Words by Lula Criado

Chromosomes are these turgid structures, found inside the nucleus of cells containing the basic bricks of living organisms’ DNA; but in the hands of Suzanne Anker chromosomes and science gain a new dimension.

In Anker’s work, they become a new paradigm in which the significance of DNA is not only about carrying genetic information. By incorporating scientific imagery and molecular biology concepts into her work, Suzanne Anker is not only representing the language of bioengineering but also raising awareness of the implications of genetic manipulation.

Suzanne Anker, visual artist, theorist and Chair of the Fine Arts Department at the School of Visual Arts (SVA) in Manhattan, has been fascinated with biological systems since her childhood when she witnessed the magical metamorphosis of a caterpillar into a butterfly.

She works in a variety of media, from 3D printing, MRI, digital sculpture, photography and installation to plants grown by LED lights and Petri Dishes.

Anker uses the imagery of science to create thought-provoking works in which she questions scientific practices such as animal genetic modification for scientific purposes. In her pioneering projects, Zoosemiotics and Codex: Genome, Anker enlarges microscopic images of the chromosomes to create calligraphic artworks using the iconography of chromosomes, representing the influence of genetics on contemporary art.

Her fascination with butterflies is reflected in her projects, MRI Butterfly and Butterfly in the Brain, in which she layers MRI brain scans, butterflies and chromosomes.

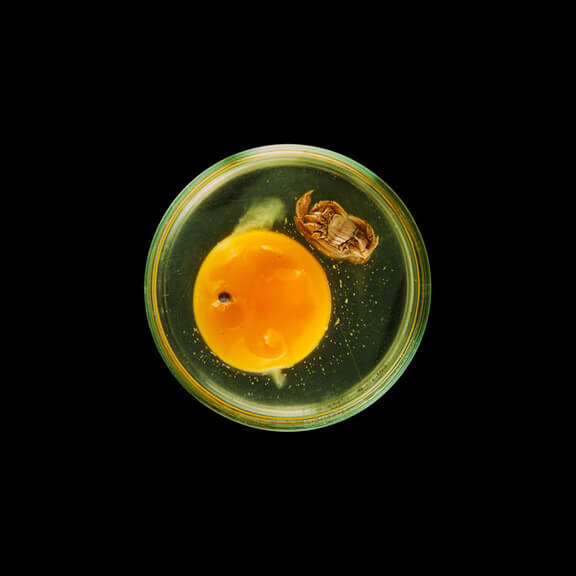

However, her latest projects, Petri’s Panoply and Vanitas in a Petri Dish, particularly challenge society’s current ideas of scientific practice. Anker appropriates the Petri Dish, a cylindrical plate often used in the laboratory for microbiology studies to culture cells and performs a series in which the boundaries between the binomial natural/artificial and the living systems/dead tissues are blurred.

In Anker’s work, the Petri Dish becomes a dynamic artistic medium acquiring a new symbolism that makes us question the world in which we live and also deeply provokes questions about ourselves and scientific discovery.

You are a visual artist working in the intersection of art and science, when and how did the fascination with biological systems come about?

My interest in biological systems stems from childhood experiences. In the back of the large apartment building where I grew up in Brooklyn, New York was a vacant lot. This tangled and chaotic property became my field station.

Overgrown with a panoply of weeds and arrays of insects, I became engrossed with butterflies. I began collecting caterpillars and milkweed and housed my specimens in shoe boxes.

I witnessed the metamorphosis of lowly crawling creatures into Monarch butterflies on many occasions. As a child, this transformation was magical and invisible, unlocking a primary interest in biology’s ethereal palette.

Erupting in the late 1980s, my specific interest in biological systems took the form of prints and sculptures that referenced genetics as a working paradigm. Employing the iconography of chromosomes, my work implied a connection between these hereditary markers and language forms. DNA is the way in which the body materially and conceptually writes itself.

Most currently, I am working with the tissue culturing of plants, growing vegetables with LED lighting systems and creating digital photography and computer-generated sculptures.

In the early 1920s, Cubism helped physicist Niels Bohr to determine the quantum theory when he compared the behaviour of electrons with Cubist paintings. But, in your view what is the contribution of science to the arts?

Science provides a data bank of images, concepts and even materials to the arts. Whether microscopic images or selected evolutionary theories, the structure of scientific classification shares a family resemblance with the history of art.

Although, based on differing epistemologies relative to subjective and/or objective enterprises, they both relate to the concept of “open text” as defined by Umberto Eco “Every work of art upsets the {aesthetic} code at the same time strengthens it too; by violating it, the work completes and transforms the code.” Such is the manner in which scientific paradigms shift as well.

From a material perspective science provides novel imaging devices, chemical compounds, synthetic pigments, and of course glassware, metals and even neon.

Is art helping understand scientific issues or it is challenging what society understands about them?

Art can be a vehicle for understanding scientific issues as well as a challenge to what the culture at large understands about genetic engineering, synthetic biology, and transgenics to name a few current practices. Making an image, fabricating an object or formulating an idea aids in understanding complex speculations and processes.

Art has the ability to tap into the cultural imaginary, that is, the fears and hopes of the populace. Art also is involved in social critique and can employ hyperbole to augment a visual argument., bringing to the fore how science is received by the lay community.

What are your aims as a bio artist working in between science and art?

As a liaison between these disciplines, I aim to underscore the role invisibility plays in both science and art. How can a novel use of a material create a new way of thinking? How can instrumentalized vision construct and reconstruct reality? How can artists employ the tools of science to make art?

Research into eco-friendly materials, the cloning of plants, and the use of a bio-printer to fabricate life forms is on my agenda. By creating projects employed in the service of Bio Art, it is possible to reach a wider audience for educational and communication purposes, in this golden age of biology.

If you could visit a scientist’s mind, who would it be and why?

Simon Fishel is a pioneering scientist in the field of in vitro fertilization. He worked alongside Robert Edwards in Cambridge (UK) to create the first test tube baby, Louise Brown on July 25, 1978, making medical history.

IVF treatment was originally looked upon with scorn, as a form of playing God. His revolutionary work seemed to be against all odds. However, his work was instrumental in a number of ways. He discarded test tubes and replaced them with Petri dishes showing that embryos respond to environmental conditions.

In addition, he pioneered techniques for male infertility. Currently, he works in Nottingham, England where he employs an embryoscope as a device for screening embryos before their implantation. Embryos are put into the machine and their development is recorded over a period of five days.

As they unfold in time each stage of development is pictured from day 0 through day 5. Before the advent of the embryoscope, there was no clear way to grade embryos as to their viability. Reproductive technologies, embryos, and fetuses are all trigger points for the public at large.

Dealing with life itself is courageous, if not dangerous. Weighing in on how technologies are changing the human condition, reproductive or otherwise, what was thought impossible is now on the horizon. Such techniques require fertilization to occur outside the womb for later transplantation.

What was once a private affair of sexual reproduction now takes a scientific turn, in which sexual contact is absent, heralding an ongoing asexual revolution.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

The chief enemy of my creativity are petty nuisances. They are a real bother which upset the delicate balance needed for visionary work. Creativity requires uninterrupted rumination and daydreaming on a repetitive basis. Creativity lives in a nether world where fact and fiction meld.

You couldn’t live without…

My imagination.