Text by Robert Barry

In 1965, a man sat on a chair with electrodes strapped to his head and performed a piece of music using just the power of his mind. Nearly six decades later, that work is being revived, albeit with one crucial difference: the man is no longer there, replaced by a small cluster of cells in a mobile laboratory.

Alvin Lucier was always rather a cerebral composer. His music could take far-out concepts and transform them into dazzling sensory results. Composed in 1969, his I Am Sitting in a Room consisted simply of a short text, opening with the eponymous line, spoken by a solo performer, then recorded and played back into the room again and again, with each iteration then recorded and played back with the additional sounds of the playback environment until the ambient room tone finally engulfs the sense of the words. The results are strangely mesmerising, with the ultimate sonic outcome a kind of woolly monotone whose pitch will be different each time, depending on the acoustic signature of the space itself.

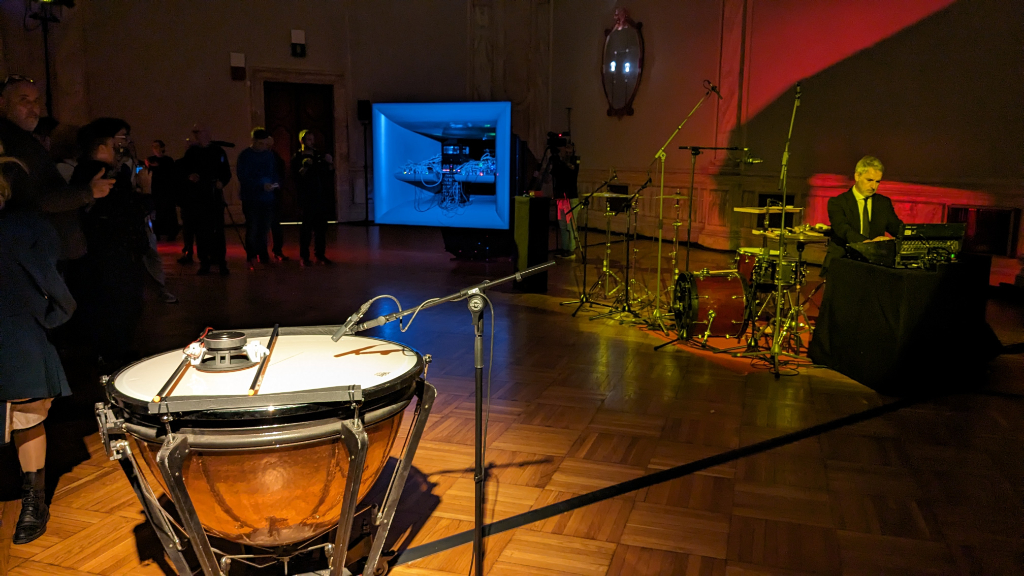

Music for Solo Performer is perhaps even more beguiling, composed just four years earlier. First performed at Brandeis University’s Rose Art Museum in Waltham, Massachusetts, the work saw Lucier himself sat with wires trailing from a headband strapped around his temples to a panoply of amplifiers and loudspeakers. Between the electroencephalographic sensors on the composer’s forehead and the speakers down the line stood a filter intended to cut off the signals from all brainwave activity outside the range of about 8–12 Hz, leaving just the so-called ‘alpha rhythm’ believed to occur when the mind is at rest, as in certain meditative practices. Lucier closed his eyes, cleared his thoughts, and as the wires sent those ultra-low frequency signals below the threshold of human hearing to the speakers, a battery of percussion instruments placed around and on top of them started to vibrate.

In concert, it can be a pretty slow-burn piece. At early performances in the ’60s and ’70s, critics would often brag they hadn’t stayed the course to the end. But there’s an undeniable sense of theatre to it from the assistant’s careful application of the electrodes to the performer’s careful closing of their eyes and the sometimes quite long gap of silence before the final – seemingly miraculous – activation of the various drums and gongs spread about the space. What would happen to that were you to simply remove the central star performer?

Lucier himself died in December 2021. But in his final years, he entered into a conversation with two artists that would lead to a remarkable new version of the piece, performed at this year’s Biennale Musica in Venice. Nathan Thompson and Guy Ben-Ary first made contact with Lucier back in 2018. At the time, they were working on another project called CellF. There have been numerous attempts to compose music using computational artificial intelligence since Illinois professor Lejaren Hiller’s pioneering (1957) string quartet, Illiac Suite. CellF is different. It is a modular synthesiser controlled by a biological neural network.

It started ten years ago, Ben-Ary explained to me over Zoom one afternoon recently. We grew neural networks outside of the body on a specialised interface and then we interfaced them to modular synthesisers. From the beginning, CellF was always a collaborative project. Ben-Ary and Thompson were interested in watching this synthesiser controlled from a petri dish of barely animate cells and seeing how it evolved, learned – and played with others. Since its inception, numerous musicians have now jammed along with CellF’s neural network. But one artist that Ben-Ary and Thompson had always wanted to get involved was Alvin Lucier. Alvin was a great inspiration for us, Ben-Ary told me. The whole idea of using cognitive processes to control what you compose was always the basis of this project. That basis he attributes to the inspiration of Music for Solo Performer.

Unfortunately, something kept getting in the way of this dream being realised. We were fortunate enough to set up a gig in 2018 to play with CellF and Alvin Lucier, but unfortunately, he fell and broke his back, and this show was cancelled, Ben-Ary explained. It was all locked in, he continued. The idea there was to get him to wear the original headset from 1965 and to use it to stimulate the neurons that we had on this interface.

After he got better, we tried another time, in September 2020, at the New School in New York City. And that got cancelled as well because of the damn coronavirus. Twice we were booked to meet him and play with him, and twice it got cancelled.

Meanwhile, however, they got to talking. Right from the start, Ben-Ary told me, Alvin was fascinated by the project. He could actually see how it extends his intention from 1965 in ways that back then you couldn’t anticipate because the technology wasn’t available and the knowledge wasn’t there. As their plans to have Lucier perform with the CellF synthesiser were continually reported, the three artists started to hatch an even more radical plan for collaboration: the idea, as Ben-Ary put it to me, of getting Alvin to keep on composing and keep on telling stories or making art in a museum into the future continuously and after his death.

Many artists had lockdown projects. Many people who aren’t artists temporarily became artists simply in order to have something to do during lockdown. As the reviews editor for an independent music and arts website, I’ve been sent all sorts of stuff—tons of things. But no-one else, to the best of my knowledge, made it their lockdown project to collect a blood sample from an elderly avant-garde composer, barely a year before his death, before using a technique known as ‘pluripotent stem cell technology’ to manipulate those blood cells into producing a network of new neurons.

But that’s exactly what Ben-Ary and Thompson did. In effect, creating a basic model of the brain grown organically from Lucier’s own organic material. A kind of neurological clone. The second brain of Alvin Lucier.

There are long-term plans to integrate this Lucier mini-brain into a permanent installation. It’s all part of a project called Revivification that Thompson and Ben-Ary initiated with (the real) Lucier while he was still alive and now see as their mission to commemorate the memory of our conversations with him. In the meantime, Music for Surrogate Performer, Thompson and Ben-Ary’s project for Venice re-stages Lucier’s original Music for Solo Performer albeit it with the neural network standing in where the solo performer once was. The work is a speculation about the future,” Ben-Ary told me, “taking the historical piece and closing some sort of a circle.

It’s enormously poetic, this idea, that this neural network has grown from stem cells that were grown from Alvin Lucier’s own blood and now they are in some sense controlling a performance of his own historical work. But just imagine, I asked the two artists, if somehow there had been some kind of mix-up at the laboratory and Alvin Lucier’s blood had got lost and been mixed up with some other guy’s blood and then that blood ended up producing the stem cells from which this neural network was grown, would that actually have made any difference? Would it change the musical result?

There’s a pause. For a moment, I can hear the wind whistling through the fibre-optic cables. And then Thompson says, We don’t know.