Words by Meritxell Rosell

Biotechnology is one of these words that have become fairly ubiquitous in our present days, but is the lay audience aware of what it actually does entail? Dr Jennifer Willet, a renowned and well-established artist and professor in the thriving and growing field of BioArt, brings the “biotechnology lab” a step closer and challenges our preconceptions to raise awareness and ethical concerns.

The idea of the laboratory as a sterile, aseptic, clean, and neat environment can be quite a distorted image, whoever has been in a research lab is well aware that they can be dirty, noisy and smelly places. This is what most shocked Willet when she started her residence at SymbioticA and envisioned the lab as a more organic entity, a kind of zoo (in her own words), where life is orchestrated in a perfectly harmonious ecological symphony.

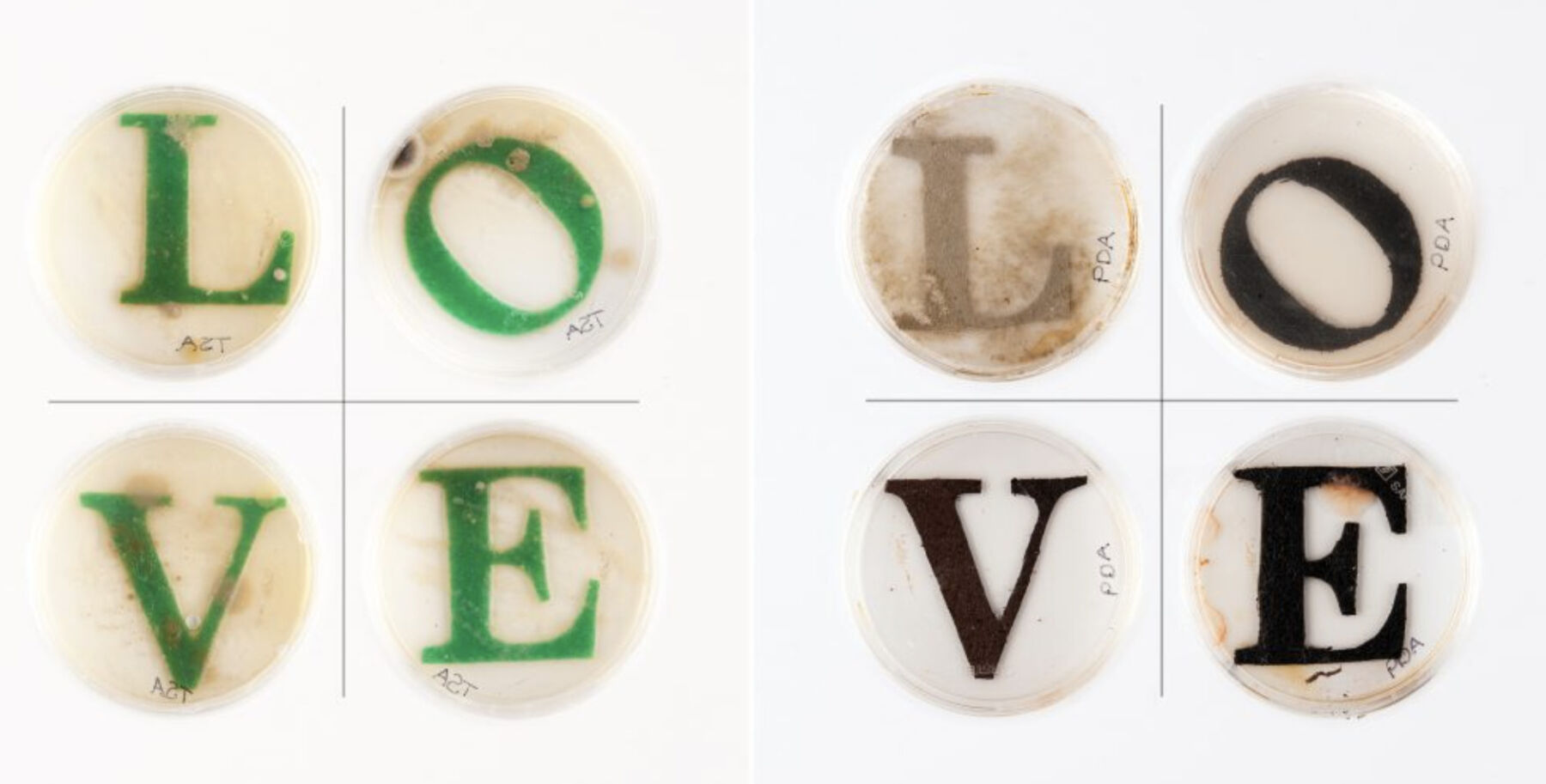

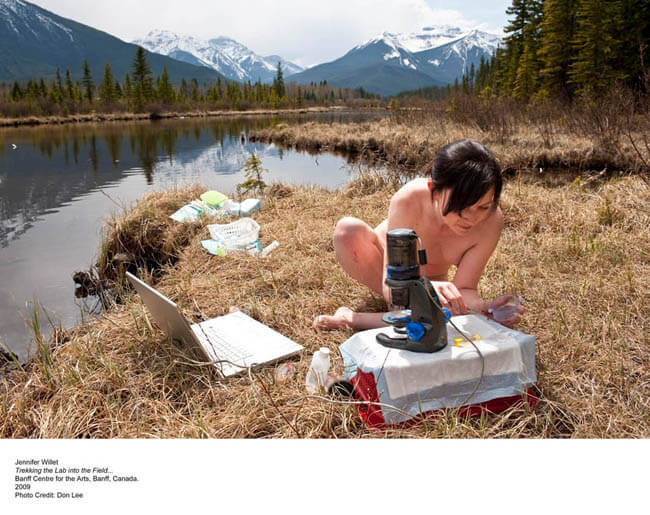

Willet’s work, expanding more than 15 years, has been focused to a large extent on laboratory aesthetics and exploring its representation along with concepts of ecology, dis-(re)embodiment, interspecies relationships and digital technologies with a stress on the biotechnological and socio-political angle.

Her creative universe encompasses the generation of installations, art objects, photographs, performances and critical discourses most of the time all of them in one same project like in Laboratory Ecologies, Cell Break and Trekking the Lab.

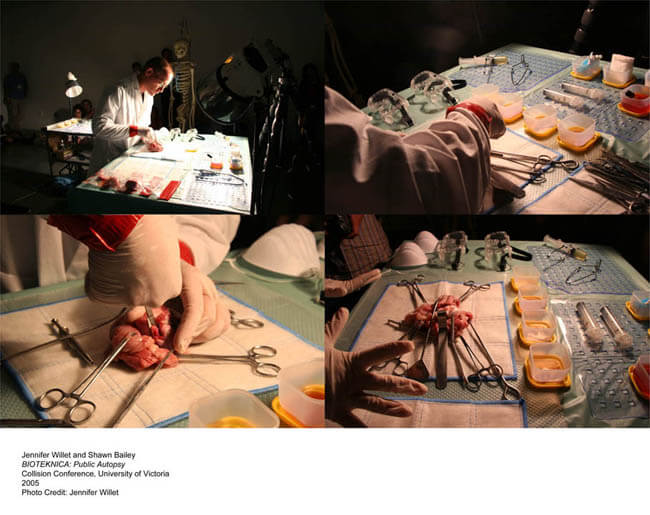

One of Willet’s early projects, BIOTEKNICA, a collaboration with Shawn Bailey, started as a speculative idea of a biotechnology lab only existent in a virtual environment as a means of criticising the contradictions and profound complexities of the biotechnological domains.

With the residency at SymbioticA, the project materialised into reality. Besides, her collaboration with Kira O’Reilly has contributed to a series of photographic and performative documents about the stance of the human body in the technoscientific context.

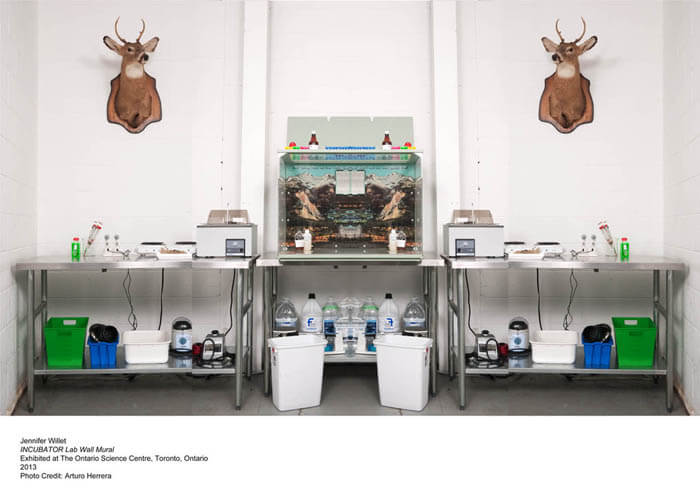

Dr Willet is also the founder and director of the Incubator Lab at the University of Windsor in Canada, where she develops ambitious and fruitful projects like BioARTCAMP, which involved 20 artists, scientists, filmmakers, theorists, and students living together in the Canadian mountains for over a week.

The experiences generated and further work at the Incubator, propose it could be used to re-invent the role of biotechnology in nowadays societies and provide alternative visions for the future; what these would be, we are expectant to discover!

You are a visual artist working in the intersection of art, science and ecology when and how did the fascination with biological systems come about?

In the late 1990’s during my undergraduate degree at the University of Calgary (Canada) I was given the opportunity to draw anatomical studies directly from human cadavers in the School of Medicine. At the same time, my mother was very ill. These two experiences directed my attention towards biomedical bodies as the content for my early work.

However, It was not until 2004, when Oron Catts and Ionat Zurr invited Shawn Bailey and myself (BIOTEKNICA artist collective) to SymbioticA at the University of Western Australia that I gained experience utilizing biological media in the production of art.

This was a transformative experience for me, deeply exciting and unsettling at the same time. I was challenged technically, ethically, and physiologically as I began to experiment with embodied technologies I had only ever read about in the past.

I was also challenged artistically, in that previously all of the strategies I had used in art-making were based on notions of representation. Where as in this instance I was an artist working in the realm of the real. It took a few years of hands-on bioart experience to come to terms with this transition.

In the early 1920s, Cubism helped physicist Niels Bohr to determine the quantum theory when he compared the behaviour of electrons with Cubist paintings. But, in your view what is the contribution of science to the arts?

Early models of Western science were rooted in various methods of observation and recording. A lot of the scientific research from that time is so closely linked to the artistic traditions of mimesis it can be difficult to separate the two.

Leonardo Da Vinci’s anatomical studies, Ernst Haeckel’s prints of diatoms, Kepler and Wollaston’s Camera Lucida, all mark significant scientific achievements as well as canonical contributions to visual history, and representational modalities that are still in use today.

More recently in the field of bioart, protocols and tools and experimental methodologies from the biological sciences are utilized by artists in the production of art towards aesthetic, political, and technical ends. I could go on. Examples of cross-contamination between the arts and sciences are endless.

Is art helping understand scientific/ecological issues or it is challenging what society understands about them?

Both.

What are your aims as a bio artist working in between science and art?

My aims have really evolved over the years. As I young artist I was enthralled with personal expression. Later on, I was driven by political critique and aesthetic experimentation. However, more recently, I find myself more engaged in celebration and wonderment of the varied verisimilitude of life in the lab and on this planet.

Certainly, there is a political drive to connect laboratory practices to notions of sustainability, resource management, and co-habitation. Also, I have become very interested in human traditions for the manipulation of life outside the hard sciences (hunting, farming, cooking, animal husbandry, etc.) as significant contributing voices in collectively determining our biotechnological future.

If you could visit a scientist’s mind, who would it be and why?

With the recent death of Oliver Sacks, I have been thinking a lot about his life and work. I have read most of his books over the years and always enjoyed the perplexing aesthetic, physiological, and psychological outcomes of the neurological disorders he describes.

The tone with which he writes often implies that these ‘disorders’ could also be understood as significant variations in human ability revealing the vast potentialities of the human brain and the wonderment of the natural world. I think an afternoon in his mind would be particularly interesting.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

Paperwork.

You couldn’t live without…

Oxygen.