Text by Ana Prendes

Among its many impacts, the covid-19 pandemic has challenged our eagerness to move freely and safely through towns and across borders. This year inside has flourished our capacity to imagine how some futures might be composed to prevent others.

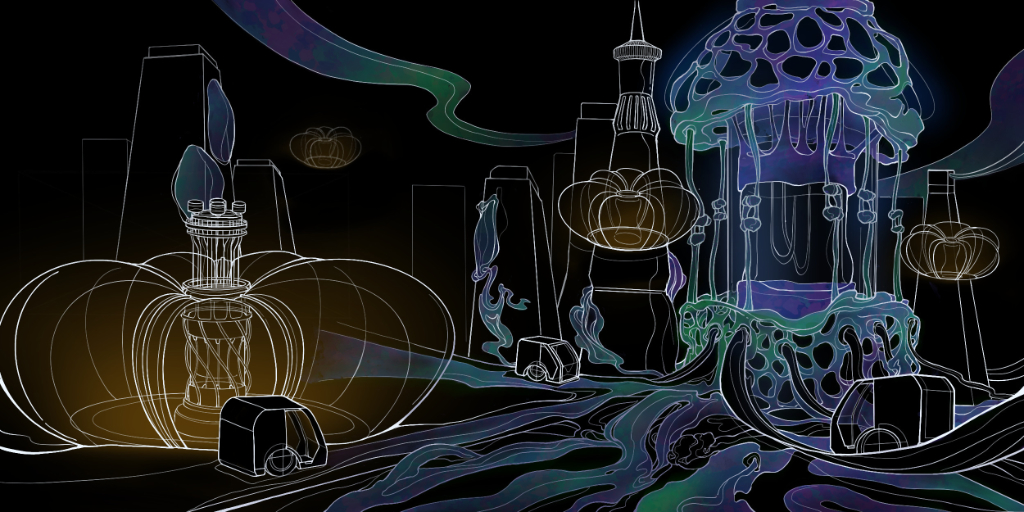

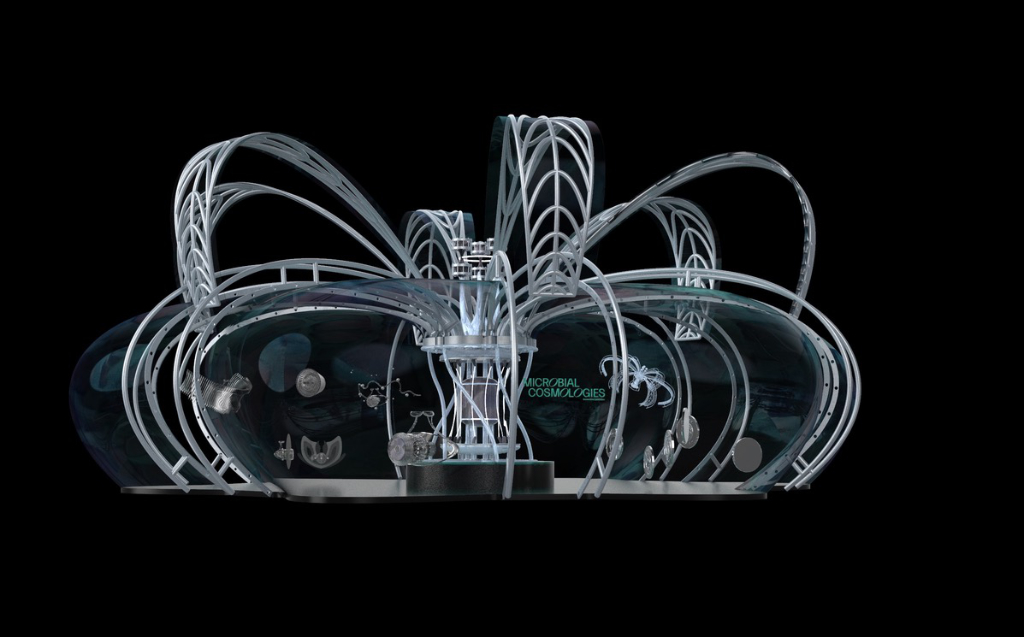

The immersive project Microbial Cosmologies imagines a Future of Mobility with a distribution system of bodies, goods, and information built around the microbial world–while redefining our sense of identity, borders, and citizenship through our microbiome.

Designer and Assistant Professor at RISD Anastasiia Raina led the multidisciplinary team of RISD’s students behind the project –Yimei Hu (BFA, Jewelry & Industrial Design), Danlei Huang (MFA, Industrial Design), Georgie Nolan (MFA, Graphic Design) and Meredith Binnette (BFA, Film, and Animation)– as part of the university’s research collaboration with the Hyundai Motor Group.

After a collaborative research phase into symbiotic mobility, biological design, bioenergy sources, and mobility justice, the five designers generated narratives to explore this extensive scientific research. What new mobility solutions will emerge from the pandemic, who will benefit from these solutions, and who will be left behind? Our team considered an all-encompassing approach that could transform and adapt to the pandemic’s evolution and the new knowledge we gained with emerging scientific research. Raina explained.

The generated narratives underwent multiple iterations in speculative fiction writing, sketching, and prototyping, where each team member contributed with their skills before finally building the Microbial Cosmology.

From Resource Distribution Vehicles powered by a Symbiotic Bioengine, Microbial Passports and a Microbial Data Bank to centralised governance by the Global Gut System, Microbial Cosmologies present new approaches to a global bio-economy, a biopolitical state and microbial-inspired mobility, creating technologies of inclusion and microbial diversity as a way to build co-immunity.

Could you tell us a bit more about the intellectual process behind Microbial Cosmologies? What’s the story and symbolism behind the name of the project?

Our research team set out to develop new ways of thinking and making by looking at how organisms and systems have evolved and adapted to their surroundings regarding transport and mobility. Having witnessed how a virus the size of 0.125 microns could bring countries, economies, cultures, and education to a standstill, we imagined a future entirely built around the most successful organism on the planet.

Our human tendency to underestimate microorganisms and unwillingness to change our lifestyle has led us to chronic epidemics and worldwide viral outbreaks that will only worsen with the increase in population and access to new modes of transportation.

This is the time for rethinking what mobility means in the age of pandemics and how the mobility distribution of bodies, goods, and information is now carefully choreographed by the invisible microorganisms around us. Instead of fighting a losing battle with bacteria, viruses, and now informational epidemics, we imagine a paradigm shift in ways humans can coexist with each other and other nonhuman species, including pathogens.

Microbial Cosmologies (the title originates from Greek κόσμος, kosmos “world” and -λογία, -logia “study of”) is an immersive project where we imagine a future of mobility that is entirely built around the most abundant and successful type of organism in our biosphere—the microbe. With this project, we are proposing a shift from an anthropocentric to a biocentric perspective in design.

By placing the microbe at the centre of our project, we challenge and decenter our human exceptionalism and, with it redefines our sense of identity, borders, and citizenship through the human microbiome. We imagine new mobilities with cyborg natures, moving away from fossil fuels to symbiotic machines powered by microorganisms. And we explore the global bio-economy, micro-biopolitical state, and biosafety to create technologies of inclusion and microbial diversity to build co-immunity.

You use the term ‘symbiotic design’. How would you describe this concept?

Design routinely constructs radical inequalities; one group’s capacity is expanded at the expense of another. Symbiotic Design explores the entanglement of symbiotic interspecies relationships that continually adjust according to requirements and environmental conditions. Symbiosis is not an idealised relationship but a process in which the species continuously negotiate the use of natural resources in a dynamic balance that allows all to survive.

Symbiotic Design seeks to develop platforms facilitating cross-species collaboration—an ecological interaction between two or more species. Each species has a net benefit, allowing new symbiotic mutualisms to emerge, particularly those that do not exist in nature. Symbiotic Design aims to identify standard value systems and compatible goals these species could pursue together and support nonhuman participants on their terms.

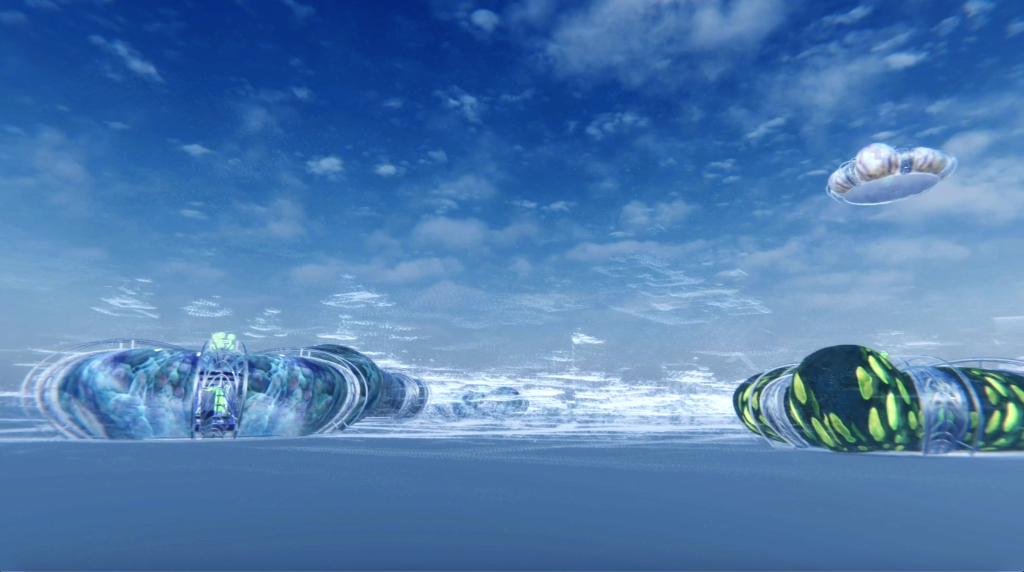

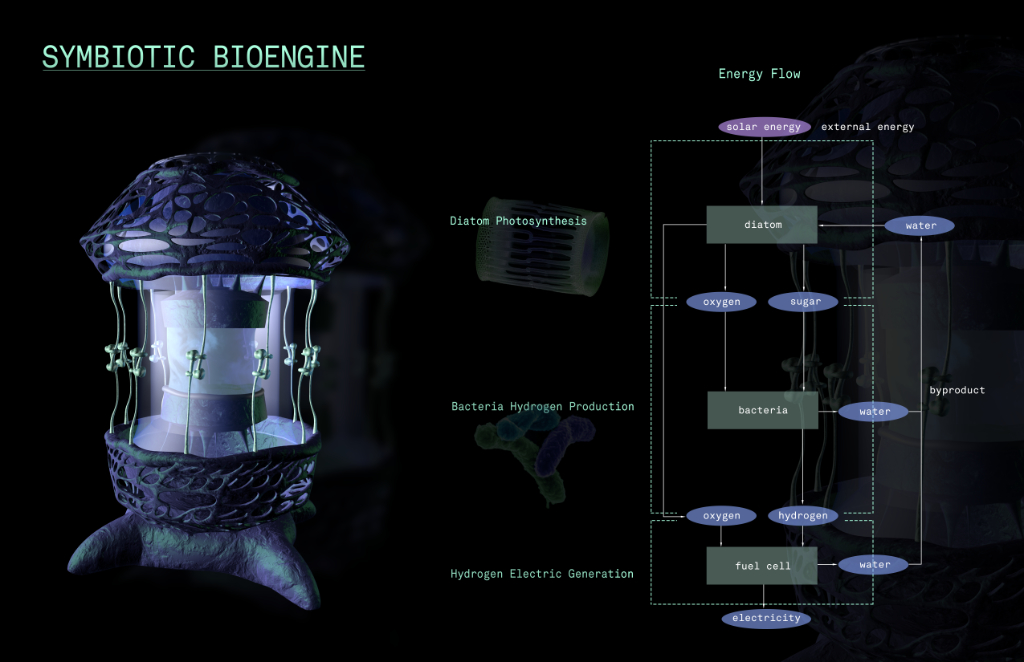

For example, our Resource Distribution Vehicles are powered by a Symbiotic Bioengine. The engine is a platform that creates a biofeedback loop that combines photosynthesis, biohydrogen production through metabolism, and hydrogen-electric generation. The engine, which sits in the centre of the vehicle’s flexible structure, allows each RDV to be self-sufficient. Symbiotic Bioengine’s structure consists of:

1. Diatom Photosynthesis. In the engine model, diatoms play the role of one symbiont. Diatoms are one of the largest and ecologically most significant groups of microorganisms on Earth. They are abundant in aquatic habitats, forming an essential part of the natural food web. Moreover, diatoms make a tremendous contribution to the global carbon economy by turning carbon dioxide into organic carbon and, in the process, generating oxygen. Living in the top layer of the engine’s vertical structure, diatoms produce oxygen for the electricity generator and provide sugar for the hydrogen-producing bacteria.

2. Bacteria Hydrogen Production. Hydrogen-producing bacteria, including several genera like Clostridium, Enterobacter, Klebsiella, Citrobacter, and Bacillus, can consume sugar and release hydrogen gas when digesting. The only byproduct of the metabolism process is water.

3. Hydrogen Electric Generation. The bio-hydrogen gas produced by bacteria is funnelled into a fuel cell. The hydrogen fuel cell produces on-demand electricity by combining hydrogen and oxygen atoms. The hydrogen reacts with oxygen across an electrochemical cell to produce electricity, water, and tiny amounts of heat.

The Bio-State is sorted by The Global Gut Technology Operating System and with each diegetic prototype. Could you describe a typical day for someone living in this world?

In our Bio-State, the microbiome defines our identity and citizenship. The world runs on Global Gut Technology, where the energy produced from microbial biofuels harvested from the environment and human waste powers adaptive techno-natural machinery.

Economies revolve around cultivating a unique human microbiome currency, and synthetic biology is used to program and govern this microbiopolitical state. Post-pandemic society has embraced artificial evolution and dramatic shifts in urban planning, contactless habitation, citizenship notions, biometric monitoring, and quarantine communities.

Location, access to work opportunities, culture, and education, are no longer the prime concern of the Bio-State citizens since goods are equally distributed throughout the area. Large self-sufficient communal spaces drift through the airspace containing access to all vital resources utilising the air currents and wind patterns.

Besides being used for citizen transport, a Resource Distribution Vehicle also harvests and collects aerobic microorganisms for research purposes. Combined with the information supplied by The Global Gut Operating System, the soft skin-like architecture of the vehicle contracts and expands to accommodate different numbers of passengers or adapts to be suitable for quarantine by dividing into several isolated areas with alternative entry and exit points.

A citizen of our world spends each day feeling part of a much larger, all-encompassing ecosystem of human and nonhuman life. From the moment they wake up, they participate in The Global Gut Technology Operating System, a techno-natural hybrid network that connects all things; humans, vehicles, cities, climate patterns, algorithms, and organisms.

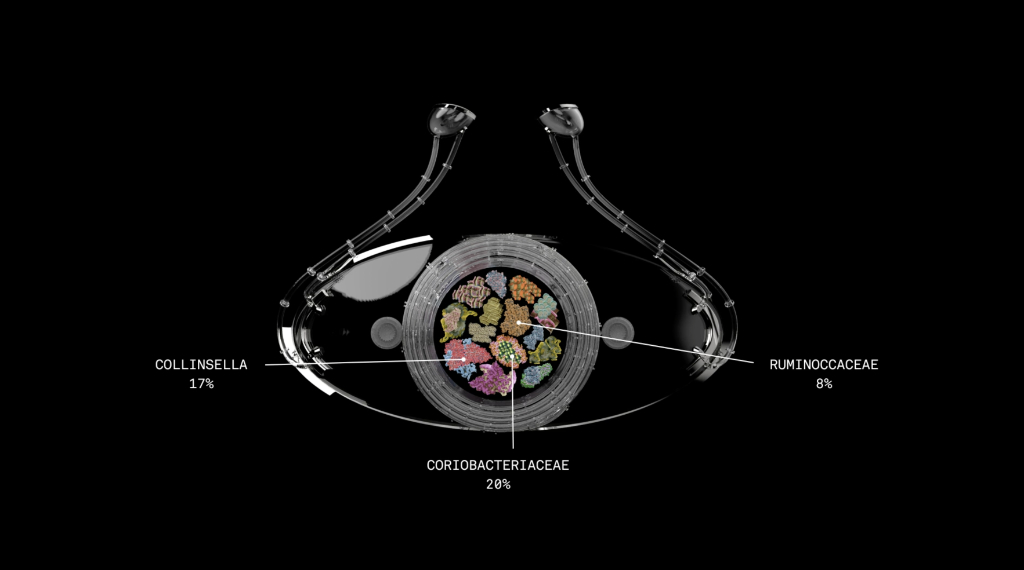

Part of the day would be spent cultivating, harvesting, and trading personal strains of bacteria from their waste to fuel our bio-economy. By linking gut health directly to income opportunities, the state allows citizens to prioritise their well-being. A Microbial Data Bank allows citizens to upload their microbiome data to the System in exchange for GutCoin.

This coin is one of the main circulating digital currencies that citizens can generate, deal with, and spend on purchases like rides on a Resource Distribution Vehicle. The Data Bank is part of the ecology of devices interconnected with the System. It collects and stores citizen microbiome data, which powers the Bio-Economy, Symbiotic Engine, and Microbial Masks.

Biosecurity, which consists of collecting and sharing microbial data, has become the norm. Citizens have realised the existential risks of ignoring the invisible virus and putting effort towards monitoring and learning about new mutations and changes occurring in the environment—maintaining a harmonious balance in the community for stronger immunity to potential threats.

The microbiome’s informational code is the ultimate commodity. To ensure equitable political power, citizens have complete control over the production and distribution of biocodes. Citizens control their biodata and selectively contribute to the Global Gut System, knowing that they will benefit from it. Contributing to locally stored community databases allows communities to have regional control over their biosecurity.

There’s a vast scientific knowledge behind the prototypes. Coming from a design background, could you tell us a bit more about the design process?

As a multidisciplinary team, we combined a number of varied design processes throughout the project’s development. Starting with an intensive and collaborative research phase, we generated initial ideas that helped us to explore scientific research through narrative. Based on the key findings, we established a list of “what if” speculative scenarios.

A paper by David Smith on Intercontinental Dispersal of Bacteria and Archaea by Transpacific Winds [1] introduced us to aerobic bacteria in the troposphere, hitching rides from Asia through the Pacific Ocean and landing in North America. Immediately we began examining the bacterial trajectories and creating a vehicle to accommodate the stowaway bacteria. We collected it for research (since tropospheric bacteria is the least studied) and cultivated it for microbial biofuel that would power the vehicle itself.

Later, after learning about geography-specific variations in microbiota [2] and the fact that a person’s native microbiome westernises immediately after their immigration to the US [3], we asked, “What if a person’s citizenship was based on their gut microflora?”

The narratives generated from those scenarios underwent multiple iterations in speculative fiction writing, sketching, and prototyping. Each team member contributed her particular skills before finally refining and building the Microbial Cosmology. Because our project responded to a real-time situation, the research and scientific discovery were ever-evolving, and our design process had to accommodate that.

One of the research goals was to define what it means to be inspired by Nature in the age of gene editing and information technology. Design inspired by Nature has mainly focused on biomimicry, but our biocentric approach required us to invent new methodologies for working with Nature. It is extremely important that we are not only inspired by Nature or work with Nature as a material but that objects that we create equally benefit Nature. Each diegetic object we created represents these two different methods of working with Nature.

Symbiotic Design — this method combines Nature+Technology to create living machines that enable collaboration across two or more nonhuman species that belong to different ecosystems, facilitating the emergence of new symbiotic mutualisms and rehabilitating the effects of the anthropocentric turn.

Artificial Nature —Synthetic Biology for Sustainable Design. Biotechnology has a profound impact in medicine, agriculture, and manufacturing, where we can engineer sustainably grown organic materials and living organisms to metabolise waste.

Global Gut Technology is a result of the Artificial Nature model. It is a speculative operating system that combines microbes—the most abundant organism on the planet with the mycelial network—the most extensive organic information and resource distribution network on the planet, with machine learning to connect all living organisms and algorithms in one self-regulating network. The Global Gut network algorithmically governs the world, economy, resource distribution, and human mobility.

Dissemination of the research was also a crucial part of this project. Due to COVID, our physical exhibition in Seoul was cancelled, so we created a VR exhibition space and a walk-through video to show all of the prototypes. We also made a series of AR Snapchat filters for our Resource Distribution Vehicle and Masks to engage a wider audience. To share the research process, our team presented a project at Stanford LASER talks and created a Co-Immunity prototyping workshop for Columbia Digital Storytelling Lab, where we illuminated the collective experiences through mask design to re-building a sense of community in the post-COVID world.

The microbial passport can’t be more timely. Do you envision any of these prototypes leaving the speculative territory to be implemented?

The unprecedented nature of the Coronavirus has divided cities and countries based on the management of their immunological containment response. Wealthy countries such as the US and Western Europe have purchased most of the world’s vaccine supply, leaving less advantaged countries without a chance to curb the pandemic where it is most needed. Vaccination passports are now threatening to become a technology of exclusion, where only citizens of wealthy countries will have the opportunity to travel.

In contrast, we built Microbial Cosmology based on the co-immunity response, where the Global Gut Operating System encourages the diversification of the local microbiota by introducing a foreign microbiome to enhance the immune response of its citizens. Historically immigrants and foreigners have been associated with contamination, and unfortunately, COVID-19 only fueled this deep-seated xenophobia around the world.

With our Microbial Passport, we wanted to challenge the ideas of purity and contamination in the notion of citizenship and national borders and showcase that our collective immunity can become stronger through microbial diversification. Microbial Passport defines nationality, citizenship, and immigration entirely on a person’s microbiome composition. The data is extracted from a traveller’s breath test, and Global Gut technology can identify a person’s last point of departure based on geographically-specific variants.

Speculative Design can be used as a lens to see implications for the future. But how do you imagine the future of speculative Design? How is speculative Design impacting our future?

Just like speculative fiction is not about predicting the future but rather constructing an imagined future to comment on the real present, Speculative Design describes the existentialist complexity of the contemporary world by constructing multiverses in which we explore plausible, possible, and probable responses to issues at hand. We create proposals for the future that we can all experience. This experience might help us decide whether we want these scenarios to come true after all or imagine new futures together.

However, if, until a year ago, Speculative Design was mostly limited to a circle of inventive minds in art schools, the urge to imagine, predict and simulate the post-pandemic world’s uncertain future has now become a widespread effort. The exciting part of partnering with Hyundai is that we could introduce speculative thinking to a leading automotive manufacturer, which will hopefully produce more equitable and sustainable futures.

There seems to be a rising interest in our need for a holistic approach to interspecies relationships. This is traceable to the influential thinking of authors like Donna Haraway or Bruno Latour, which has significantly influenced speculative Design. What is that these relationships illuminate about our present moment and our future?

Speculative Design is a space where Design, Science, and Philosophy merge, a platform to ignite imagination about our possible futures. Design as a discipline is undergoing a tectonic shift, reexamining its histories and first principles. A similar effort is underway in Science and Philosophy. All current engagement with Nature derives from the professionalisation of the sciences that relay botanical knowledge as fixed entities, absent of agency, enduring only for human advantage.

To make way for viable futures, we need to align with another kind of knowledge production that is collaborative and transdisciplinary. One that asserts equal agency for nonhuman subjects and dismantles dualisms and boundaries, particularly the boundary between organisms and machines, humans, and technology. Donna Haraway’s work is central to illustrating this hybrid vision of humanity itself, challenging the perception of the human and Nature as universal and hegemonic so vaunted in humanism.

To create viable futures, we need to define new relationships for mutual survival and explore the potential of unfamiliar strategies of “making kin,” as Donna Haraway advocates. Instead of using natural systems for our gain, we need to invite them to be our intellectual and emotional partners in a quest for a sustainable environment for all of us to thrive within.

In my practice and pedagogy, I introduce nonhuman perspectives as an active part of artistic knowledge production. My students and I explore worlds beyond human perception that occur on macro, micro, and molecular scales and work towards post-anthropocentric modes of artistic making. By decentering the human and introducing the term collaboration into our work with Nature, we significantly expand our understanding of the multiple agencies, dependencies, entanglements, and relations that make up our world. The crucial point is to learn what new types of practices can emerge in the reciprocal relations or co-production between organisms, algorithms, and humans.