Text by Katažyna Jankovska

Fragmented phenomena and knowledge seem to be structuring forces within our society. We are surrounded by ever-emerging incomplete narratives that reveal new connections and subvert established, seemingly complete stories and continuity. Fragments point to something unstable, fluid, and transitory.

The theme of this year’s FIBER Festival in Amsterdam is exploring exactly this – heterogeneous fragments, and slices of the world, acknowledging both inherent incompleteness and their restorative potential. Four days of the festival featured performances, talks, and an exhibition strongly emphasising listening practices and world-building, pluralizing voices, and weaving together bits and pieces of deconstructed and reconstructed narratives.

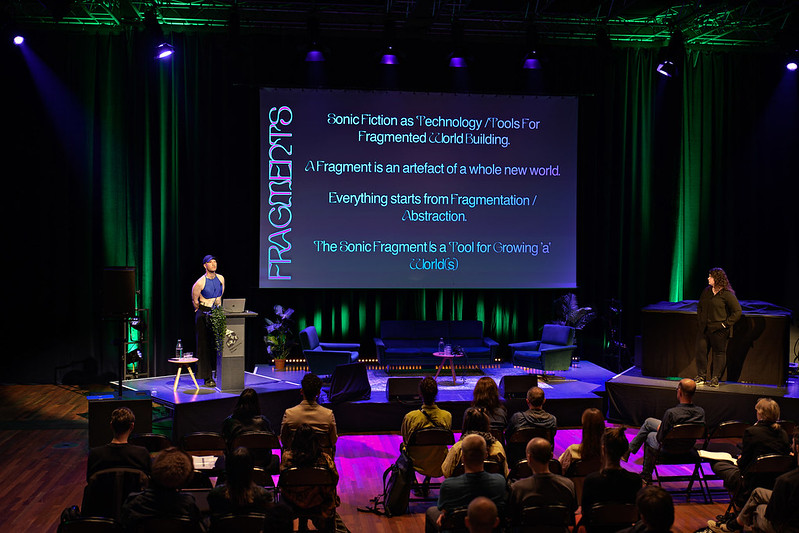

As Frey states, defining a fragment is a nearly impossible task – giving it contours or considering it as a separate whole contradicts its fragmentariness. The fragment is a dynamic process, always in motion, blurring together different temporalities. But what does it mean to think of sound as fragmented?

Noel Lobley suggests that sound can be seen as a part of something being broken, detached for examination, analysis, preservation, and consumption. It can also be an intransitive fragment – one that has no direct object, where something falls to pieces, the sound that is fragmented, collapsing under the weight of forces acting upon it. It can be transitive, the sound that has a direct object and breaks something up or causes it to disintegrate into fragments. These characteristics define sound as inherently incomplete, unstable, fluid, and ever-shifting.

Technological advancements in sensory extensions are significantly filling gaps in our fragmented sonic knowledge, expanding our auditory focus beyond the usual range. Next to the traditional audio recording devices, nowadays, listening and recording technologies are placed in nearly all the ecosystems of the world, from aquatic to celestial environments, creating a network of technological ears stretching across the planet and collecting sonic pieces of the work that lie outside of our natural perceptual range.

However, the lack of access to certain realms is not the sole reason we cannot hear. Take, for example, the famous recording of the humpback whale song in 1970. In fact, when there are enough whales in the water, humans are able to hear those subaquatic sounds. Yet until the famous recordings were done, no one heard a sound. As Blackfoot researcher Leroy Little Bear says, The human brain is like a station on the radio dial; parked in one spot, it is deaf to all the other stations… the animals, rocks, trees, simultaneously broadcasting across the whole spectrum of sentience.

Human hearing is based on selective auditory attention. As the festival symposium speaker Sean Cubitt noted, Hearing has been a selective practice for a long, long time. We teach our children to prioritize certain sounds – the mother’s voice, for example – over the background ambience. What breaks down in modernity, and is accelerating now, is the hierarchy of sounds. This is where we differ from our technological ears – they do not exclude sounds; they hear everything while we constantly filter out sounds, making decisions on what to listen to, whether consciously or not.

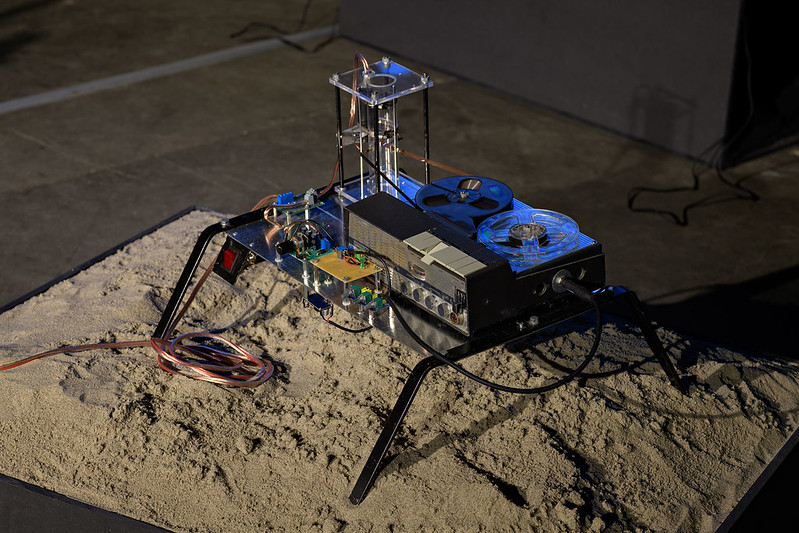

The FIBER Festival exhibition around the same theme presents diverse listening opportunities with recordings from different sources. By extending our ears with technology, artists put forward fragmented sonic slices of the world, crafting a new soundtrack of the planet.

Jan Christian Schulz creates listening extensions in the form of an inflatable body equipped with piezo-electric vibration sensors and microphones. His Prosthetic Sensorium can exist in distant environments, which humans sometimes could not physically reach, capturing sounds from ponds with cracking frogs, shimmering trees, noisy streets, and far away deserts. Similarly to underwater, which was thought to be silent for a long time, we are now discovering that soil is, for a matter of fact, a very noisy place.

Christine Hvidt explores soils that are dense with vibrations and sounds produced by plants, worms, and other microorganisms. Her sound installation Edaphon, consisting of ceramic coil sculptures put on the formed soil ground, tries to amplify the dynamic nature of the soil, capturing the constant movement of diverse organisms living underground, revealing previously unnoticed soundscapes.

Exploring even more inaccessible realms, Myles Merckel’s sensing instrument identifies, records, and amplifies airborne organic particles (dust, pollen, soot, and aerosols) invisible to the eye, floating around. The Lights Which Can Be Heard by Sebastien Robert presents the sounds of the aurora borealis. His research stems from the theories of various indigenous communities living in the Arctic witnessing the sound, the natural, very low-frequency radio waves produced by the Northern Lights. The installation allows visitors to hear the aurora sounds through the crystal found in the Arctic by preserving them into the light.

As Nicola di Croce suggests, disturbing sounds, such as the cracking of icebergs or glaciers, have the potential to disrupt the status quo and introduce new politics of existence. The definition of disturbing sound has been shaped from a human-centred perspective; thus, attuning to such sounds may shake power hierarchies and make us rethink our sonic environments. Similarly to disturbing sounds, fragmentation can potentially disrupt conventional structures.

This became even more visible with the invention of technologies like film and photography, segmenting reality into a series of frames and using the techniques of montage and collage to unify different narratives through fragmentation. The principle of construction and deconstruction corresponds with the perception of reality being fragmented, offering the ability to reconstruct the pieces into new wholes and subvert existing narratives.

While we are becoming aware of previously unreachable worlds and trying to attune to nonhuman sounds, what new paths and realities can we construct and imagine? Another common theme at this year’s FIBER Festival is the focus on artistic practices that engage in world-building, decentralizing the human and allowing fragmented narratives to grow into novel forms. Reassembling dispersed pieces into new narratives results in entangled temporalities and nonlinear, fluid processes of meaning-making.

One such example is the artistic practice of the artist Jordan Edge, who creates fictional sonic environments centred around the voices of animals and artificial entities. During the symposium, the artist shared insights about their use of AI-generated narratives to create trans-species sonic fiction, consisting of sonic languages that exist beyond human perception.

Studio Above&Below discussed their work Meditative Cohabitation, a speculative project about the future Brussels ecosystem, looking into bioacoustics and translating nonhuman communicative signals into immersive audio-visual work.

Next to that, FIBER presented a range of audiovisual performances, such as Spekki Webu & Matti Vilho’s live AV show Signal Transmutations that took us on a journey through different stages of life, exploring the cycles of birth, death, and rebirth by layering temporalities and incorporating nonhuman elements.

Nonhuman elements occupy a central role in the world created by Tianzhuo Chen, who merges fragments of the past in the three-channel video work Dust, exploring rituals and ceremonies in the absence of humans. Separating ceremonial objects from their users, the artist places the landscape around Cuogao Village and Damu Temple in the Nagqu District of Tibet as the work’s primary protagonists, filling the narrative with human traces and fragmented symbolism.

Josèfa Ntjam’s film Dislocation follows a fictional character Persona on a journey from the internet(s) to a cave floating into outer space. Colliding stories and memories from her ancestors’ fight for Cameroon’s independence, Persona gradually transforms and loses her gender. The artist composes fiction by blurring temporalities, raising questions about the possibility and importance of perpetual reconfiguration.

What futures can we create from a fragmentary starting point? The FIBER festival shows that fragmentation is not necessarily a limitation but an opportunity for transformation and imagining alternative scenarios. By decentralizing the human perspective and embracing fragmented narratives, the festival fosters the plurality of voices and experiences in our sonic environments, forging new pathways beyond our human perception of sound and inherently selective hearing.