Text by Tuçe Erel, Jenny Alten & Udo Koloska

Echoes of the Future: Artistic Interventions is a group exhibition featuring works by Cécile Wesolowski, Jenny Alten, Käthe Wenzel, Patricia Detmering, Swaantje Güntzel, and Udo Koloska at Biosphäre Potsdam. Tuçe Erel curates the project in collaboration with artifact e.V. and parallel to the conference Myth, Ritual, and Practice for the Age of Ecological Catastrophe that took part last May 17-19, 2024, at the University of Potsdam, Germany.

The exhibition focuses on narratives and aesthetic practices in the environmental crisis that question and update the myths and rituals of past and present culture. Who narrates and which politics of the sayable determine the present? What do rituals and culture mean in the midst of a progressive environmental crisis caused by human activity? The artists create personal echoes beyond narratives of the end of the world or technological progress.

Facing the systemic failure to adequate reactions to the climate catastrophe, as German sociologist Jens Becker describes, The impositions on the population and the resulting fear of loss lead to political dissatisfaction, which is mobilised by the respective opposition for election campaign purposes. Cognitive psychologists show that people find it particularly difficult to cope with expected losses and focus their actions on avoiding them. In a political system that relies on the mass loyalty of the population in elections, the political implementation of effective climate protection remains difficult, at least to the extent that it does not take place in the time available to achieve the climate targets that have been set [1] the artists’ reactions in their aesthetic practices are diverse, sometimes contradictory but never hopeless.

The exhibition location went through many transitions: The land on which it was built, which was formerly a military training ground, became the relic of the Federal Horticultural Show 2001 and transformed into the human-made rainforest Biosphäre Potsdam opened its doors to the public in 2002. Working with this transformed site urged the curator and the artists to crystallise their questions and bring various mediums and interventions to the jungle.

The first artwork, Leviathan by Kaethe Wenzel, is a six-meter-long bone-sculpture hanging at the entrance to the tropical rainforest. Kaethe Wenzel’s sculptures are visceral commentaries on consumer behaviour and the way we deal with the more-than-human world. Inspired by Thomas Hobbes’ Leviathan (1651) and the term Capitalocene coined following Andreas Malm by Jason W. Moore [2] and Donna Haraway[3], Wenzel’s Leviathan closely examines concepts of nature, longing for nature, and consumption. Hobbes’ Leviathan discusses the power of masses and collectives and constant human aggression—problems that, in the face of the sixth extinction of species, climate change, and the alienation of the human world from the non-human world, are everywhere, their social, economic, and ecological effects only just beginning to show.

Wenzel’s Leviathan is made from animal bones collected from restaurant bins and roadkill. It is shaped like a whale in reference to a biblical sea monster punishing humanity and symbolises the exploitation and near extinction of the species. Wenzel’s bone sculptures critique our detachment from nature and explore mass consumption and the use of animal bodies. They depart from historical corset techniques and modern fashion and evolve into exoskeletons. Her Bone-Birds, around thirty bone sculptures, appear in the tropical jungle, symbolising escape and freedom.

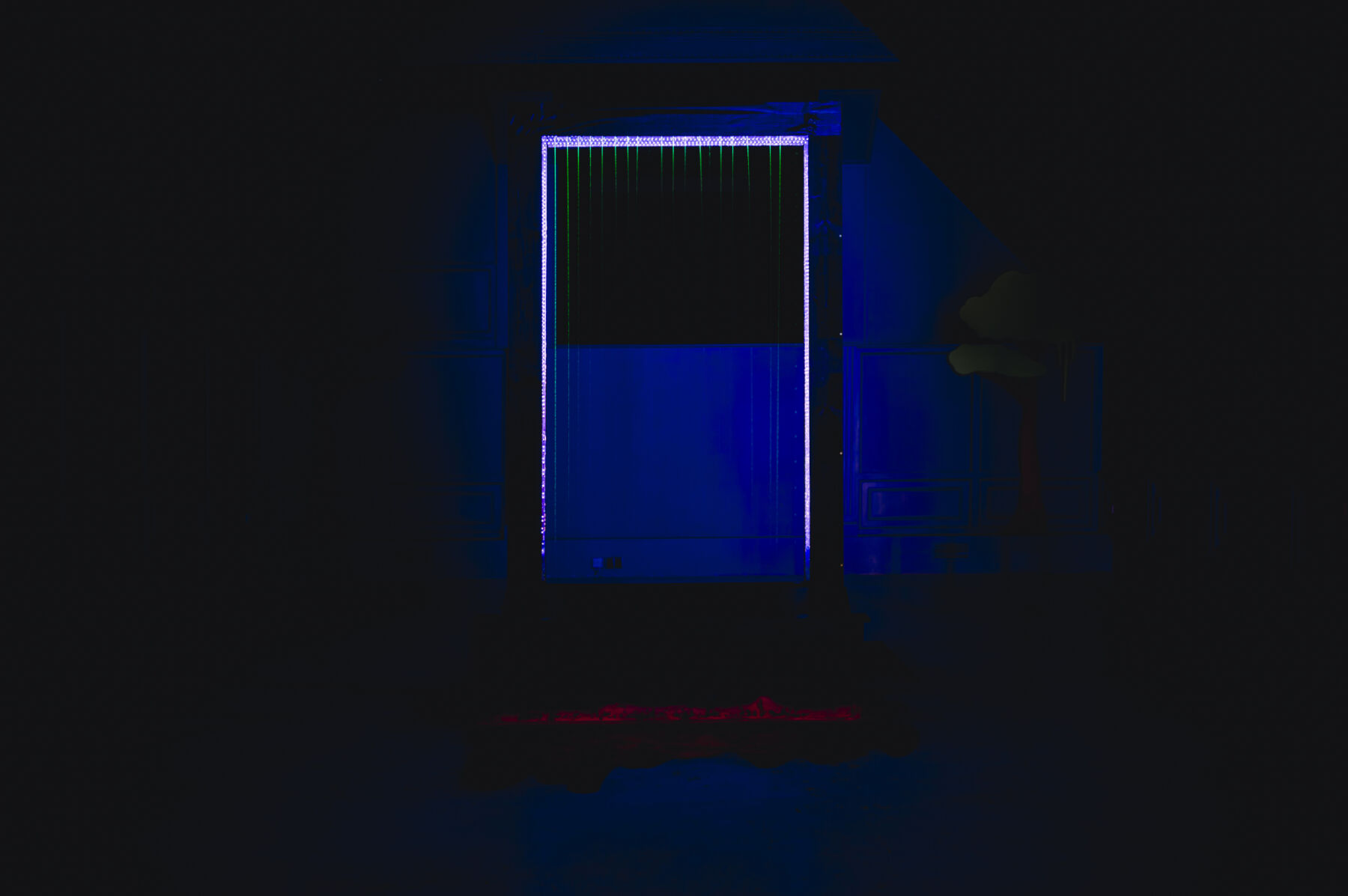

The second artistic intervention is located at the entrance of the tropical hall. It is a sound and light installation by Udo Koloska titled Afterlife. The reference point of the work is the large-scale loss of forests in the Harz Mountains and the associated transformation of the local ecosystem. Around four out of five spruce trees in the Harz National Park have died due to drought, monoculture, and bark beetle infestation. Although there have been extensive attempts and successes in reforestation, there is still no trend reversal in sight. In place of the dead spruce forests, new vegetation is emerging from the roots, seeds, materials, and intertwinings on site.

This national park was a regular site that Koloska visited with his family as a child. He has been witnessing the massive deforestation of the park. Koloska did the field recordings in the Upper Harz near Schierke in 2023 and 2024. In his installation, he uses the audio recording to light pulses in reference to the 17th century’s Galvanism idea and early Romantic philosophy. The galvanic experiments with electricity and muscle contractions led early Romantic natural philosophy to postulate electricity as a life force. Such an approach was based on organic materialism, which no longer distinguished life and spirit from material processes in principle and therefore questioned, among other things, the superiority of man on metaphysical grounds.

From this starting point, he delves into the New Materialist methodologies and theories to connect nature and culture as Haraway’s concept of nature-culture [4] in one word as a statement in contrast to centuries of anthropocentric thinking, agency encompasses all things in the universe, whether plant, animal, human, river or mountain.

Depending on the dryness and wind, sounds of barkless trunks and wood arise in the dead forest areas. Through changes on the time axis, rhythmic structures emerge from the field recordings – an amorphous, endless rhythm. The spacial installation made of wood, pebbles, lights and sound devices ties in with the surreal sound images that accompany the transformation of the local ecosystem and creates a projection surface for the ghostly apparitions and phantasms of the future, the transformation of the ecosystem, the loss, the memento mori or the dance of survival. According to Jacques Lacan, the real appears as something repressed that does not occur in our narratives of the world. Here, it appears as destruction or as an uncontrollable transformation.

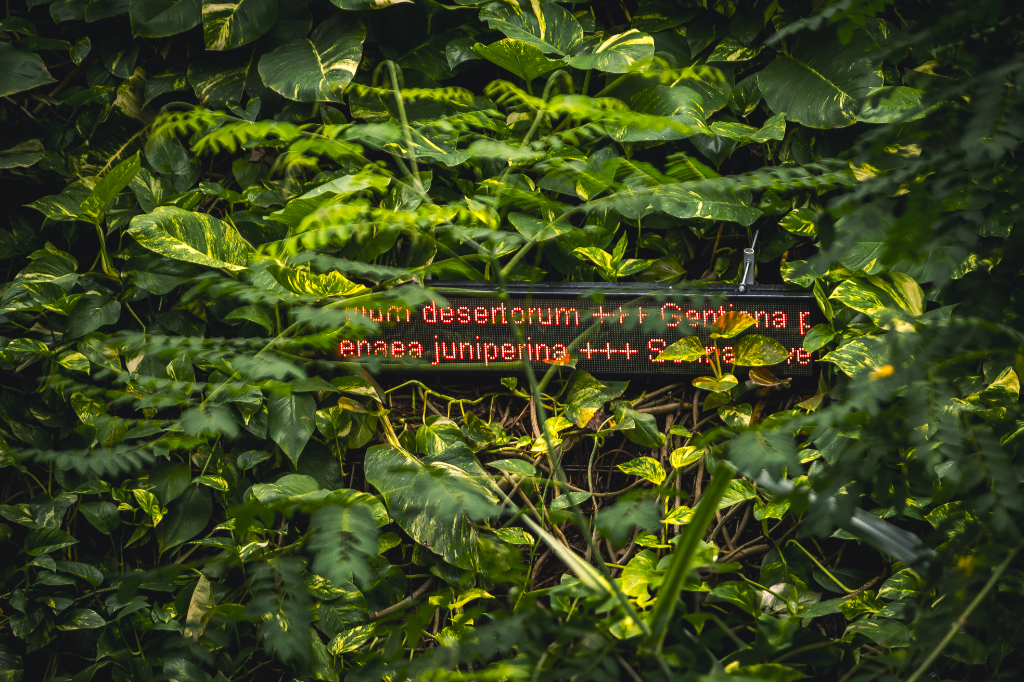

When the visitors use one of the wooden bridges connecting the 5000 square meters and 20-meter-high building, they can encounter Swaantje Güntzel’s interventions over the ivy surface covering the concrete walls. Her work reflects on the fragility of biodiversity. A digital panorama focuses on the valuable seeds stored in the Svalbard Global Seed Vault on the Norwegian Island Spitsbergen.

Swaantje Güntzel has been investigating the radical changes humans have been inflicting on nature for over twenty years. Güntzel’s site-specific work consists of an LED panel showing the list of seeds stored in the GLOBAL SEED VAULT. As the official website describes, the Seed Vault safeguards duplicates of 1,301,397 seed samples from almost every country globally, with room for millions more. Its purpose is to back up genebank collections to secure the foundation of our future food supply against the loss of seeds in gene banks due to mismanagement, accidents, equipment failure, funding cuts, war, sabotage, disease, and natural disasters. The existence of this seed vault is a reaffirmation of human intervention over nature in positive and negative ways at the same time. It is protecting diversity but reduces accessibility at the same time.

This ambiguity is also true for the Biosphäre itself —its vast variety of species and the possibility of encountering a far away ecosystem on one hand and its state-funded energy wastage with the costly entrance fee barriers are controversially discussed amongst Potsdam locals. Figures are not publicly available. But the following issue indicates the scale: By lowering the temperature after the full-scale invasion in Ukraine, the city saved 200.100 kWh and promoted the place as a possible warming hall for people who could not heat their apartments. This double life of the Biosphäre became more visceral when it housed nearly 100 Ukrainians, many of whom now work at the attraction site.

Passing further through the jungle, one arrives at Patricia Detmering’s partly physical, partly augmented reality installation From a Wild Weird Clime. “L̾a̾i̾c̾u̾” is the protagonist of a book by Patricia Detmering. It depicts a modern mythological creature that eats dreams. This creature manipulates people’s dopamine and serotonin levels to gain entry into their bedrooms, where it controls their dreams and distorts their perceptions. L̾a̾i̾c̾u̾ thrives in bland, scalable environments that alienate the human psyche, leading to a fragmented global community. The myth raises questions about new rituals needed to balance dopamine levels and live more honestly, helping humanity escape L̾a̾i̾c̾u̾’s grip.

For the exhibition, several drawings reproduced on translucent plexiglass are shaped over the stones, thus organically merging with the exhibition site. These drawings of L̾a̾i̾c̾u̾ also have a digital presence as an augmented reality that can be accessed over mobile phones. Through the screens and permeable surfaces, she discusses the physical and virtual, visualising realities, stories, and myths floating around similar to biochemical agents.

The pathway in the tropical jungle leads the audience to an artificial waterfall, where Jenny Alten’s installation, *****cool, dunkel, wasserdicht, hangs. The installation consists of outdoor tents as a critique of consumer culture, the growing outdoor sector, and people’s tendency to connect with nature using materials that harm nature. According to Alten, the term nature religions and their alleged closeness to nature is instead the attribution of Europeans served to control and demarcate. It continued the Christian-claimed discontinuity between humans and nature. The current desire to be close to nature treats nature again as something separate from which we protect ourselves with high-tech equipment.

On the one hand, the environment and the milieu are idyllized by the back-to-nature trend. On the other hand, the narrative of the foreign is invoked, from which we could separate ourselves with semi-permeable membranes. Yet the ever-new technologies and coatings protect us from the cold, wet, light, and touch. We still do not see ourselves as part of an environment.

The demand to import rituals from indigenous people as healing techniques and alternative medical treatment also repeats a questionable attitude because all religions are cultural creations and thus mark a distance from the nature that surrounds us. Émile Durkheim, Carl Strelow and Karl-Heinz Kohl, for example, also describe the friendliness of nature in prehistory as a retroactive attribution. Nature religion, as a designation of the religion of the peoples who were formerly called primitive peoples and in contrast to the „cultural“ religions, can be evaluated positively: as agreement/harmony with ordered nature, from which man has distanced himself through historical development (hence Rousseau: back to nature), or negatively: nature as something that man has to overcome through culture (Hobbes: homo homini lupus est [5].

As Levi-Strauss examined in The Totemic Illusion (1962), attitudes that are incompatible with the demand for discontinuity between nature and man, which is essential to Christian thought, are thrown out of our world like an exorcism. It is not only Christian thinking that asserts the separation of man and nature. In Islam, too, people are described as descendants of God and separated from the environment. With her work, Alten disagrees with the current approach in contemporary art to investigate rituals as a source of healing the separation between humans and their environment. According to her, all religions, including their practices, rituals and teachings, mark human action and the separation from nature as cultural creations. Appealing to a religion given by nature is an illusion.

After passing the waterfall, the pathway leads to an elevator and to the exit, where the audience finds themselves in the research room of the Biosphäre Potsdam, where the artist Cécile Wesolowski’s light and sound installation Time waterfall is installed. She uses a stroboscopic light technique conceptualised by Harold “Doc” Edgerton, an American electrical engineer and photographer noted for creating high-speed photography techniques. He developed and improved strobes and used them to freeze objects in motion so that they could be captured on film by a camera.

The ‘Piddler’ machine he created more than 50 years ago uses a stroboscopic technique to form optical illusions of levitating water droplets, slowing the downward flow of water as well as reversing the flow of water to move upwards to defy the laws of gravity. Based on this technique, Wesolowski’s light installation is a visual illusion of a reverse waterfall. The drops of water appear floating in front of the human’s eye, falling slowly or even flowing upwards. It looks as if the water is overcoming gravity. The installation reacts to the perception of time, how it can liquefy, and how, through digital manipulation, it can even run backwards.

The artists in the exhibition critically deal with the relationship between nature and culture in relation to mythologies and religion. As David Bohm discussed in the text Participatory Thought and the Unlimited [6] religious and cultural practices are shaped by the nature and environment of the societies in the early human cultures, called ‘participatory thought’. However, ‘literal thought’, such as scientific knowledge, created a transformation and reinforced the dichotomy of human vs. nature. Participatory thought was aligned with the notion of co-existing with nature and the environment, whereas literal thought defined nature as a limitless source to be exploited.

It is an illusion to reverse the damage that we cause; gestures like the seed vault pretend to prepare the next generations for possible catastrophes instead of preventing further damage with fundamental changes in capitalist and consumerist systems. In conclusion, Echoes of the Future: Artistic Interventions serves as a compelling exploration of the intricate relationship between humanity and the environment through diverse artistic expressions.

The exhibition questions the myths and rituals that have shaped our cultural responses to ecological crises and invites us to reflect on the complex and often contradictory human interactions with nature. By situating these works within the artificial landscape of Biosphäre Potsdam, the artists underscore the ongoing tension between cultural practices and environmental realities. Their interventions challenge us to rethink our role in the ecological narrative and inspire a deeper, more critical engagement with the pressing issues of our time.