Interview by Ania Mokrzycka

Approaching storytelling as a technology and a site of knowledge and fiction as a form of power, the French-Colombian filmmaker and visual artist Laura Huertas Millán creates embodied, affective experiences in which aesthetics and politics intertwine. Provoking sensuous, emotional responses, her work confronts the audiences with complex and, at times, challenging subject matter. Interested in strategies of survival, resistance and resilience, Laura Huertas Millán acknowledges and examines violence and inequalities permeating contemporary socio-political structures. Following the need to contextualise and navigate her own situatedness in France as the ‘other’ and an exoticised subject/object, she delved deeper into research and archives, searching for ways to represent diasporic communities, their histories, oral traditions and lived experiences.

As part of an investigation into deconstructing colonial narratives, Laura Huertas Millán turned to their manifestation/technology of dissemination – ethnography. Considering it simultaneously, a form of fiction-making or storytelling opened up a possibility of reclaiming and decolonising the discipline and its modes of representation. Huertas Millán’s project Ethnographic Fictions, which includes films Sol Negro (2016), La Libertad (2017), and jeny303 (2018), critically engages with the contradictions and complexities inherent to ethnography, allowing the artist’s own fictions, imaginings and sensibilities to come forward and propose new understandings of past, present and future.

Her propositions are built from a deep-seated sense of affinity and kinship. The artist’s relationship with her characters is intimate, but never extractive. Making space for her participants and protagonists’ voices, the unfolding stories slip in and out of truths and fictions, the observed and the enacted, the individual and the collective, defying categorisation. Sol Negro portrays a fictitious opera singer based on the artist’s aunt, who also embodies her in the film. The Labyrinth explores memories of a former drug worker and the real and imaginary spaces he passes through. Fiction both reveals what would remain inaccessible, repressed and unspoken and protects people involved in Laura’s work.

Since 2018, Laura has been working on the notion of pharmakon (from greek phármakon – remedy and poison). The Labyrinth (2018), Jíibie (2019) and her upcoming feature film are all part of this research bringing together psychotropics, storytelling, neocolonialism, narcocapitalism and geopolitics. In Jíibie, the rituals and practices surrounding the use of coca plant powder create conditions for collective thinking, working, learning and organising to take place. But, as Millan herself sets forth, processes of healing and living together are often complex, troubled and disorderly.

The exchange of experiences, knowledge and stories that underpins her work is also expressed in her mentoring practice. As part of the Forecast platform initiative, Laura defines her role outside the limiting master-student dichotomy, attempting to sustain more horizontal and bilateral approaches. She is interested in working with artists who pursue stories that connect us to nature in its undomesticated states, that allow us to feel and to think as more-than-human beings, that excavate and unearth repressed ways of communicating with the natural world. Across all the tangled offshoots of her practice, Laura Huertas Millan nurtures a sense of community. She conjures her human and non-human subjects, collaborators, mentees and audiences, to collectively imagine spaces of attunement, symbiosis and altered perception.

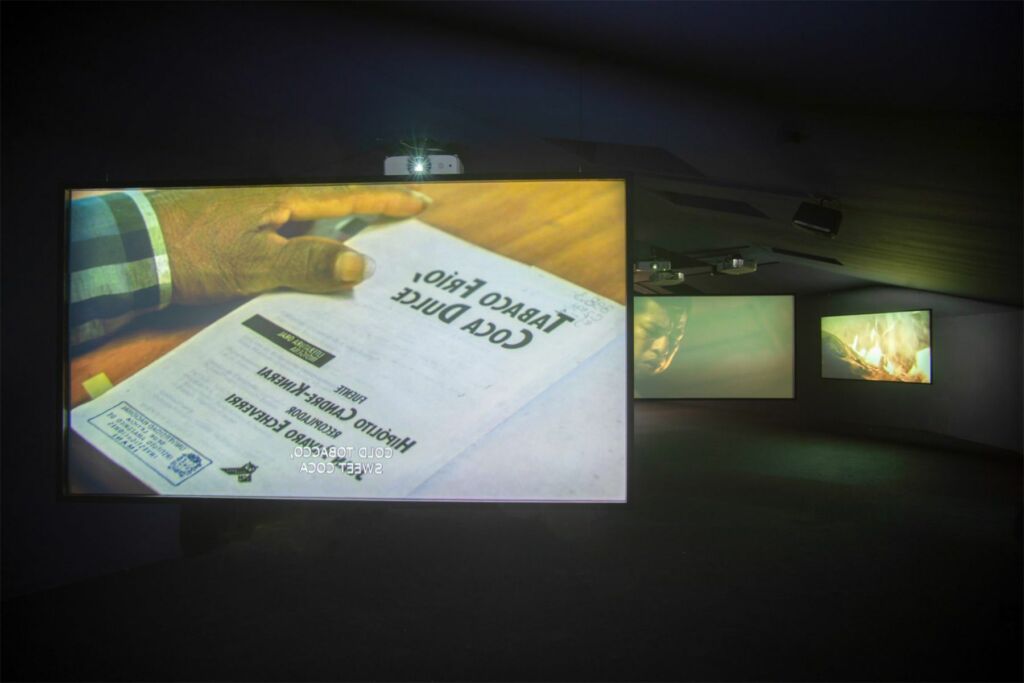

Right: The Labyrinth, Laura Huertas Millán. Installation view from Esa Historia no es la Historia, Espacio Odeon, Bogota, Colombia (2020)

Your practice sits at the intersection of cinema, contemporary art and research. How do they feed into and inform each other, allowing for complexity and fluidity in your work? Does this interdisciplinarity open up new possibilities in the context of fictioning?

The art I’m interested in proposes multi-layered experiences where one’s senses and thinking are activated. I don’t really make the difference between all these genres. I don’t necessarily follow the distinction between the intellect and the body, as if they were disconnected. The art expression that interests me draws from embodied experiences, history, memory, collective living together, nature, and apparatuses of imagination and vision. At some point, that can be called interdisciplinary, but I never really made the separation between all these registers; in my case, they built together creatively, thus pretty organically, through my sensibility (things that I like, that I’m concerned about, how my body reacts to a situation or environment).

I also started research projects when feeling a need for more representation of diasporic histories like mine in the political and cultural field in France. I needed a community of active and past artists to communicate with, to learn from, so I started taking research more seriously. That curiosity had considerable consequences in my work; inevitably, I started to position my practice on the ones I’d been investigating. I also realised throughout the time that I had a platform to give visibility to artists who inspire me and don’t necessarily have the same reach.

The visual language of your films is quite striking and feels very instinctive; while engaging with charged subject matter, you also embrace the affective potential of cinema and draw the viewer deeper into the stories you tell. How important is it for you to make these experiences accessible on an embodied, emotional level?

I grew up in a Colombian context where storytelling and oral narratives were part of our daily life experiences. For example, when I was a kid, we had an intense drought that threatened the production of electricity, which caused energy rationing. So for a couple of years, my family spent most of our nights in the dark with candlelight, singing together, telling each other stories, and playing games. The 90s in Colombia were highly violent times, so we found solace in imagining narratives and teaching each other songs or jokes to remember. So I found in the cinema a site where to build this sense of home and place, where the imagination is activated, where I feel inside my body again, as well as the possibility of being together with other people.

Do you find that through this viscerality, your films somehow bear a closer connection with the oral storytelling traditions?

Absolutely. Coming from a (neo)colonised context where the history we were taught at school was mostly told from the coloniser’s perspective, I’ve always been drawn to popular and counterculture, where I found more accurate representations connected to my own life. And oral traditions are connected to communities who were racialised and excluded under the pseudo argument that they didn’t have technologies or knowledge (while being constantly expropriated and exploited). So I take oral tradition very seriously, as a storytelling device, technology, and site of knowledge and memory; oral storytelling traditions are a central component of our political history.

There is a sense of intimacy present in your work that often confuses distinctions between observation and enactment. For example, in Sol Negro you worked with your aunt, building a character based on her life. How did you cast and build relationships with other protagonists in your films?

I like to build long-term relationships with the people I work with, although that is only sometimes possible. In any case, the stories that I want to put forward come from connections with persons or places. Each project has its own process and history, and I honour that process and that encounter.

In Sol Negro that was even more radical because of the affects inherent to family bonds. The film became a work about literal kinship. But in each one of my films, there is always a form of the inner search for belonging, which might enhance the sensation of intimacy for a viewer. I don’t think in terms of binary between observation and enactment; most of my films are about presence and engaging with someone. And that sometimes implies building scenes together or imagining situations to tell a specific story. That also has led to moving gradually towards forms of co-authorship and collaboration.

Vulnerability and strength, beauty and violence, truth and fiction coexist in your films and collapse into each other. Defying binaries and allowing a plurality of voices and narratives to emerge is central to your work. How do you achieve this syncretic vision?

I don’t think my vision is more syncretic than any other. All artistic works aim to achieve complexity and get inspiration from many different sources. However, I’m also inspired by reality, and that opens space for many elements and contradictions to coexist.

The “ethnographic fiction” project, developed for your PhD in ethnography and cinema, can be defined as a gesture of undoing the colonial narratives of domination. Can you tell us more about how the idea for it came about, your methodology and how it resists historical forms of ethnography?

It was a long process that started out of the necessity to understand better my situation in France, feeling othered, isolated and exoticised. When I learnt about the colonial exhibitions, the so-called ethnological exhibitions (human zoos), and the history of taxonomy and botany while witnessing the denial in France of the colonial past and the contemporary racialised violence, I felt even more enraged. So I started a series of works to expose and deconstruct the colonial narratives still affecting the present day and concluded that ethnography has such strong ties to colonialism that it had to be considered as storytelling, and in most of the early ethnographies, as fiction-making. And then this anti-ethnographic and anti-colonial impulse echoed works of filmmakers I admire, such as Trinh T. Minh-ha, and practices coming from Global South ethnographies that integrate fiction in their methodologies to decolonise the discipline (Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, to name one). So I engaged in the practice-based PhD to think about this contradiction through my films.

This critical anti-ethnography was linked to Jean Rouch, who coined the term ‘ethnofictions’ as something positive (a “shared anthropology”, as he said). His work has been a model and anti-model at the same time; I started working with and against his ideas. That’s why I don’t reclaim his legacy but critically respond to it. Perhaps my ethnographic fictions are acts of appropriation and detournement (which are gestures that I employ quite a lot in my work in general) when it comes to anthropology, and that’s why I don’t use the term “ethnofictions”.

My methodology has always been flexible, studying these different practices, letting my refusal and sensibility speak through the work and making an ally of fiction to tell other narratives gradually.

I am very drawn to the concept of a pharmakon, a cure and poison at once. You have approached it thinking about the coca plant, its ancient origins, uses and the role it plays in contemporary society; The Labyrinth (2018), Jíibie (2019), and an upcoming feature film are part of this research. You align pharmakon with fiction – how do you unpack this relationship?

A pharmakon is an entity that is both a poison and a remedy. Fiction is constantly politically weaponised to impose or prolong violence and inequality. It’s the core of propaganda and ideology. I’d like to approach fiction differently, as a form of power but also as a site engaging some responsibilities. To me, fiction is a psychotropic. As psychotropics, it is something of a larger scale than just one individual; it has the ability to influence, a large number of people; it can also cause destruction and death. So it means working on how it is dosed, and what kind of influence one wants to have through storytelling.

And I don’t take the word psychotropic here lightly. My interest in the idea of pharmakon has to do with my own experience of mental illness and being part of a society highly traumatised by centuries of civil war. So, fiction, or better storytelling, has also become for me a laboratory to imagine forms of contributing to a collective discussion around healing and living together. Still, that process is far from being a sanitised and undangerous activity. On the contrary, there is an amount of risk-taking and forward-thinking necessary to be able to imagine political and social change.

As a mentor, you want to work with practitioners “who see fiction and storytelling as a space of emancipation, freedom, and collective ecological care and (…) who have to resist systemic and colonial violence through their practices.” What is your process of supporting them in finding and/or amplifying their voices and navigating through the systemic structures that silence them?

For Forecast, I have been mentoring Luciana Decker Orozco. I’m not sure the word mentor applies to our relationship because the word itself comes from a patriarchal tradition of the “master” and the “student”. This hierarchical relationship is not exactly what’s been unfolding over the past year among us. With Luciana, the relationship has grown more as being the older kin of someone, being from an older generation, having encountered similar questions beforehand, and both belonging to the same family of work. I hope that Luciana feels confident to count on me as someone who she could turn to with questions around the sustainability of her practice, audience building, and ethics of the work, not because I know better, but just because I usually have to deal with similar issues. Together, we can find productive answers.

Being a mentor has a lot to do with what I do as an educator, although being someone’s mentor implies sharing networks or recommending someone for collaborations in the professional field, something that I wouldn’t necessarily do in another context.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

Burn-out.

You couldn’t live without…

Resilience.