Text by Anne Murray

Éva Mayer’s exhibition at Ani Molnár Gallery in Budapest, curated by Lili Boros, delves into the limbic space of fertility, hope, and loss and its relationship to the female identity in contemporary times. Exploring this Terra Incognita, she discovers solidarity and kinship with other women through incorporating their words and reactions into her installations.

The curator, Lili Boros, explains the genesis of the installation at the gallery, My goal was to articulate that the starting point of the works was the processing of a personal trauma on a social level. This joint viewpoint or source of works is very typical for Éva’s art. Indeed, loss, trauma, and renewal have been at the center of Mayer’s works over the years. This exhibition is another iteration including some of the previously considered aspects of these human exigencies and some new ones.

Mayer responds to my questions about these elements of her work in an email exchange, How can a woman feel when she finds out that she doesn’t or just has a hard time having a child? Despair, hopelessness, frustration, helplessness, loneliness, isolation, sadness, anger, anxiety, panic… Today, every fourth to fifth couple in Hungary struggles with infertility.

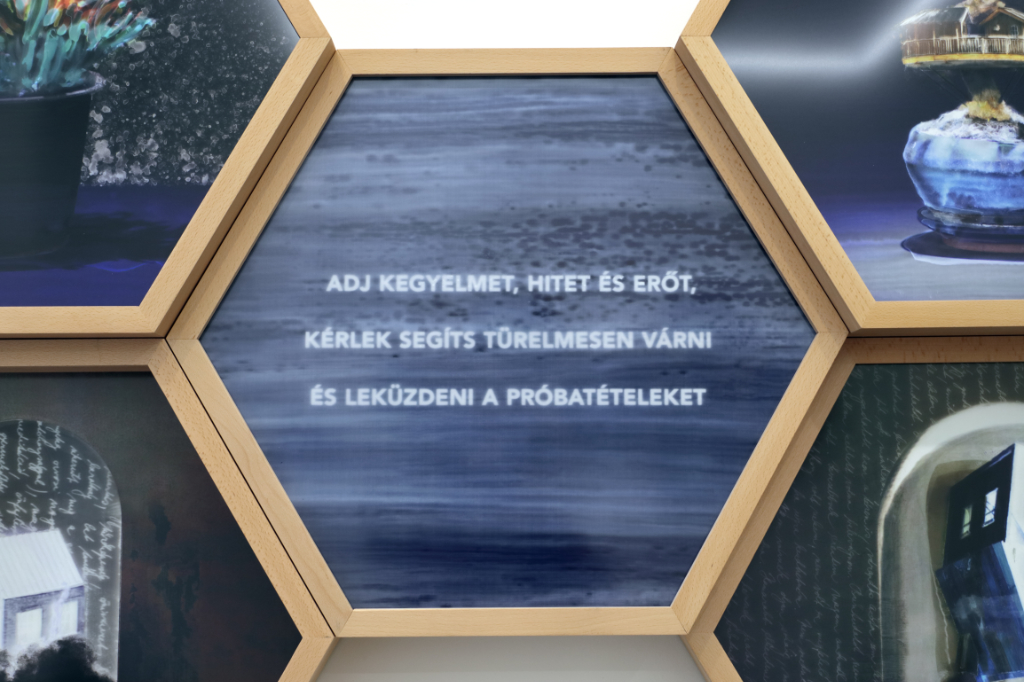

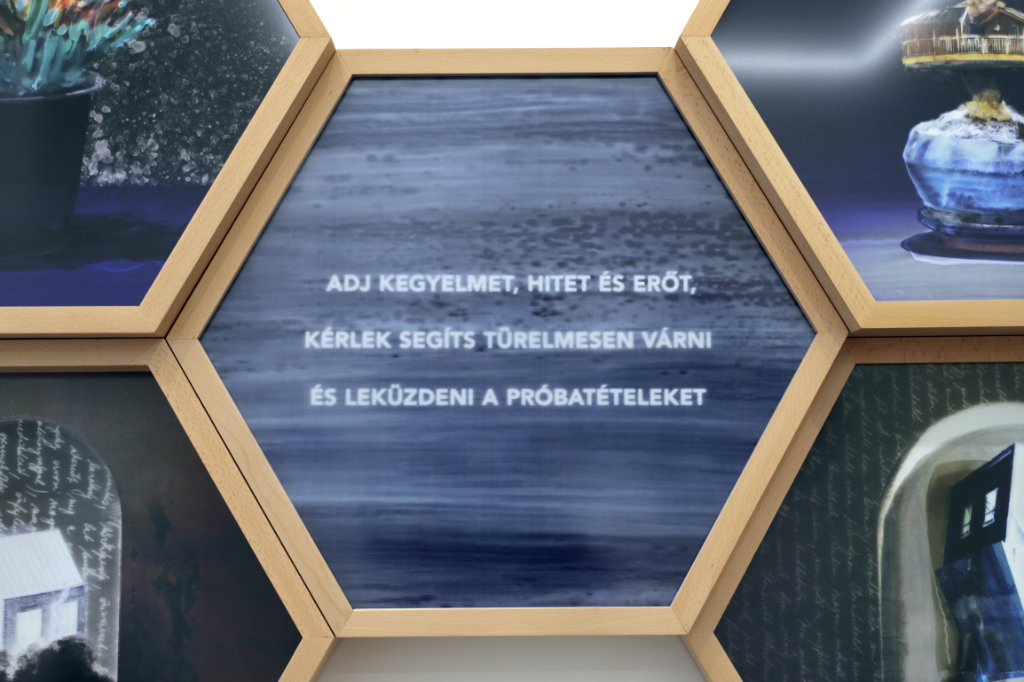

This installation combines twenty hexagonal frameworks on the wall with other photos, translating into a hive as a honeycomb structure that directly suggests a connection of experience, a like-mindedness and layers of interpretation about underlying societal expectations to follow through with production and reproduction.

I reflect on her work and her words; her response hits home. So much of my identity for the first half of my life has been wrapped up in the expectation of giving birth. In the past, I had ovarian cysts, which threatened the possibility of having children, and my boyfriend broke up with me because he decided on his own that the cysts meant I could not conceive, although my doctor had told me that I could still have children.

In the end, I have reached menopause without following through with having children, whether by accident or intention. I struggled with what I was supposed to be without this role of mother in my life. I am inspired to look more into Mayer’s work and understand its source and connection for both this personal reason and societal expectation. I log in to the hive mind in an abstract way as I carefully observe her work at the gallery.

The images are constructed in an unusual manner; the artist paints on glass, scans, and prints the images; it reminds me of the different processes of printmaking or dark room photography, the layers of experience, the transparencies, the demands of a process and its repetition, like the process of menstruation and its renewal, for some of us quite painful and debilitating each month.

Mayer talks about this background to the work; endometriosis and infertility are taboo in every field. Many people are interested in the topics of my exhibitions (Terra Incognita (2021), The Cradles (2018), more because they are very lifelike, with deep feelings. It gives hope simultaneously and communicates the raw reality of the expected child blessing. It draws attention to the problems and hopes of infertile couples.

I want to create a bridge with my work between families with children and childless families to develop an understanding and start a tolerant dialogue. For a year, I asked ladies with children, pregnant women or women expecting a child in an anonymous questionnaire how they should pray/have they prayed for the birth of their future child?

In her installation, the photos in the hives become shrines, both for hope and loss. The images of bonsai trees suggest a miniature world that we observe and capitulate to; tiny treehouses within each bonsai are as universes in themselves, a feeling envelops the observer of what I can only describe as saudade, this longing for a life that one wished for or that is lost in the past.

Mayer continues her explanation of her research and its focus, Nevertheless with my current works for a few years now I would like to attract attention to women with endometriosis and the problems associated with their disease. There’s not only the pain embittering their lives, but chronic illness often deprives them from the experience of motherhood. This can often lead to infertility due to the disease, statistically 50 per cent, which is a terribly high number.

Looking at each hexagon, I begin to see them each as shrines, mortuary shrines; I imagine the soul of a child in the bottles in some of her images, which contain written messages. I remember how my mother talked about her four miscarriages, how she felt about the babies that did not survive and how the fact that society forced her to ‘bottle up’ her feelings enshrined her in a perpetual state of anguish for their souls since they were not blessed and buried in hallowed ground.

Even today, women still keep this pain and heartbreak inside, there is so little opportunity or organisations that allow or aid in the grieving process, whether it be for a lost child or a child that was never conceived; this grief is the hope turned to pain for what never was or was lost.

Mayer touches upon this in relation to organisations in Hungary, The “Együtt Könnyebb” Női Egészségért Alapítvány (Foundation for Women’s Health) is the only official non-governmental organisation in Hungary dedicated to supporting women with endometriosis. They work with doctors, health professionals, institutions, organisations and experts in alternative therapies to help women with endometriosis. Patient information and community-based support are very important ideas.

Mayer incorporates some of the texts she collected from different women, their comments and hopes, and prayers in her works. These are also within honeycombs, another aspect of the collective hive mind. She explains more about the relationship between infertility and endometriosis in society. Talking about infertility is taboo. Those who don’t have children are often stigmatised, and people don’t even think about what might be in the background. Plenty of tactless questions hurt and burn into a person’s consciousness.

I look to the translation of one of the hexagons, “please help [me] to overcome this ordeal by providing strength, faith, and [your] grace” (adj kegyelmet, hitet és erőt, kérlek segíts türelmesen várni és leküzdeni a próbatételeket). It is a plea to some higher power, a desperate desire for solace, solidarity, and freedom from silence.

Some of Mayer’s images include bell jars or terrariums. Within these photos, the house might be overturned, a dramatic example of the shipwrecked feeling of a couple or potential mother who learns of her infertility or loss of a child; a house is literally capsized.

Another hexagon is an anxious plea to the unborn child, perhaps not yet conceived, “come boldly, you were born in our hearts, don’t sit there on the edge of the clouds, don’t wait any longer, because we’ve been waiting for you down here for a long time,”(gyere bátran szívünkben megszülettél, ne ülj, ott, a felhők szélén, ne várj tovább, mert mi itt lenn régóta várunk már rád).

Mayer talks about the radical difference between our exterior and interior selves and how we present our face to society, emphasising the need for support and the possibilities of finding it online, We always show the beautiful outwards, but in the meantime, we are often lonely. Retention communities no longer exist or are barely functioning. Although sharing experience could solve problems much more easily. On online social platforms, communities of smaller groups help each other anonymously, even with infertility problems and issues related to reproductive procedures.

I wondered how Mayer saw her work and if she considered it a form of social practice art or what connections she makes for herself when reflecting upon it. Her comments are revelatory. For years, my works have been devoted to current social and sociological problems, which can be traced back to my life experiences and questions.

I often touch upon taboo topics, such as illness, minority conflicts, problems of prejudice, migration, themes of death, coping with grief and questions of faith and religion. I am occupied with the relationship between the individual and society, the essence of Central European identity. Beyond personal themes, I strive to imbue my message with universal applicability by engaging collective consciousness.

This idea of universal applicability and collective consciousness resonated with my own work and social art practice. I was curious as to how she would frame this process visually. By trying to recast graphic design into ‘spatial graphics,’ my graphic art installations are often an intrinsic part of the space. They are frequently designed for sacral spaces, where, being an unusual pairing, the mundane and the sacral work well in juxtaposition. The installations are often accompanied by sound and moving imagery, she explains.

Specifically, in her exhibition, Terra Incognita, she has framed these prayers of anticipation, couples and mothers, waiting for a child, hoping for this sacred blessing. She includes texts shared with her anonymously through the questionnaires she circulates, which also become graphic elements in the hive. Mayer clarified I don’t know many respondents personally, but they were incredibly open, sharing their innermost feelings with me.

According to their feedback, it was a good experience for them to be able to write down what had happened to them. As they said, my questionnaire is not statistically but rather psychologically based, with a series of questions focusing on personal stories.

In terms of some of the questions she has asked, Mayer makes a poignant comment about feelings of guilt. She dives into the details here. For example, I was interested in if they felt guilty for doing something wrong in life or if they didn’t live properly for not having a child; what or who gave them the strength to make their lives meaningful again after the trauma? What helped reconcile? Did they reinterpret their lives, did their faith change? And the ladies replied willingly and very honestly, Despair, hopelessness, pain, immeasurable frustration, helplessness, loneliness, isolation, sadness, anger, anxiety, panic.

Another example of a response to her questions is at the core of self-worth and identity; Mayer quotes one of the women who responded to her questionnaire, I didn’t see the future; I couldn’t imagine it without a child. Then I told my husband to look for someone else to give him a baby. He has stayed with me, and we are happy parents today. Some have reported that this has not broken their faith either: ‘I have always been a believer. Really the process of mourning strengthened my faith. It has been unbroken ever since; there is something to hold on to.

There is a history of personal mythology in Central European art, which creates a foundation for the process of collective and personal experiences, which Mayer refers to. She cites her thought process, “I relied on lived experiences, so I tried to incorporate the occurrence of personal mythology into smaller systems in connection with living a successful and unsuccessful expectation of a baby.

Mayer has brought together these images, prayers, and personal responses from others as icons of shared history. These bottles contain feelings and souls; these bonsais with tiny treehouses are worlds within; these hives are a part of a whole, a shared collective storytelling, our stories, everyone’s stories.

She concludes the lessons she has learned, the inner wisdom of the collective mind, That you shouldn’t give up. Hope, patience. At the end of the series of questions, I wondered if their lives had taken a more elevated, perhaps more spiritual direction since then.

Was the trauma interpreted from a broader perspective? What have they been doing differently since then? I received feedback from almost everyone that, they strengthened spiritually, their relationship with their family became closer, and their friendships cleared up. After these kinds of difficulties, only the true things remain. T

hese women, for example, have great respect for their husbands for staying with them; interestingly, only one or two cases ended in divorce. They have become more patient, many have moved to more stress-free workplaces, they have started to deal with themselves on a spiritual level, and they now lead a much more conscious and healthy lifestyle.