Text by so-far & CLOT Magazine

TikTok, the video-sharing social network is being excessively more popular within the tedium of home quarantine1. A radical virtuality has been borne out of both necessity and boredom, and it has permeated every individual user, of every generation, in every corner of the globe under lockdown and with access to data-streaming networks. Confined in our matchbox apartments, we huddle into our apps, recording home-cooked meals, dance moves, yoga routines, standing #WFH desks. If not for social networks and live-streaming, would we have otherwise gone absolutely insane?

Many interdisciplinary artists have anticipated and articulated this transition into the virtual realm, though none could have foreseen it would be under such duress, under such painful circumstances, and with such a drastic renouncing of physical sociality. Now, CLOT Magazine and so-far revisit a collaborative dialogue that was initiated last November, before any of this began and COVID-19 pushed humans nearly entirely out of public space and onto digital platforms.

Our online publications have brought together two very similar artists within our respective networks: Rosana Antolí and Teow Yue Han. Their invigorating work breaks down barriers between the fields of dance, choreography, performance and new media, sculpture and installation. Although the comparative conversation tangos between their discrete practices, read in the light of our current state of affairs, it now implicates issues we must openly address as we wade through a season of increased digitalisation. What are we exposing ourselves to as we communicate on Zoom2? To whom are we surrendering our data for contact tracing? How is the state monitoring crowd density3?

And further — offline — how can we reconsider our movement and relations within public space as charged (to use that term Rosana applies to gestures) with much more than we previously assumed? Gia Kourlas, dance critic for the New York Times, writes on the choreography of safe distancing: When you walk outside, you are responsible for more than just yourself. We are in this together, and movement has morals and consequences — its own choreographic score, or set of instructions — in this age of the coronavirus4.

How can we move, now, mindfully? In and out of the pandemic, these are the questions that these two artists concerned with technology and movement have always been asking. And we, the editors of so-far and CLOT Magazine, believe that these queries can initiate a richer, more nuanced awareness of both our virtual and physical selves, as we move, eat, swipe, dance, and scan.

We are in this together, and movement has morals and consequences — its own choreographic score, or set of instructions — in this age of the coronavirus.

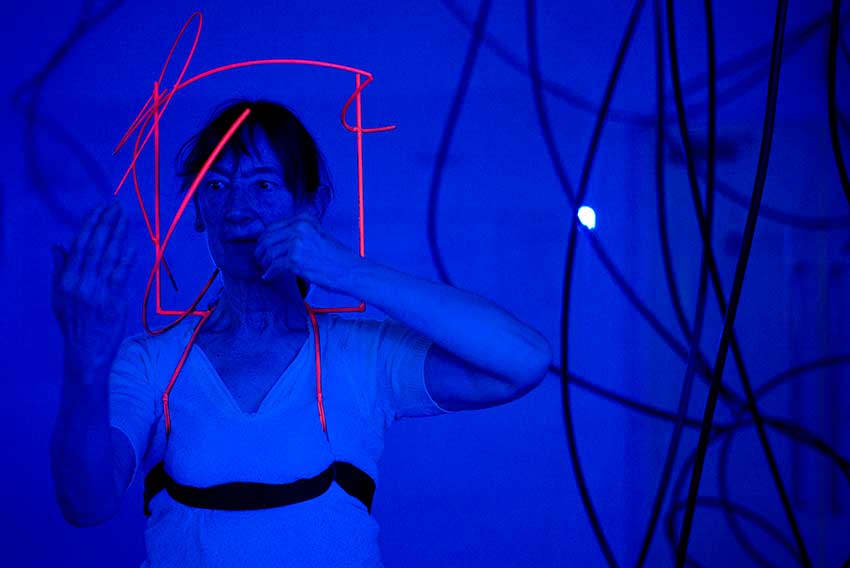

Teow Yue Han: Hi Rosana, I’m thrilled to be introduced to your amazing body of work through so-far and CLOT. Much of your work focuses on visualising gestures in the form of sculptural “scribbles”, complete with headgear, video and sound, performances, etc. How do you decide on these translations of gestures as material?

Rosana Antolí: I love how you call it, “gestures as material” because gestures are something so ephemeral and “material” is a word that has so much weight. I love the contrast between those things.

To your question, it really depends on the project, the movement or the action that I’m going to work with. I might need gestures or actions to be more insistent. So I record and I reproduce them in a loop or on video, or I digitise them. Or maybe I need to find something more poetic, textural, and instead use a sculpture.

Teow: What about the headgear that you created for DERIVILLE? Where do those strokes come from?

Antolí: I translated drawings based on the movements of the performers into metallic sculptures, so the bodies of the performers became sculptural bodies too.

Teow: In a way, they are like fingerprints or imprints of their gestures.

Antolí: Yes. When you try to archive or to translate a gesture, it’s almost like doing something utopian, because it’s about trying to capture the impermanent, the ephemeral and about making that tangible. That drawing or extraction is a very beautiful process because it’s dependent and rests on the shoulders of the performers. You are also an archeologist of gestures who looks to archive movements. You’ve orchestrated some over distance, while I map them in a one-to-one relation. But our outcomes are very similar, because we have uploaded them into the virtual realm, and created dialogues between them.

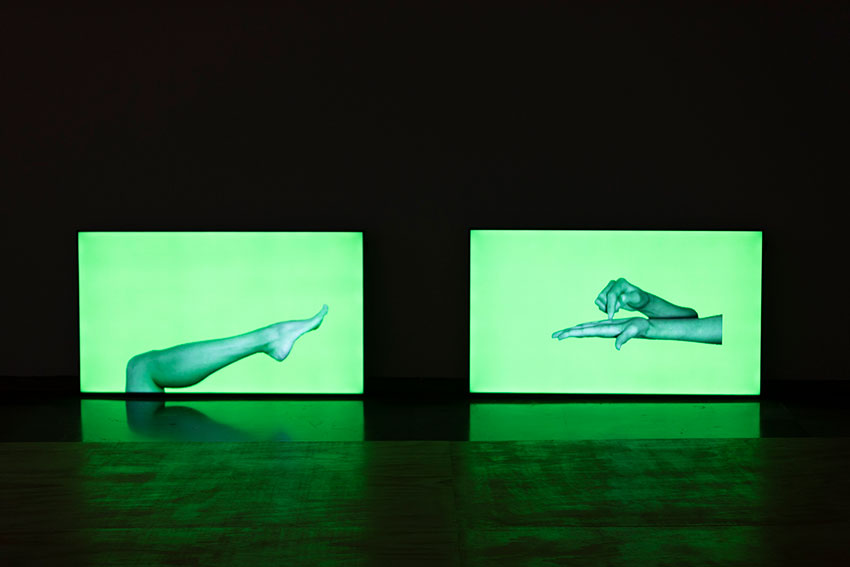

Teow: For me, I don’t really see it as creating an archive, though we should be very conscious of the way our movements are captured on a daily level. I use filming, live-stream videos and mobile devices as both opportunities and obstructions to movement. I try to explore what happens when a performer is performing while also becoming a cinematographer of sorts, filming with those mobile devices. The performer functions in both roles simultaneously.

Antolí: What charge do gestures have for you?

Teow: There is this idea of the gesture entering into the broader network — a network of gestures. That’s closer to the idea of the “dispositif”: how physical gestures ripple into the digital world resulting in a kind of digital movement. These digital signals or the data streams can be quite different from the physical movements that we see in real space and time, but I’m interested in how these two spheres interact.

Antolí: When you say you’re recording these gestures and playing them in different devices, do you take them directly from the performers, the audience, or do you reenact them? In that sense, what sort of filters do the gestures go through?

Teow: The performers have interactions with the phone, but they also feed off the audience.

Antolí: Does it occur in an intuitive way for them, improvising how they feel with the device?

Teow: It’s definitely more improvisational in terms of how both the audience and the dancers respond to that interface. There are some set movements, but there are also segments that allow the audience to come into the picture and to interact. In my more recent work, the device has disappeared. What I’m trying to do is to focus on the quality of the interaction between the performers and the audience, based on a system that guides the process.

The performers have certain rules, a logic that could be derived from a kind of algorithm, or a certain machine learning process that they internalise and then act out those gestures. So it’s not so much about interacting with a device now, but it becomes more of a facilitation of interaction between the dancers and also the audience. Going back to what you termed the charge of the gesture, for me, it’s about examining gestures that have been instrumentalised by the state through smart technologies, and seeing how they can be subverted. For example, in the work How Long is Now (2006) by the artist collective Public Movement, the performers used a popular Israeli dance to block a crossroad in the street. I see that piece as a potential for movement — that we can use common gestures that are out there in the world to create some sort of resistance.

Antolí: Exactly. I wrote my MA thesis about gestures of resistance5. Everyday gestures can become micro-political reactions to what is happening.

Teow: I guess we both have an affinity for “social choreography” as a form of resistance. My own master’s thesis was titled “Performing the Smart Nation: Towards a New Social Kinaesthetic”. What are some of the potentials or limitations of social choreography in your work?

Antolí: Social choreography implies both an unlimited and a limited potential. As artists, we are just giving guidance, and at the same time, we are also a part of the same audience that is co-creating and performing the piece. This poetics — what we want to say with it, how we want to contextualise it — is our due as artists. The limitations come when you work with live bodies, with an audience in a gallery or museum that has not been trained beforehand. They are free to enter the exhibition or public space, and there is a certain grade of uncertainty because you don’t know what is going to be the outcome. And yet that unknown is beautiful! We are always continuously performing, always in a state of flux, in a mutable performance where the options and the potential of this social choreography are unlimited. You and I have much in common: choreography, dance, gestures, fluidity. All of these things have a lot of musicality to me, like a score where you have to organise rhythms and silences. The performative is always the uncertain “patron” in the equation. How do you choose the performers in your work?

Teow: Every performance has its own conditions that allow it all to happen. Usually, I look for performers with an interest in the themes of my research. I also want to uncover their personal embodied knowledge, for example, maybe they know traditional Malay dance, or they play football. Then I work with them to expand their vocabulary of embodied movement. We start off as friends, collaborating, and that builds and adds into the work.

Sometimes my work arises out of a collaboration with a dance company, such as with my most recent piece Alice, Bob and Eve. For that, I worked with three of the company’s dancers, with their race, gender, and the way that they individually performed. In this case, the work was definitely more choreographed, though we allowed some free play for the audience to enter in. It became this entire system that constantly changed and shifted, according to how the audience responded. We also had an external facilitator, a Siri-sounding voice that was orchestrating the whole flow of events.

With Alice, Bob and Eve and previous pieces, I want to show how technology has penetrated and homogenised our movement. When someone holds an iPad and walks around, they more or less look the same. Or when I’m swiping my smartphone, this digital movement goes somewhere else and rebounds back on a kind of planetary scale.

Antolí: But to me, gestures are not completely universal. For example, some years ago in London, when you’d go to see a performance, there was a trend where all the performers were very skinny, white dancers in their 20s and 30s. So it would be very different to have these individuals perform a gesture, compared to having a woman in her 70s perform the same gesture, because the body is completely different. A gesture has a different texture and meaning according to who performs it.

Teow: I agree. There was an exercise I conducted with my performers to interpret those somewhat homogeneous smartphone gestures according to the pre-existing embodied knowledge each one had. Everyone swipes slightly differently, and that’s constructed by individual embodied knowledge.

Antolí: I think that individuality leads to a richer empathy of experience along with the manifold outcomes.

Teow: Yes. On another level, perhaps the more nuanced approach to these “universal” digital gestures would be a socio-political contextualisation within a specific city or space.

so-far: Yue Han’s work often responds to the particular urban conditions of the Smart Nation policy the government has implemented in Singapore. Rosana, can you speak about how your work responds to specific cities or localities?

Antolí: Yes, I have done work that responds to the context of cities, like in Argentina, Colombia, or in London, or with all the cities in the travelling work Virtual Choreographies. I ask the concrete question, “What is the moment that we are living in right now?” Some of those replies are more direct, or some are more open. For example, my work Chaos Dancing Cosmos is site-specific, where the movement and sculpture respond to the architecture of the place where it is installed. The piece Endless Dance was created in a moment of political transition here in the UK, where we thought that we were going to move to one side, but we were actually coming back to the other. This pendular movement in politics gave me the impetus to place a huge pendulum in the installation. So whether it’s very subtle or pointed, I always respond to the social or political situation that I’m experiencing at that moment.

Teow: One of those works you mentioned that I’m most fascinated by is Virtual Choreographies. I saw that you’ve been working in different locales, and it’s an ongoing “archive” that also has a life online. Can you share a bit about the trajectory of this archive over the years and how has it grown?

Antolí: Virtual Choreographies was supported by the British Art Council and arebyte gallery. This project started in London and has been moving through different cities. I always choose an area of the city that has some social movement. This means that the area cannot be homogeneous; there has to be different kinds of people living there because of gentrification or new construction. People are moving, arriving or leaving — there’s a clash of cultures that I try to map.

Teow: What did you discover about the relationship between the body and the camera?

Antolí: At the beginning, I filmed with my professional camera, but people would get very self-conscious. So I needed to record in a way that was less aggressive and began to use my mobile phone. People are more comfortable with the mobile device, so they would get more relaxed and participative when I would ask them, “What is your movement? Would you like to give me one minute of your time?” So the change of the device helped a lot to engage people more with the project. Later, when I had compiled this archive of gestures in a photo studio with a proper camera, I de-contextualised them. I took only the movement and the gestures to conduct a digital, virtual choreography of the area that would be later uploaded online accompanied by music from a local musician. Depending on the area, the gestures said a lot about the culture of the people that were living there. The gestures in a neighbourhood called Cuatro Caminos in Madrid were totally different from the gestures in Hackney, London.

I want to continue this project perhaps for the rest of my life, and see how it will change. I’m sure that the gestures that we are doing now in 2020 are going to be totally obsolete in twenty years. For me, it’s intriguing how our gestures are going to evolve, and how the areas and cities that we are working and living in are going to change. So these performances are not only restricted to a physical or temporal place. They are expanded in space and time. With regards to expansion and continuation, you also have spoken about “fluidity” in your work. Right now, I’m working with tidalectics, or how to visualise a fictional oceanic future where everything is connected, unlimited and in constant movement. I am curious to see what is your approach to this fluidity outside Zygmunt Bauman’s theories6?

Teow: My entry point is actually through fluid dynamics in the 19th Century by an engineer, James Thompson. This is how the term “the interface” was first coined, and it is a sort of boundary that controls the reciprocal relationship between two bodies of water. The interface is a key node to my understanding of dance as a constant flux, relationality or fluctuation that is in search of an equilibrium.

There is some synergy between the idea of the interface and your concept of tidalectics. There’s a certain kind of fluidity in digital infrastructure as well, in the form of flows and streams of data that are constantly being tapped. In Singapore, we have a platform called Virtual Singapore7 where live flows of data are spread out over a huge map of the city that almost looks like Google Earth. Our government uses this platform to test possibilities for city planning. They have Internet of Things (IoT) devices around the city that can measure humidity, noise levels, pressure, temperature, and so on. The visuals they use are quite similar to your sculptural work, with a lot of lines flowing around the city.

Along that train of thought, with tidalectics, perhaps it’s about finding a way to remove choke-points — to move beyond these governmental infrastructures, and I guess that’s what you’re trying to propose. Is this form of future tidalectics linked to the immortal jellyfish and the idea of the infinite loop?

Antolí: Yes, the immortal jellyfish has become the banner for this recent project of mine. This species of jellyfish have been found to be immortal and they keep on repeating the same movements in an infinite loop8. I found that it was an opportunity to talk about a post-humanist situation where limited or defined bodies are no longer a reality. The jellyfish is composed of water inside water, so you doubt what kind of shape it has, or it doesn’t even matter because it’s totally dispersed within the atmosphere. So the characteristics of the immortal jellyfish led me to fictionalise this future, imagining what would happen if everything was connected. There would be no reference point between the floor and the ceiling as if everything is floating, fragmented, and we wouldn’t have limited bodies.

CLOT Magazine: If you could imagine a collaborative work together, how would you envisage it to be?

Antolí: It would be very appealing to think about a choreography that could be done in Singapore and London at the same time, without limitations and making use of this fluidity. We don’t have to do it for a stage or for a space, but people can know that these movements that are happening in London are also happening in Singapore. I’d be very keen to do it!

Teow: When I was studying in London, I was exploring the telematic body and using live-streaming to beam performances from London to Singapore. There’s definitely such a rich space between two cities to do something like that.

1 TikTok US downloads went up 27% in the first 3 weeks of March as compared to February, according to Music Business Worldwide

2 By now, everyone is aware of Zoom’s compromised cybersecurity. Read more

3 Two of Singapore’s government agencies, the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) and the National Parks Board (NParks), have released websites to monitor crowd density

4 Gia Kourlas, “How We Use Out Bodies to Navigate a Pandemic,” New York Times, March 31 2020

5 The full title of Rosana Antoli’s thesis is “Social Choreography: Everyday Gestures as an Act of Political Resistance (and Absurdity in Performance Art)”

6 Zygmunt Bauman was a sociologist and philosopher who theorised the idea of “liquid modernity” as a description of the state of constant change and flux in postmodern society

7 Read more and experience this platform by Singapore’s National Research Foundation here

8 The Turritopsis dohrnii, or the immortal jellyfish, have developed the ability to return to a polyp state and reverse the biotic cycle, allowing them to bypass death.

(Images courtesy of the artists)

This is the first in a collaborative interview series between contemporary artists on the so-far platform and those within CLOT Magazine’s network. The format attempts to seek out alignments between new media practices across the globe, and forge serendipitous networks through dialogue and open sharing sessions. This series is supported by the Embassy of Spain in London.