Interview Agata Kik

After having started his career as a music journalist, Todd Eckert produced the feature film ‘Control’ about Joy Division’s Ian Curtis. Directed the North American sector of UK’s game developer Eutechnyx; and the content development at Magic Leap, where he finally got introduced to Mixed Reality, whose immaterial grounds he now conquers together with his Tin Drum team.

Founded in 2016 by Eckert, Tin Drum is a UK- and US-based media production collective consisting of designers, coders, artists, and scientists who explore the themes of presence, permanence, embodiment and, more broadly, the ways that contemporary technology influences being together nowadays. All this is done through works that focus on location-specific groups and which combine the two techniques of volumetric capture and Mixed Reality.

With a silent quest on his mind to ever-enhance the ways of telling stories, of immersing ourselves into the world, Eckert, thus, never stops questioning. He does not assume; does not extrapolate, but with his ground-breaking approach to technology, he aims to create communal experiences that screen-based devices, so far, have ended up constraining.

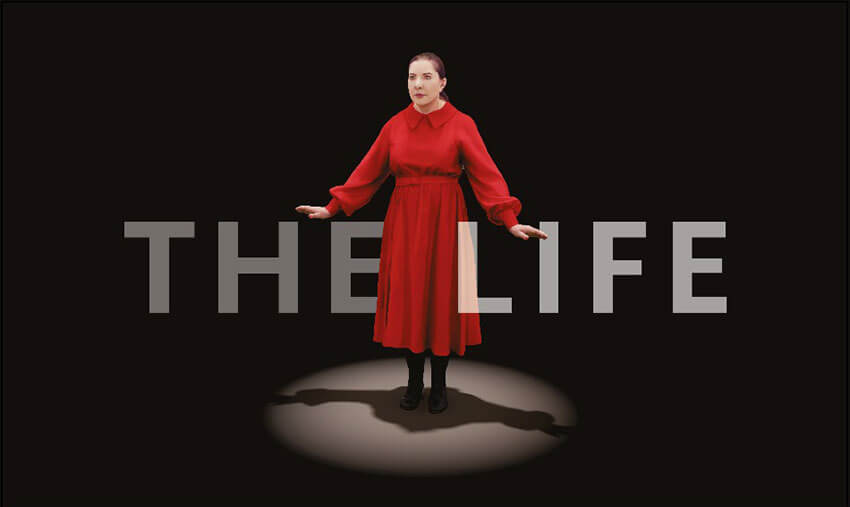

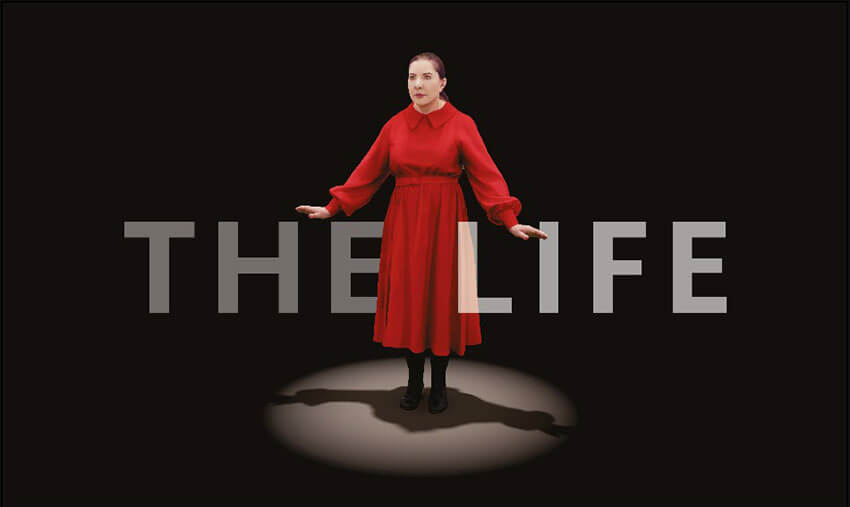

Unlike smartphones, for example, Mixed Reality technology consisting of wearable glasses does not repurpose the content, and so the work has to be designed in a special way to employ the whole potential of the devices. In February 2019, directed by Eckert, Tin Drum debuted with their first art exhibition, ‘The Life’ by acclaimed performance artist Marina Abramović. Happening repeatedly over six days at the Serpentine Gallery in London.

This 19-minute-long piece was the world’s first performance project in Mixed Reality, the first ever such a large-scale wearable augmented reality experience, facilitated via Magic Leap One, the lightweight wearable spatial computing goggles introduced earlier this year. While the artist came up with the concept herself, Todd Eckert directed the performance, having achieved what he had aimed for, making the work feel as close as possible to an experience of a live act, though without the artist having ever physically to appear in the gallery.

The Tin Drum’s work with Mixed Reality technology stems from the aim to produce deeper and more intimate relationships between artists and audiences, and also more genuine relationships in the contemporary art spaces. In The Life, for example, the artist was performing through the lenses of 50 augmented reality headsets simultaneously. However, what has distinguished this work from Abramović’s earlier experiments with technology was the fact that, unlike Virtual Reality, Mixed Reality does not erase the viewer from the image, making the virtual content as real as belonging to the material world.

To be able to incorporate audience agency into a recorded medium is a revolutionary invention for artists working with technology to benefit from and also for their audiences to experience such a situation that until recently could only belong to their imagination.

Todd Eckert, with his collective Tin Drum, thus, opens these never-imagined-before doors to the experimental artistic invention, preserving presence into infinity, transforming the material into the ephemeral real, giving everyone a chance to understand the world better by augmenting the surrounding reality with any elements that one is capable of dreaming up.

How and when the interest in mixed/altered reality came about?

It was in 2012. I produced a feature film about Ian Curtis, the lead singer of Joy Division, and I met Rony Abovitz, the founder of Magic Leap (a Mixed Reality device manufacturer), through a series of events all related to that film (it’s called Control). I went down to South Florida to meet him, and the technology was in an incredibly early, nascent state. But even then, it was completely clear that the ability to incorporate audience agency into a recorded medium would change everything in a really positive way.

What are your main aims behind Tin Drum, your production studio that develops content for wearable mixed reality devices?

The point of the studio’s creation is the ability to produce deeper, more intimate and hopefully more authentic relationships between artists and audiences.

What has this new media brought to your creative practice?

It’s made me question everything I think I know about telling stories. It’s amazing how much of what we do – really what everyone does – is an extrapolation of what we already know or have done. And that’s fine, but when there are a completely new medium and no template or frame of reference from which to draw, it’s important to question everything. From “Why do we accept screens?” to “What is a point of view” to a million other things. It’s enlivening.

Let’s talk about The life, for which you have been a collaborator throughout. What was the intellectual process behind the inception of the piece, and how did you approach the collaboration?

Marina and I were talking about what the idea of performance means on a really fundamental level – the process of emotional conveyance and presence. We decided we would try to create a piece that would allow the audience to feel as if she was really performing – actually there – forever.

To achieve that goal, we had to focus on the hardest questions of all, which are “What does presence mean in the form of a recorded medium?” and ultimately “Do we feel something when we look in Marina’s eyes?” We were always prepared to abandon the project if we didn’t meet the mark of our collective ambition. Thankfully, we did.

What have been the biggest challenges of this production?

We had to invent every facet of the exhibition, so there’s honestly little that wasn’t hard! Everything from 120 devices swapping out at once to the fact that no one had actually shown using these devices as a real public exhibition – and the most difficult being Marina’s pace of performance. She was purposefully slow and contemplative, which is fantastic.

But such a pace reveals the limitations of volumetric capture in a way that a performance with some speed would not. Ultimately we were able to invent solutions that made it possible to convey with fidelity and accuracy what she wanted. Shaw Walters and Yoyo Munk (both from Tin Drum) were crazy good in what they achieved.

The Life premiered at the Serpentine Gallery, where was exhibited for around a week. Was the reaction of the audience what you had predicted?

The audience’s reaction surprised me a little. I expected people to be amazed by the technology – and they were – but more often than not, they allowed the tech to get out of the way and really got into the meat of the performance.

We went to astonishing lengths to achieve that goal, but I wasn’t sure if it would work. Every day crowds would burst into applause; interesting given that they wouldn’t have if she had really been there but were compelled to despite her not being there. Every day people cried. Every day people mimicked her movements. It was truly emotional on so many levels.

Any upcoming projects you can tell us about?

We’re touring The Life extensively and will make another announcement in the fall. There’s honestly just so much happening.

In times when almost everything is consumed via screens and headphones. How do you deal with screen/digital overload?

I feel like the creation of communal experiences is really important. I feel like isolationist technologies have set society back in ways it doesn’t yet understand, and it’s our goal to alleviate that. Technology to fight technology, I guess.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

I feel it’s a societal thing: the world seems, albeit in varying degrees, to value the maximisation of profit over the transportive potential of stories. Perhaps it’s because profits are measurable, and making stories that really move us is immeasurably hard. I think Mixed Reality is actually the antidote because creativity is a fundamental attribute of anything that has to be created from scratch.

You couldn’t live without…

N/A