Words by Pietro Consolandi

Before the explosion

If a genie from the future had visited Venice just a few weeks ago, showing images of an empty Piazza San Marco or Rialto, or the perfectly still water in the Canal Grande and its natural yet unusual transparency, we would have immediately thought about a movie or a hoax. And yet, it didn’t take long for the streets to empty, the water to clear up, and the air to freshen. Those days were when Italian social media were full of people sharing memes about Chinese bat soup and joking about Covid-19, feeling safe from our first-world position, thousands of km away from those images of people locked up in an extremely disciplined quarantine. Unconsciously the thought was: it would be impossible to lock Italians up like that, with our famously chaotic lifestyle, but it’s also impossible that such a disaster would hit us; we’re not China, after all. Of course, the events proved us wrong in our chauvinist illusion.

The first methods Italy implied to fight the virus, even before the first infections were registered near Lodi and Padova, were those our right-wing often invokes against other kinds of “alien menaces”: close the borders, cut them out, protect our economy. Flights between Italy and China were cut unilaterally, not even communicating with Chinese authorities or coordinating flight plans with the rest of the world, causing mayhem in connecting flights, the impossibility of checking paths and implementing proper sanitary screenings.

As philosopher Byung-Chul Han noted on El País [1] last month, this sort of reaction is well rooted in the European tradition of sovereignty: a response as instinctive as anachronistic, a collective mania to control. He who is sovereign decides when and where to raise frontiers when the emergency begins. Such an old-fashioned display of autarchy was counterproductive, as such threats do not care about uncoordinated border controls – they don’t seem to care much about borders at all. Malpensa airport was still much easier to reach from Wuhan than any remote rural area of China, and this is because the very means created by the free market in order to circulate wealth at the fastest pace possible, were exploited by the virus, mimicking the movements of globalized financial capital.

At the early stages of the Italian pandemic, a public letter to an international journal [2] by 13 medics of Bergamo’s main hospital, epicenter of the worst outbreak in Italy, underlined how a lack of coordination within the health system, caused mostly by the increasing transfer of decisional power to regional and local institutions, worsened the situation. Each hospital thought for itself, morphing into virus outbreaks that then spread into Lombardia rather than being safe bastions against the infection. Instead of seeking help and isolating the virus, hospitals were led by the system’s bureaucracy to act individually. Each one has to fix its own problems for the sake of cost efficiency. This shortsighted customer-oriented care model, point to the need for long-term “community-centered care”.

Another key structure which led to the Bergamo outbreak was the rich industrial texture surrounding the city. Since the beginning of the emergency, companies have insisted on keeping open and productive, forcing their workers to be exposed to the infection through the heavy influence their union – Confindustria – has on the government. In fact, the union even rushed to their communication channels to reassure their global partners and customers with a video message: do not worry, we will keep working as always. Too bad that the workers did not have similar reassuring messages but rather were forced to keep working, often with insufficient safety measures. Otherwise, the company would have been overtaken by the competition.

All these elements are consequent to the political agenda Italy followed with our North-Atlantic block. It made the virus deflagration devastating, with effects that will stretch for many more months worldwide. The spectacularly blind reactions to the virus displayed by right-wingers such as Trump and Bolsonaro – to quote the loudest ones – follow their irresponsibly selfish way of seeing the world and will translate into extremely painful sacrifices. Moreover, intuitively, pointing at the scapegoat WHO as a Chinese conspiring agency and unilaterally cutting funding will result in more isolation and less coordination, leading to even more international health risks.

Climate change has also been associated with the A-bombings in Japan: a sudden and unexpected explosion which unfolds its nefastous powers far beyond the borders of its blast and on a totally different time scale. Trying to understand Hiroshima’s trauma, Kenzaburo Oe tells us the story of philosopher Moritaki Ichiro who, at the moment of the explosion, noted the previous day’s memories on his diary: August 5, 1945. A beautiful sunrise. Made 500 bamboo spears [3].

The Japanese people were preparing to resist the US invasion, fueled by their government’s refusal of any peace treaty, arming each citizen with a bamboo spear. The blast in Hiroshima incinerated any resistance, physical and moral. Moritaki could only see a glimpse of the explosion and lost his sight in one eye. The nationalistic response Italy had against the virus was similar to those spears: a precaution which acted on a wholly different level from that of the threat, uncoordinated and which comforted its people with false hope of safety.

A few years into the end of the world

Curiously, many of the arguments adopted worldwide for not cutting emissions follow the same flaws that pushed Italy towards disaster. Led by their industrial and financial elites, States hang on to their right to extract and consume: emerging countries argue that developed ones built their wealth on decades of unregulated emissions, so they have the right to do the same; at the same time, developed ones fear being overtaken if they cut their emissions, bringing the world day by day further into climate apocalypse. This is perhaps why the environmentalist call to “act now before it is too late” is ridiculed by denialists since the latest projections about sea level rise show a 2050 scenario almost three times more catastrophic than previous ones. They won the battle and are right: we’re already inhabiting the end of the world. Yet, this does not mean that we should keep going at full speed into it.

An alternative approach to the early stages of the pandemic from that of meme-sharing racists quoted above is that of quite a few ecologists who, perhaps rightfully, were stressing the different perceptions between the incoming health emergency and the ongoing climate crisis, more or less ignored by our species. This point has to be made, but the “my emergency is more urgent than yours” way of arguing is rather ineffective. This communication flaw has been further aggravated by another rhetorical strategy upholding the virus as our saviour, sent by divine providence to rescue the world from humans. Some humans are bad, but the complete extermination of our species is perhaps not the best solution.

Such spectacular declarations are simplistic and counterproductive as they fail to consider the global emergency acting in a network relation with both catastrophes: the surprisingly fragile structure on which we rely. The globalised economy has been steadily eroding any safety net for the global poor, especially for populations in geographically unlucky areas of the world. Through what Naomi Klein has defined as the “shock doctrine”[4], disasters were consistently exploited to erode welfare systems and public sectors, facilitating venture capitalists’ attempts to suck up profits and pointing to the promise of fast consumable profit as the way out of trouble for everyone. This made it hard for the Italian sanitary system to organize itself, satisfying the demand for medical masks, but also made it impossible to cut emissions and take real measures against climate change for decades. After all, we have a global consensus in this sense since the 1988 Toronto Climate Conference [5].

The difference in global perception is anyway striking. The virus seems to have persuaded vast parts of the population to agree on something that should be basic for any living entity: life itself might be more valuable than production.

The climate emergency is far more sneaky than the virus as it does not act in such a spectacular and coordinated fashion. The virus poses a direct threat to Wuhan, Milan, Madrid and New York more or less at the same time and for several months in a row, whereas floods, droughts and other phenomena strike locally and then disappear for a while, allowing who profits from such shocks to convince us that, in the end, we can fix that. Venice and Jakarta might sink, but we can relocate them; a few Pacific Islands will be swallowed by the Ocean, but there are a whole lot of other islands; large portions of Australia, California, and the Amazon rainforest might burn, but that has always happened and it’s just slightly worse, we will fix it.

This kind of rhetoric seems to point out that we are exploiting nature too much, but that’s for a supposed greater good. The whole is more than the sum of its parts, as common knowledge goes, so one must thank for what we have despite drawbacks and collateral damages. Except that is not true: as Tim Morton argues, the whole is actually less than the sum of its parts. It just looks much bigger [6].

When applied to everything, this holistic approach justifies sacrifices that do not have to be made necessarily. Each entity participates in many “wholes” and has an incredible amount of peculiarities which escape the grasp of such aggregations, so no: the Covid, the cruise industry, and neoliberalism itself are not so big after all. What does it say about the “whole” named humanity if we allow Venice or Jakarta, entire archipelagos and rainforests, populations and cultures to disappear because we can’t bring ourselves to question another – actually much smaller – entity?

Venice as a symbol

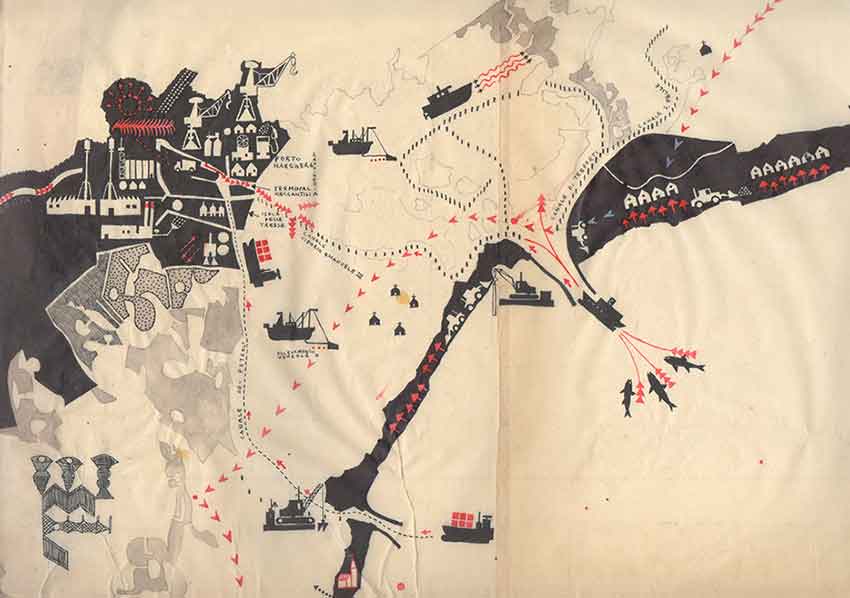

The lagoon of Venice, an extremely fragile ecosystem, is enduring the devastating effects of man-made changes to the environment and uncontrolled tourism. Its fragility and success are intrinsic to the way the city was built. Its lagoon was at once a rich ecosystem and a natural defence, granting its people a privileged spot in the Mediterranean Sea.

Due to its enchanting historical beauty, Venice has always attracted visitors and plays a major role in modern tourism. But is this really an advantage? Perhaps some tour operators would say so – they’re right, it is an advantage for them – but for more than 50.000 people still refusing to leave it, thousands of students who would like to stay and a vast crowd of affectionate and responsible visitors who come back several times through their lifespan, it is not quite so.

The fight against an irresponsible form of tourism management and the disastrous ecological governance of the lagoon famously found its most visible, arrogant and paradoxical enemy in the Moloch-like cruise ships crossing the Canale della Giudecca and overshadowing the city’s bell towers, each with thousands waving passengers. Only Carnival corporation’s ships in Europe emit 10 times more SOX than all of the old continent’s cars, hitting Venice worse than any other city besides Barcelona and Palma.

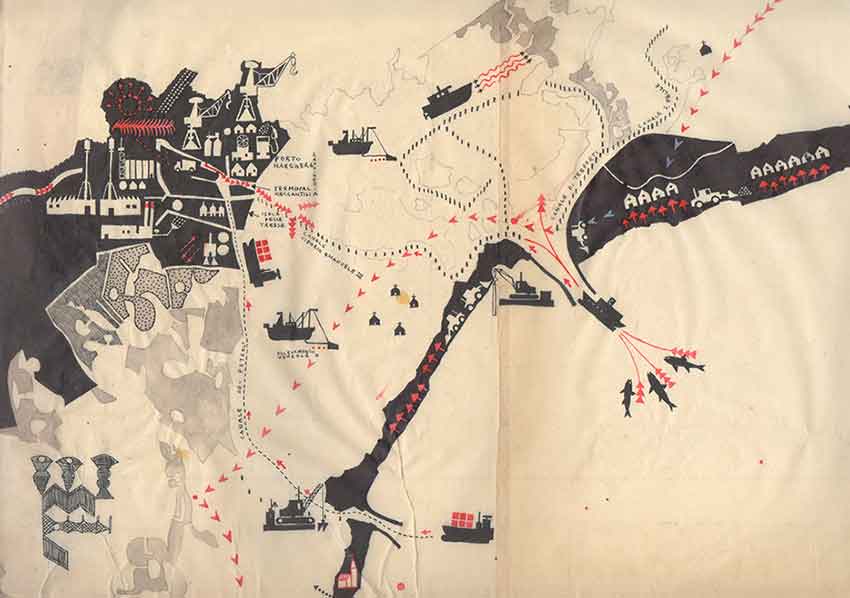

Cruise companies commercially penetrate the cities they offer to their passengers, shaping them accordingly to the easy and consumable image they want to sell, as artist and activist Eleonora Sovrani underlines in her work. Meanwhile, ships are growing larger and larger, carrying now more than 6000 passengers. Costa even made a Venice-themed vessel – a grotesque monument in spite of Venetian demonstrators.

Venetians hear a lot of questions about their town and the eternal it must be so strange to live there; how is it? is now being reached by questions such as Oh wow, I heard about the flood, is it alright now? and “I saw a photo of that huge ship next to St. Mark… How can you allow that?”. Venice has a unique symbolic power and is increasingly becoming a warning for mankind about the collateral damages of irresponsible developments. Many superficial gazes dismiss it as a city that cannot enter modernity, doomed to disappear as all things belonging to the past, but the more we venture into the future we’re shaping, the more we see something different: Venice is anachronistic, yes, but not as a theme park where we roleplayed life in the XVII century; it’s rather the opposite, it anticipates the future.

This is also why Venice took the international stage as the queen of the media – and fake news – worldwide during the virus infection. Numbers here are not nearly as high as in Bergamo, Madrid or New York. Still, it allows us to see something different from the devastation caused by the pandemic: Venice without the lens of exploitation and mass touristification. left to its slow rhythm, no one rushing to take a selfie that will capture the very idea of this town before leaving for the next destination. There are still people there: they live in isolation but will remain there once the virus leaves.

Venetians fought the cruise industry for several years with several marches and protests leading to last year’s No Grandi Navi demonstration in St. Mark’s Square, usually crowded with tourists rather than locals. Yet, nothing had changed before the virus hit, highlighting many of its already existent problems relating to impunity and a spectacular lack of care towards the health of ecosystems, passengers and crew members.

The first and more prominent case of Covid-on-board, as reconstructed by Rowan Moore in his deep analysis of the cruise industry’s critical moment [7], was that of the Diamond Princess on the coast of Japan. After that, several ships were denied access to ports throughout the world, including Venice: now that the virus threatens us, they can’t enter. Earlier, when the only threats were to houses’ foundations, the quality of air and the Lagoon’s ecosystem, they were alright.

The last cruise ship at sea, luckily with no Covid cases, was the Costa Deliziosa. The same ship nearly crushed a yacht harboured outside the Biennale while leaving Venice in the midst of a storm last July and was the first to depart from Venice on the very first days of 2020, planning to return on the 26th of April after a tour around the world. After the global crisis exploded, passengers have been cruising hostages for over a month until an agreement was reached with Barcelona and Genova in late April. In the meantime, workers on another Costa’s vessel are also struggling after roughly a quarter of the 623 crew members were infected while harboured in Nagasaki.

Venice is now closed to cruise ships, but those most suffering for it are still the passengers and crew, a reminder that the ticket or contract conditions do not include the right to a safe ride, clean air or personal space. Just as it does not guarantee the respect of the environment, as several events like those leading to the 40 million fine to Princess Cruises prove, such fines, of course, cannot undo the environmental damages deliberately caused, as they only take out a share of Carnival’s 3 billion yearly profit, and arguably won’t – if no action is taken – deviate the upcoming cruise investments in the extremely fragile ecosystems of the Arctic and Antarctica. Paying the fine and apologizing is an investment like any other.

The way out?

The absolute disregard and lack of care of the cruise industry towards the environment as well as the health and safety of its passengers and crew, highlighted by the Miami Herald, shows the paradox of a system upholding the fastest possible circulation of wealth as the central element of our existence: the current economic system indeed has the ability to create the superfluous – as some love to highlight – but since nothing is created. Nothing is destroyed. What about the collateral damages of such superfluous production?

Unregulated destructive businesses exploited the non-local quality of economics to sweep under the carpet the devastating side effects of their actions: impunity for the disasters and ecocides caused, covering the devastating effects on weaker economies and ecosystems, disregarding any form of life that does not bend to extractivist and productivist dogmas. This careless system focused on short-term wealth production has condemned our species to waste decades in our fight against climate change and facilitated the spread of the pandemic through very similar mechanisms.

These alarm signals are already shaking our consciousness, as noticeable in several governments’ responses worried about the health of their people. Some limitations to the free market are being raised despite industrial complaints, while at the same time, severe limitations to personal freedom are being implemented. Many thinkers, most notably Giorgio Agamben, are stressing this latter condition while ignoring the first, worried that the cyber-police state will take over permanently exploiting the pandemic shock. This approach is based on a legitimate mistrust of political authority. Still, it feels quite paranoid, and it’s shocking to see Agamben and USA gun activists on the same side of any social fight.

While some governments will implement tighter social control systems, we will unlikely live in a future of perpetual lockdown Foucaultian dystopia. The main reason for this assumption is obviously not ethical but rather economical: the capital is not profiting from this situation. And this is why, on the other hand, the environment is swiftly recovering.

The logical fallacy caused by fear is to create a false dichotomy between so-called “naked life” and Life in its fullness. To protect one is not to discredit the other: we are not only surviving for the sake of it, but because we desire to live on, and possibly be able to erase past mistakes. In his illuminating essay Biopolitics of Catastrophe[8], Fréderic Neyrat points to the necessity for repressive biopolitics to turn into creative “ecopolitics”: not just preserving βιος (life) but to take care of our οἶκος (house). Our current political system adopts a just-in-time type of government based on risk calculation in order to preserve the current status quo and acting just before the catastrophe, eventually failing or trying to direct catastrophes to less privileged areas or layers of population rather than transforming itself. In other words, this means relieving the catastrophes while maintaining its causes intact.

The way out of this catastrophe we’re enduring seems thus fairly utopian but simple: this time, we should reverse the shock doctrine; through awareness, collaboration and grassroots political action filling the void left by institutional powers. This shock must not be exploited once more by the same powers that made a profit on previous ones; it has to be a call for transnational collaboration against the many emergencies we’re facing. We cannot fight the health emergency without tackling the environmental and social ones.

It is essential for theorists not to collapse into paranoid fear nor to mistake the virus as a messiah who came to lead us into a brighter future: attempts will be made to profit from the Corona shock, led on many fronts by corporations, governments and think tanks equally. Today, naturally, we all crave to go back to our lives as they were. We focus on what we lost, much like grief: we miss the fresh air, the sun’s warmth, and the happiness of being together. This is the most dangerous trap: we can’t wait to return to normal life. This natural feeling that is making philosophers shake in their bones for human warmth is correct, but we must wait for life to restart in due time, as we must wait for the economy to slow down. Because in the end, Italian kids drawing their “andrà tutto bene” (everything will be alright) might be right or wrong just as philosophers thinking “sarà tutto terribile” (everything will be dreadful).

We can’t really use the future tense with such certainty, but we can remember that life before Covid-19 was not as good as it is in our minds. I can’t see what Agamben, also a Venetian, wants to return to so eagerly and hastily. I also miss terribly many things. I’m also craving to get back outside, sharing life with other fellow humans. Still, I’d rather do so without the smoke of a cruise ship intoxicating us and its dreadful silhouette covering the sunset. Perhaps that is not as impossible as it seemed just a few weeks ago.