and structure of reality. Reality’s most intriguing aspect is its layers, which often go unnoticed or are intentionally overlooked. When I started paying attention, I realised that every day of my life included a significant amount of randomness and absurdity. I frequently eliminated or ignored those occurrences to make sense of my reality.

This is standard practice; others cope with what they don’t understand or can’t control by laughing at it. Those layers of absurdity and randomness within reality are often dismissed. This is precisely the starting point of my depiction of reality as fiction. This practice is more common in writing history and its perception and consumption. History is expected to make sense as a series of coherent stories. We are told to learn lessons from the past, its victories and its defeats.

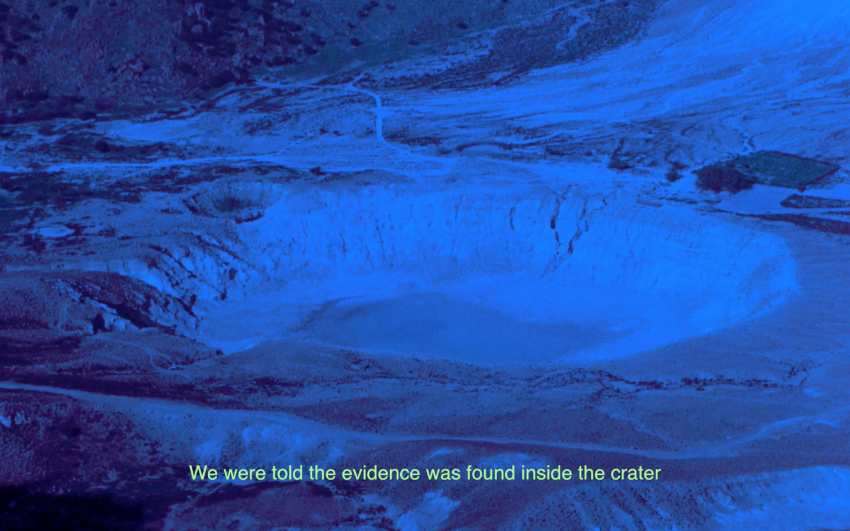

I’m more interested in asking questions about things that don’t have logical answers. For example, when Hannibal almost invaded Rome with an army of elephants, where did he bring the elephants from? The Sahara would have been too big and hot for them to cross without a constant water supply, and India was way too far, and most of what was in between was under the control of the Roman Empire. In my film M.A.G.N.E.T (2019), I created an extremely unrealistic fictional narrative. The film starts as the world grapples with a new reality: gravity is getting stronger.

This affects everything from walking to growing plants to the stock market. Instead of making a film about what that meant for us, I chose another route: I made a film about the existence of misinterpreted ancient artefacts that record the same occurrence in ancient history. MAAT commissioned the film for a solo show in Lisbon. The show was cut short when a storm destroyed a part of the building, and the museum had to be shut down for renovation. A few months later, the whole world shut down when we were all confronted with the unexpected: a pandemic that took millions of lives we were not ready to lose. This is the reality I make fiction about.

Many of your pieces combine text with imagery. How do you balance these elements to enhance the storytelling in your films and photographs?

I used to write poetry in my late teens and early twenties but stopped when I accepted something was clearly missing. When I started making films a decade later, I realised that a poem can be a film. I began writing scripts poetically, and everything started falling into place. It became evident that when I was younger, I was more focused on the meanings of words than creating meaning with words. I use text in my work, whether film or photography, not to explain an image or translate it into words. Text, for me, is part of a composition. It’s only there to help me say something without actually saying it.

Your films are known for their experimental techniques and unique visual language. Could you share some insights into the processes and technologies you employ to achieve this distinct aesthetic?

All my work with film is better experienced as expanded cinema and expanded photography. I became interested in film as a material because of its ability to create a visually different representation of reality. While the film’s main purpose may have been to create an image of reality, for me, it’s a tool to highlight what may be hidden within reality and take it in all the directions my imagination can explore.

Technically, I have pickled film in acidic household chemicals, punched holes, double-exposed it and experimented with analogue editing. These processes are fascinating, but they are only effective when used as tools to communicate something meaningful. Experimenting with film to push it to do what it wasn’t made to do is extremely rewarding; it’s like entering a world that no one has seen before. It feeds my curiosity and keeps me intrigued about what can be done next.

Your work often experiments with unconventional formats and interdisciplinary approaches. How do these choices shape how your audience engages with your art, and what impact do you hope to achieve through these innovations?

When I started making films, I promised myself to add at least one new element to each film I made. Filmmaking offers me an incredible amount of freedom and space to experiment. As much as I love experimenting with sound, image and narrative and the many ways of layering them together, I’m also invested in exploring the possibilities of creating a sense of time-based painting with film. When I made my film FEARDEATHLOVEDEATH (2022), I was aware of the impossibility of tackling death as a subject with any kind of logic. I ended up making what I think of as my most experimental film. For things to not get too abstract, I divided it into chapters: a dead person’s room, a time-based abstract painting in the style of Stan Brakhage, a love poem, and an alligator looking down from the clouds.

I never have expectations for how I want an audience to engage with my work. There is no audience. We all experience art in many forms, including our personal experiences, feelings, logic, and understanding of the world around us. This makes engagement a very individual experience. But generally speaking, I’m happy if someone feels something—anything—while experiencing my work.

Colour and light play significant roles in your photographs and films. How do you approach these elements to convey specific emotions or narratives?

Light is how we perceive the world around us. Without light, there are no colours, shapes or objects. Without light, we become invisible in an invisible world. One of the things that fascinates me about working with film is that it doesn’t matter what you shoot and what stories you tell with your film; in the end, what brings it to life is the poetic journey that light travels from the lens of a projector to a flat surface.

This humble act of projecting a film is what makes it real. In my films, I use colour filters a lot. I also pickle the rolls of film I shoot my photographic works on to create bright, saturated colours. This act of altering the colours of reality is meant to separate it from its representation distinctly. You can recognise what you see; it’s familiar, but the shift in colour makes it otherworldly. It announces its new existence as a fictional entity based on reality. This opens doors for imagining and proposing alternatives in many directions.

In your film The Dent, you narrate a fictional story of a small town’s futile bid to host the Olympics, reflecting on collective failure and hopefulness. How does this work explore the concepts of utopia and dystopia, and what messages are you aiming to communicate through this narrative?

The Dent is an essential film for me. It took two years to make, and I filmed it in many countries and locations. I wasn’t particularly concerned with utopia and dystopia; I’m much more interested in what happens between defined extremes. That’s where life that defies definition happens. The Dent is about the space within the unexpectedness.

When the inhabitants of a small town party all night and, as a result, miss the chance to pitch their bid to host the Olympics, they become even more deluded by their desperation for recognition. They get scammed by a travelling salesman who sells them concrete mixers disguised as dinosaur eggs. When the truth is exposed, and the spectacle is shattered, the mayor decides to hypnotise them with forgetfulness by bringing the circus to town. At this point, a parallel story evolves from the narrative when the circus owner has a wild dream. The next day, the circus elephant finds itself transforming into a zebra. It decides to take matters into its own hands as the town’s inhabitants accept their failure and start re-enacting the lives of their ancestors.

The three central characters in the film are the mayor, the circus owner, and the elephant. Their actions control the flow of events, but the film becomes about the town and its inhabitants. The Dent is mostly about power and politics and their influence on collective delusion.

What’s your chief enemy of creativity?

A life where nothing happens, where repetition and unrealistically excessive comfort define the passing of time. If any society or individual starts seeing this as the ultimate goal and gets even close to accomplishing it, the end is near. Without unexpected experiences, there is no progress. Without progress, there is no evolution. Without evolution, there is no survival.

You couldn’t live without…

Curiosity and empathy.