Interview by Daniela Silva

Michail Rybakov is a media artist and researcher whose work spans from product choreography and experimental film to computational art. His main interests include physical engagement and human experience in the post-digital world. He’s curious about how the everyday world choreographs us, how we can design this choreography, and why.

More and more, the interaction with the world around us happens through our fingertips. Touch user interface (TUI) can be extended to everything designed into an information device with which a person may interact — in essence, a user interacts with an application or a website. The touch interface is more than just an organic way to click on something. We see gestures unfold, and this kind of limited interaction inhibits the use of our bodies to the full extent. Our bodily expression in everyday life is restricted. And all because of how the things around us are choreographing our movements.

Based on this interpretation, Rybakov developed his project Peekaboo – a mirror that only reflects when the user screams at it. The goal of Peekaboo is to make us question how limited our bodily expression is in our daily lives. However, the object does not make itself easy to use as it is stubborn: it forces us to use the full range of our voice, and when we stop, it stops as well.

Peekaboo acts as a mirror in more than one way. As the loud voice vibrates through your body, our perception of our own body sharpens – the scream acts as a trigger, a wake-up call that places us in the current space, in the present moment. Following his research on embodied interaction and human experience in the post-digital world, Rybakov presented some of his experiments and work under the title Shameless plants during the festival OTHERWISE 2022.

Could you talk a bit about your interests and inspirations for those who might not be familiar with your work?

My works are primarily about bodies in a post-digital world. We’ve got some of our senses greatly extended by technology, while others, like proprioception, touch and smell, just wither away. They are, however, hugely influential in how we relate to the world and spaces other beings around us, so I want to reactivate them.

I like to design small choreographies, or better yet, small situations that create a choreography through exploration by the visitor. For example, in the exhibition “Critical Zones” at ZKM Karlsruhe, I created a soft ground for visitors to walk on, every step feeling a bit different from the one before. The very video-heavy and didactic exhibition created a space of purely touch-based exploration. Our feet are, after all, very sensitive organs of touch. Still, ever since we invented the wheel, we have designed our places of living to be most friendly to wheels and not try to maximise the pleasurable experiences that our feet can have.

You first debuted as a media artist with the project “Peekaboo”, where you challenge the limited body interaction experienced in everyday life. What was the creative process behind it?

Peekaboo is a mirror that does not reflect until you scream at it. I felt that we lose something when we simplify away the everyday bodily interaction. A few generations before, when you wanted to cook something, you had to gather wood, split it into firewood, start a fire, bring water from the well, and cook the food. In rich countries, all this process has been designed and engineered away, and now you have stoves with a touch interface or smart ovens that you control from your phone. So the whole experience of food becomes disembodied, limited to light touch, at least on the production site. Only embodied consumption is left.

I wanted to bring rich bodily interaction back into everyday experiences and chose the act of being loud as the performative trigger. After all, living in close quarters, in cities, we hardly ever experience the full range of our voices resonating through us. We have to visit football games and concerts for such a basic task – unique places for being loud. The mirror part came later and worked surprisingly well, as the screaming person finally sees themselves. Seeing yourself screaming is quite an experience, and most people have to stop and laugh at the unfamiliar image of themselves screaming.

You describe AI – artificial intelligence – as where overthinking meets stupidity. Can you elaborate further?

A lot of what gets branded as AI now could be better described as pattern recognition or pattern generation. And while that is a great and exciting thing (humans have been much better than machines at pattern recognition until now), it has little to do with intelligence. There’s also this notion that if we just throw massive computational power toward a problem, we will find a solution if we just think hard enough and long enough. But that doesn’t work with pattern recognition that way. We could train it on massive datasets, but it still will be limited by the human-created dataset that will inherit all of our biases and the limited ways of viewing the world. So no matter how powerful the ‘AI’ is at answering questions, it will only be able to see the patterns we taught it to see.

Your line of work has recently become very much focused on AI technology. What is the purpose of your research in that field? What do you wish to accomplish?

AI is interesting because it is a disembodied technology making a judgement on an embodied world. Like a ghost that’s never been alive. It struggles to grasp what’s going on; it’s in a constant state of sensory deprivation and can only ‘remember’ what we train it to remember. It is endearing in its clumsiness, especially towards topics that are perceptual and hard to describe. What is a body? How do humans map and navigate space? If I ate a salad for breakfast, what part of me became salad now? In the failings, the cracks of a new technology, we could see a reflection of the human condition.

You were one of the participating artists at the OTHERWISE festival 2022. Can you talk about the work Shameless plants that you presented there?

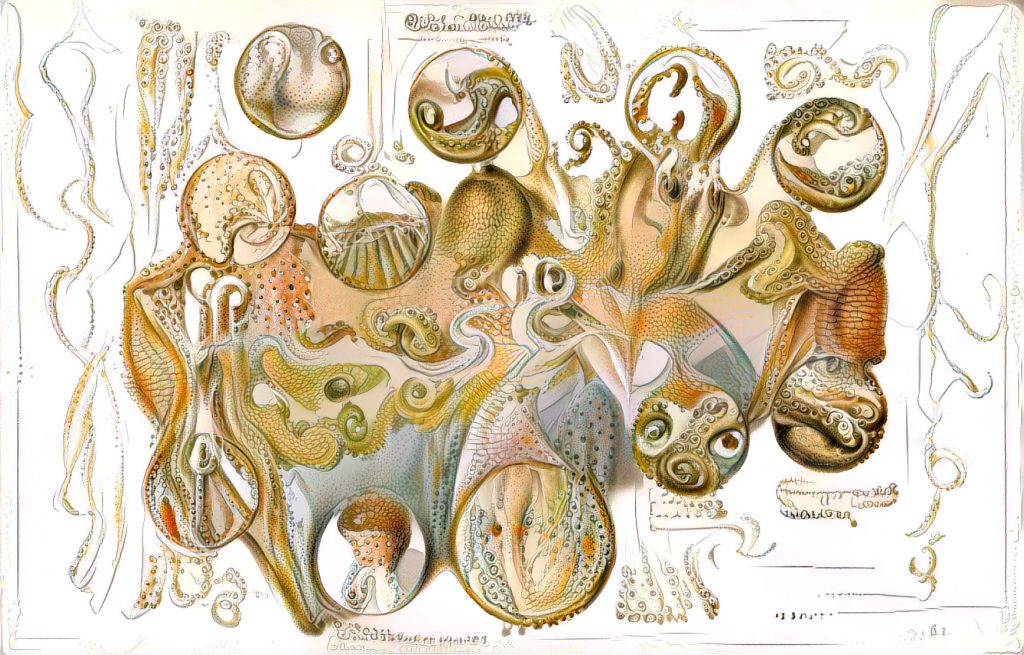

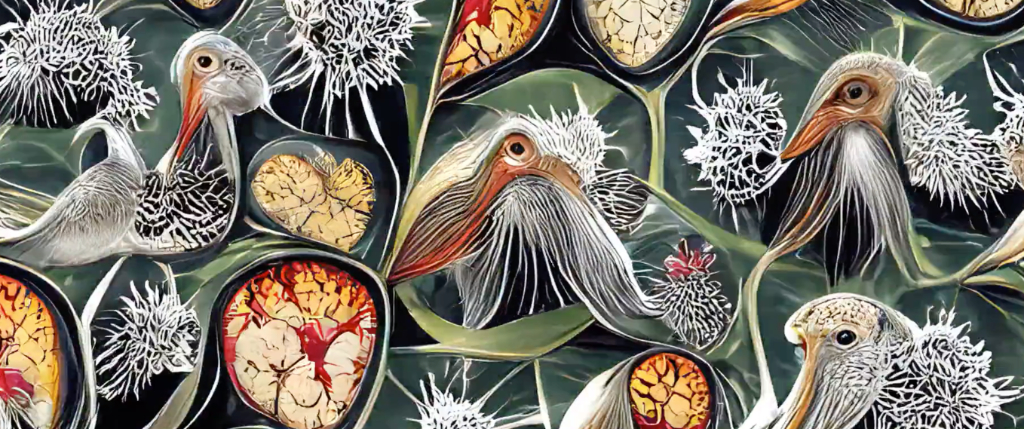

I always found it fascinating how we tend to anthropomorphise plants while denying them all agency since they can’t move or communicate in a way that is easily understandable for us. So, I asked myself, what would happen if we treated plant bodies the same way we treat human bodies? What if they could feel shame? Could feel the gaze of others?

In one project, I am exploring the life of a mimosa that is cybernetically extended by an AI, a motor and a curtain. The AI is trained to recognise human bodies, and once it sees one, the motor closes the curtain hiding the mimosa. In a way, the viewer has to give up the conventional way of being in a human body – they can try to change pose, hide behind plants and so on – to see the plant body. Seen from another perspective, the project is also about anthropomorphising the mimosa so much that it inherits the very human sensitivity towards being seen, not just being touched. If you want to be human, dear plant, you have to inherit our neuroses too.

The other project too treats plant bodies like human bodies. This time by imagining the situation of a plant being naked as something shameful. I made a series of very amateur-style erotic photographs in which potted plants take the courage to finally remove their pot and show their roots to the camera. Uncensored.

What are you working on now?

The projects shown at OTHERWISE are very much work in progress, and I will continue working on them. I’m also very interested in the phenomenon of light (as it fills the space) as something that people share when they are in the same room. The ability to share space and to share light diminished during the pandemic, and I’m looking for ways to bring it back.

What’s your chief enemy of creativity?

The pressure to perform. I like being liked and appreciated. But once I start being guided in my work by the desire to be liked by or impress some audience, nothing good is produced. So, instead I work the way I did as a kid – gathering beautiful stones by the river and tree resin in the woods (I imagined them tiny smelly planets) and sharing my fascination with them with everyone around me.

You couldn’t live without…

I really like Crème Brûlée.