Interview by Tina Gorjanc

Firstly born in Querétaro, Mexico, in 1991 and reborn again in 2017, Felipe Osornio is the only performance artist with three kidneys. Working under the artistic name Lechedevirgen Trimegisto, a pseudonym that takes its meaning directly from the alchemical tradition, the visual artist specialises in performances that focus on topics such as the body, disease, and death.

Previously, his work has been linked to post-pornography and Latin American queer art, as well as Mexican mysticism and folklore. However, after the transplantation surgery that saved his life which has been significantly hindered for the last 10 years due to kidney failure, Osornio started to use art as a tool for healing and space for understanding deep transformations of the biological self. After completing a master’s degree in contemporary art and visual culture as well as a degree in visual arts from the Faculty of Fine Arts, UAQ, Osornio became a member of the Thematic Network of Transdisciplinary Studies of the Body and Corporealities “Cuerpo en Red” of CONACYT.

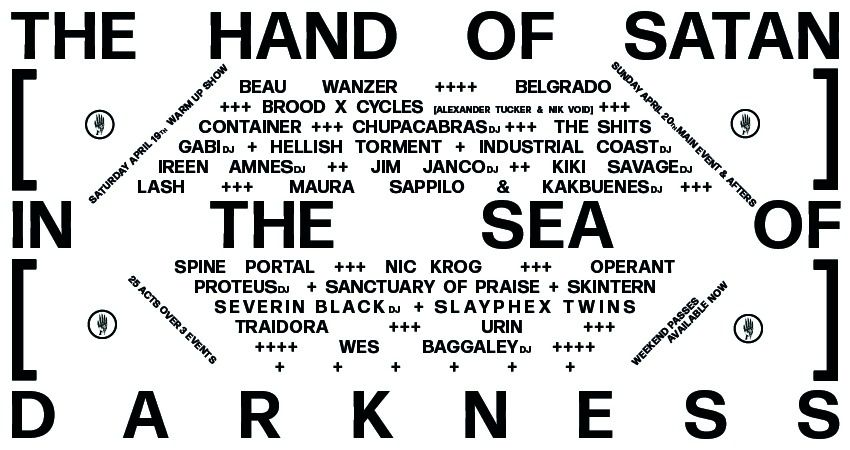

Lechedevirgen Trimegisto’s most recent work focuses on developing a series of contemporary art projects that reflect on the union of science, art and medical rituals. His newest performance, Organolepsia, addresses the social problems that arise from the donation and trafficking of organs in the modern Mexican context. With this piece, Lechedevirgen Trimegisto seeks to use art as a way for collective awareness in order to expand the information and make visible the bioethical, cultural, economic and political mechanisms that are involved in the practice of transplantations.

Even though Lechedevirgen Trimegisto’s body of work covers a vast variety of topics ranging from medical folklore to current cultural issues, the common denominator of his portfolio seems to be the gesture of seeking help from his public to combat the misinformation and panic that impede organ donation which encourages trafficking through illegal procedures in which donors put their lives at risk by performing surgeries in inappropriate conditions.

In your performative practice, your body is your artistic medium. How do you feel being the artist and, at the same time, the artistic medium?

When your own body becomes the medium to materialize an artistic project, the distance between the artist and artistic work disappears, the same distance that defined for centuries the visual artist as a producer of auratic, contemplative, beautiful objects, etc. Throughout artistic expressions such as action art, performance art, body art or bioart that propose the body as its epicenter, you can generate another type of knowledge and more extensive or complex connections because they imply the idea of art as a way of doing and not as something that is done.

My artistic work considers the physiological, pharmacological, surgical, emotional, immaterial and invisible changes that occur in my body, but also the social, cultural and political implications that surround it. Put in another way: our body is always crossed by life and death, a paradox practically impossible to decrypt. I think that this is the most honest way in which I can create art because when you work directly in your own body, you not only open a window to an intimate and vulnerable space, but you also touch key aspects of human existence.

In this sense, what has been your most challenging project so far?

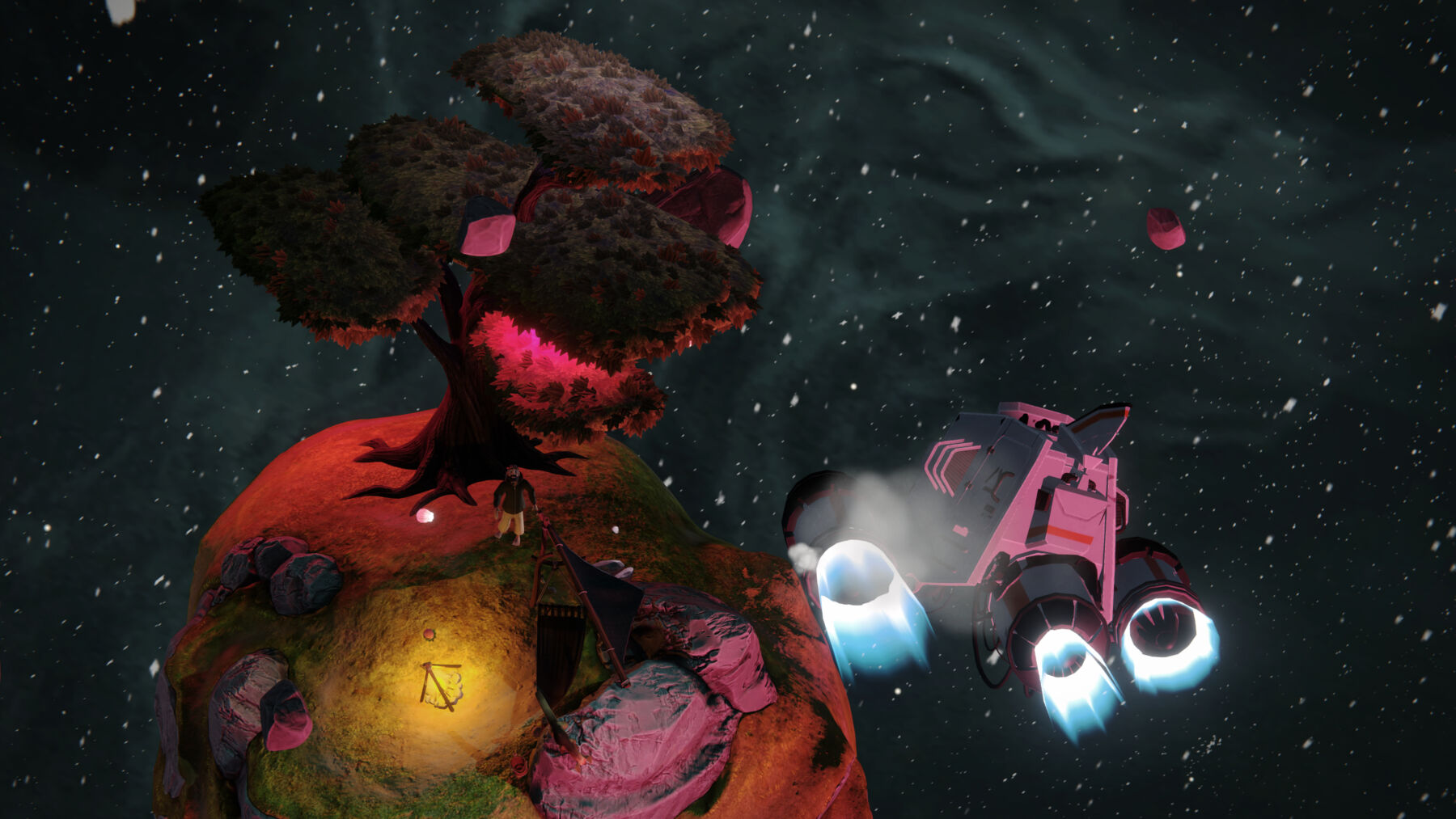

The riskiest and most complex projects that I have carried out are directly connected with my own mortality and, therefore, with the relationship I held with my own body as a territory invaded by disease. In 2016 I started with the project called The Blood Tree, the purpose of my experience when faced with hemodialysis1. Interested in using my body as an artistic medium to talk about renal insufficiency and about corporeal and physiological manifestations, as as the emotional and mental ones which are caused by therapy.

Since, at that moment, I was in what medical science calls the terminal stage, The Tree of Blood could have been my last artistic project; in that way, it becomes an art piece/documentary video that works as a sort of ultimate portrayal of the experience on the edge.

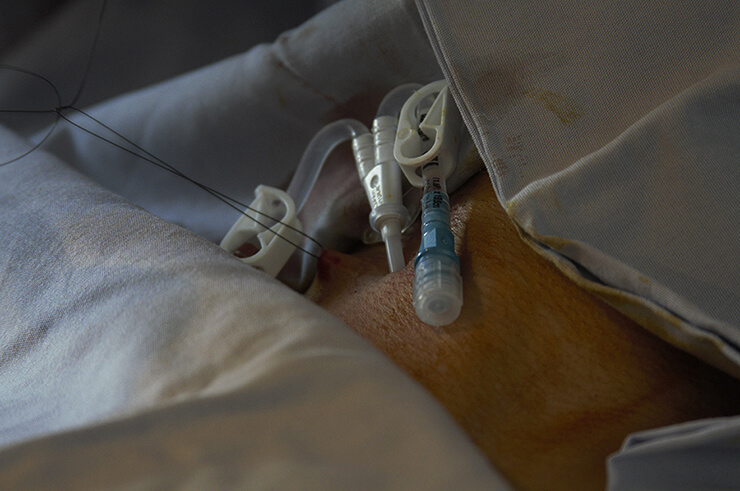

The project started as a text I wrote during the hemodialysis sessions, trying to capture the effects that were produced inside me by staying connected to a machine that drained all the blood from my body through a catheter inserted into the jugular vein a few centimetres away from my heart. Subsequently, the project became a videoperformance that portrays the reading of the text during one of the hemodialysis sessions.

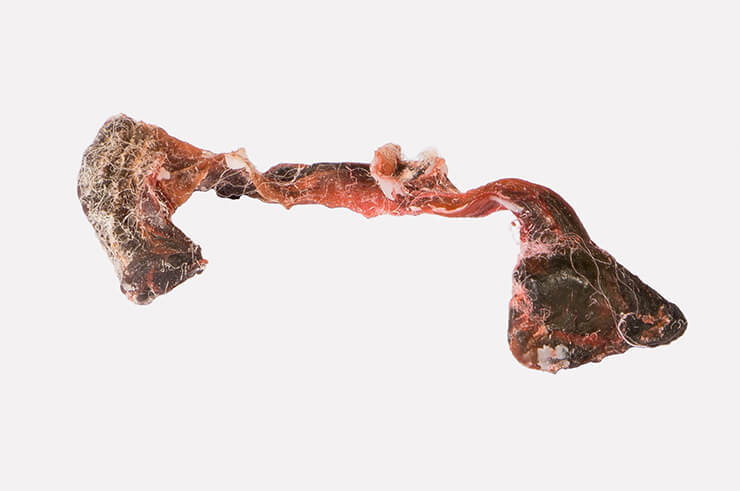

In 2018, after the kidney transplant that keeps me alive now, I performed Antibody, an artistic project that had as its starting point the treatment with immunosuppressive drugs that the transplanted people are conditioned to take for the rest of their lives to avoid the rejection of the organ or transplanted tissue.

Through the taking of samples of tissue and fluids (skin, blood, faeces, and saliva), the search, collection, and cultivation of opportunistic pathogenic bacteria present in the microbiota of my own body were carried out. The culture process produced a total of eight bacteriological strains that could potentially kill me. The act of making visible the invisible, of materializing or “making appear” these potential murderers implied one of the biggest risks in my career, while it revealed the fragile line between life and death when the difference between well-being and disease lies solely in the number of bacteria.

1 Type of substitute therapy for people with End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD). Because the ESRD has no cure, hemodialysis is only a maintenance therapy, whose sessions can last between 3 and 4 hours and must be performed 3 times a week.

With the term ‘body without organs, ‘ Deleuze describes a relationship to one’s literal body as an abstraction of corporeality. What is your relationship to your body after the transplant? Has it had any influence on the way you perceive your body?

Probably for Deleuze, organ transplantation would be understood as a tool of reconfiguration / disorganisation of the body, a form of multiplicity, addition or growth, while for philosophers like Jean-Luc Nancy, the transplanted organ would be understood as an intruder, a “foreigner” unable to naturalize, always with the possibility of leaving, exiting, rejecting.

In my case, it not only changed the way I perceive my body, but it changed the way I perceive the world and life itself. The transplant meant a rebirth, a way of being reborn and learning to live again. March 28 2017, was the date on which the transplant was carried out, and it is also the date of my second birth, not only because the illness that was ending with me came to an end but because my life changed completely, from my diet to my artistic work mutated into something completely new.

Since my own mother was my donor, far from understanding that kidney as an intruder to my body, I understand it as an immaterial connection between mother and child, like an umbilical cord. We explored this concept together in the performance Lifespan on the first anniversary of my transplant and the first collaboration between my mother and me in the performance field. Even in that performance, I ate the last fragment of my own umbilical cord in order to reaffirm my new birth.

Now I perceive my body as a conduit between the living and the dead, between the material and immaterial. Perhaps it would be interesting to think of the transplanted body as a ‘body without organs’ (BwO). After all, I have three kidneys.

Disease, body, and death are deeply rooted in Mexican culture (and in your practice), and you have stated that in the past, your work was connected to mysticism and Mexican folklore. Now you are more interested in the relationship between the immaterial and the material. Could you please expand more on this? How has your evolution as an artist been?

I am 27 years old, 10 of which I was sick and 10 of which I was doing performance art mainly. I started doing performance art in 2009, and during these 10 years, my artistic work has been composed of a wide range of interests, motivations, and approaches, including sexuality, gender studies, queer theory, post pornography, homophobia, violence, witchcraft, radical spirituality such as fideism2, popular Mexican culture, and recently the crossing between science and art.

Interestingly, the kidney disease that would lead to transplantation also appeared 10 years ago and during that decade, when my artistic work was evolving, so did the disease. At a certain point, both scenarios crossed and gave a pattern to the artistic work I do today.

My interest between the material and the immaterial comes from the beginning of my career, when I interpreted the figure of the artist as a medium capable of channelling and materializing the artistic phenomenon, which is why my artistic name (Lechedevirgen Trimegisto) refers to the father of alchemy (Hermes Trimegisto) and the messenger of the gods (Hermes/Mercury).

I used to believe that art and magic were the same things, but the difference is that the “magic” to which art brings you closer to is the magic of life itself. Contrary to what one would think, alchemy occurs before our eyes all the time, but we do not see it. We are not aware of it. Art helps you see. I believe that artists are here to remind the world that it is dying and, therefore, it is alive.

2 Cult of José de Jesús Síntora Constatino, saint of the town of Espinazo, Nuevo León in northern Mexico, who became popular in the 1930s for performing miracles and for his unconventional healing abilities and methods.

What directions do you see taking your work into?

I do not know. Although I am currently focused on minimalist profile works that involve the combination of art and medicine, art and technology, bioart or biomedia, I still cannot get rid of my baroque past in which everything takes the form of dioramas, tableaux vivant or variety shows.

I find myself in a very intense inner search moment, trying to find the right dose between these two components in order to create artistic works that are increasingly powerful, complete, and round. Issues such as organ donation, transplants, and disease are likely to continue to be the guidelines of my next work, but anything can happen.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

I think that the main enemy of creativity is doubting yourself. Self-sabotage is one of the most common reasons why creativity can evaporate. Beginning to doubt your own ideas, denying your intuition or your own hunches in a creative process leads to the loss of freedom, creating imaginary barriers that asphyxiate the artist, and there can be no creativity without freedom.

The artist must act without limitations. The greatest creative act is the one which is carried out from a space of freedom, free from prejudices and doubts. Perhaps that is why I never adjusted to the framework of conventional arts. Also, festivals, museums, and galleries restrictions and censorship are a real turn-off.

You could not live without …

My first answer should be “a kidney”, but I’m going with Art.