Text by Clara Muller

Fifty years ago, on July 20, 1969, the Apollo XI mission successfully landed on the Moon. Half a billion Earthlings anxiously watched as American astronauts took their first steps among the stars. Most people were probably wondering how it felt like to be up there, but maybe a few even wondered how it would smell like out of that glistening, air-tight helmet. And if no one thought of it at the time, people are certainly curious about it now.

What does space smell like? Such an internet search prompts thousands of answers. In the almost complete vacuum of space, of course, no breathing or smelling is actually permitted. But astronauts have reported that once brought back into the breathable atmosphere, some components react with the oxygen and moisture and do have a distinct aroma! They have described the smell that sticks to their suits after spacewalks as similar to ‘sweet-smelling welding fumes’ (Don Pettit), ‘spent gunpowder’ (Thomas Jones, Gene Cerman), seared steak and hot metal.

All of these descriptions share a definite smokiness that is suspected to come from the combustion of dying stars, which produces polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. But these are not the only smelly substances encountered in space, and several scientifically-curious artists have drawn inspiration from these various stenches to create a form of non-visual Space Art. Before being able to see the reality of the objects floating far from the human gaze, men had to put their imagination to good use [1].

Until the 17th century, representations of space were limited to what one could see with the naked eye – the sun, the moon and the stars – and to what the imagination, imbued with religious and metaphysical beliefs, made of it. For a long time, constellations, for instance, were depicted as fantastic beasts roaming the night sky. It was only in 1609, when Galileo perfected the telescope, that men discovered that the sky was filled with gigantic objects and strange new worlds lying beyond their reach. The shift of perception brought by this mediated vision was beyond measure. From then onwards, intertwining scientific observations and fantasies, astronomers, artists and writers started to imagine what these worlds could look like and how one could travel there.

As time passed, Space Art was increasingly influenced by discoveries in astrophysics and advanced optical technologies. In 1851, photographer John Adams Whipple, with the help of the Harvard Observatory, successfully captured a few decent views of the moon through a telescope2. Visions of the cosmos then continued to imbue the arts through various mediums. At the turn of the 20th century, one of the very first films, A Trip to the Moon (1902) by George Méliès, began Hollywood’s never-ending craze for science-fiction movies. And this fascination never wore off.

Contemporary artists still draw inspiration from the cosmos, in more or less scientific ways, and sometimes drifting away from the visual arts. Several artists have for instance created aural installations from sounds recorded in space, thus transforming Pythagora’s concept of the music of the spheres into an audible, artistic reality.

After two millennia of attempted representations and evocations, what was left for Space Art to conquer? What final frontier was left to cross? Although western culture has long denied the ability of smells to provoke aesthetic experiences, this idea has now been largely challenged by thinkers as well as artists who started to embrace scent as a legitimate medium. An art where volatile molecules have replaced pigments.

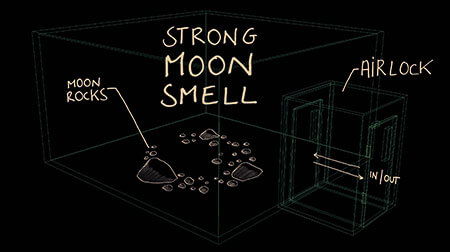

Right: Enter at Own Risk (preparatory drawing), WE COLONISED THE MOON (2011)

Artists Hagen Betzwieser and Sue Corke, together form the duo WE COLONISED THE MOON. Working in between art and science, imagination and reality, the duo has developed a series of works concerned with the smell of the Moon. According to astronaut Charlie Duke, Moondust smells like gunpowder and burnt charcoal.

Collaborating with scent chemist Steven Pearce, the artists re-created this extraterrestrial aroma and micro-encapsulated it on scratch and sniff postcards. In 1962, Yoko Ono had already envisioned this possibility in one of her instruction pieces – famously gathered in The Grapefruit Book (1964) – stating: ‘Send the smell of the moon.’ Progress in various sciences, from astronomy to chemistry, have finally allowed, almost half a century later, to carry out her vision.

Smells are strongly associated with memories. It has to do with the idiosyncratic way we learn and memorize them in our limbic system where olfactory information simultaneously goes through the amygdala, charging our experience with emotions, and the hippocampus, acting as a library of memories. With MOON, Scratch and Sniff (2010), WE COLONISED THE MOON offers a singular, imaginary memory, allowing you to keep and share an olfactory souvenir of a place you have only visited in dreams.

Betzwieser and Corke’s project took on yet another form a year later at Liverpool’s Foundation for Art and Creative Technology, with a performative and immersive work entitled Enter at Own Risk. Visitors entered a dark film-set like a chamber in which a performer wearing an astronaut costume would periodically spray (fake) moon rocks with the synthetic smell.

Visitors would then leave the room carrying the scent on their clothes – just like astronauts re-entering the ship would discover it on their suits – and then spread it all over the building and beyond. Smells know no boundaries. Hard to contain, they escape and pervade spaces at the same time. This idea of infinite expansion is part of the reason why scent seems to be a relevant medium to address space and its ineffable vastness.

In 2005, French artist Loris Gréaud, known for creating uncanny, technological looking installations, reached even further away from Earth. For his work entitled Spirit, the artist was interested in bringing the smell of Mars to our nostrils. Although the Martian atmosphere is primarily composed of odourless carbon dioxide, its surface is thought to give off the not-so-pleasant aroma of rotten eggs, due to its significant concentration of sulfur.

To create the scent at the core of Spirit, Gréaud thus used atmospheric data gathered by the Martian rover Spirit, but also dug into anticipation novels to collect imaginary descriptions of the smell of the Red Planet, literally situating his work between science and fiction. Not interested in deploying any form of visual mimesis, the artist used a simple, technological looking, diffusion apparatus to keep the scent at the core of the work, and nothing more than a functioning nose was needed to step into this imaginary smellscape — a term coined by geographer J. Douglas Porteous in 1985.

Leaving the tangible grounds of satellites and planets, French artist Vincent Carlier was inspired by the intriguing scent of Sagittarius B2, a molecular cloud of gas and dust located some 39 light-years from the centre of our galaxy. Although Sagittarius B2 contains enough alcohol and noxious fumes to make you dizzy and nauseous, a significant amount of ethyl formate – a chemical responsible for the flavour of raspberries and rum – was also discovered in its centre. How could anyone have imagined that somewhere in the universe float such appetizing and familiar aromas? Drawing on this particularity, Carlier’s kinetic sculpture, Sagittarius b2 (2012), a three-legged futuristic stoup reminiscent of a flying saucer, emits a fragrant mist that spreads these celestial aromas in the exhibition space.

Mimesis used to be about images and representation. But for a few decades now, artists have invented a form of phenomenal mimesis, recreating nature’s wonders by intersecting with sciences and appealing to the whole sensorium. Also inspired by the discovery ethyl formate in Sagittarius B2, fellow French artist Laurent Duthion even created a culinary work consisting of white rum, raspberry syrup, lime, mint, water, alginate and calcium lactate. Entitled Approximation sagittaire (2017), the jellococktail virtually enables you to ingest a small portion of the cosmos.

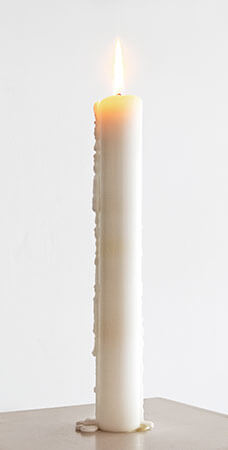

Right: Candle (from Earth into a Black Hole), Katie Paterson (2015). Exhibition view Frac Franche-ComtémPhotograph:Blaise Adilon, 2015. Image courtesy the Artist/Frac Franche-Comté, Besançon/ Ingleby, Edinburgh

While the whole universe might not fit in your mouth3, it is almost entirely contained in Katie Paterson’s Candle (from Earth into a Black Hole). Scottish artist Katie Paterson routinely collaborates with scientists and is known for grounding inaccessible concepts and objects in the tangible, physical reality – whether the sound of a dying star or the image of ancient darkness. In 2015, in collaboration with Steven Pearce, she created candles offering a 12-hour journey through space in 23 individually scented layers, each corresponding to a planet, an astral body or a place of the universe.

If some of these scents built on personal reports such as the burnt almond cookies aroma of the Moon described by space tourist Anousheh Ansari, others stemmed from more scientific sources such as analyses of the material composition of Venus or Jupiter. NASA notably supplied the artist with information collected by the Cassini spacecraft regarding the smell of Saturn’s moon Titan, a smell that they reproduced thanks to an unsettling mix of three aromatic gases: nitrogen, methane and benzene. But some of the scents used by Katie Paterson also came from more personal associations – for her, Earth smells like a forest and the stratosphere like geraniums –, demonstrating once again that scientific rationalization and fantasy always mirthfully meet when it comes to Space Art.

Paterson’s work beautifully takes into account the question of time and distance, deeply interrelated in space. The burning time of the candle condenses the deep time of the cosmos and brings it back to a human scale. And as the candle burns down, we travel up – navigating in space as well as in the mind of the artist. The idea of a change of scenery through smells isn’t new though. Not long after the infamous literary examples of Charles Baudelaire and Karl-Joris Huysmans, Japanese-German artist Sadakichi Hartmann organized, in 1902, a scent-concert entitled Trip to Japan in Sixteen Minutes where participants were taken across the Pacific Ocean by a succession of scents wafted by fans through the theatre. The sense of smell has the power to instantly take us where we’ve already been, but also where we could otherwise never go. And there’s no need for Scotty to beam us up: it is as simple as closing your eyes and breathing.

While images offer a frontal, distanced experience, smells do not only surround you, they envelop your skin, penetrate your brain and body with every breath you take. Atmospheric, trans-corporeal, these olfactory artworks offer what might be the most embodied experience of space that one is likely to have. An utmost impossible experience one might say, for even in space, none of these chemical compounds would be smellable. Fortunately, contrary to science, art has the power to open wormholes in the fabric of reality.