Words by George Vitale

For most of history, technological change unfolded slowly—centuries of incremental advances refined and built upon existing technologies. However, the speed of development of Virtual Reality (VR, i.e. hardware and software) is quite different. Its rate of change is astonishing. I remember the specific technology that was on sale when I founded synthesis three years ago: it has evolved dramatically since then, with each iteration dramatically closing the gap between the real and the virtual. Technology is propelled by turbo capitalist forces: it is radicalized by and then, in turn, radicalizes them. Simultaneously, I have witnessed a relentless race to create the next spectacular VR experience. The public records are full of examples.

A VR experience is a descriptive phrase that is fluid, vulnerable and can be applied to a panoply of things. Almost anything can be described as a VR experience if it unfolds in virtual reality. Michel Houellebecq has not expressed an opinion on VR yet. Still, I do find a connection with what he writes on Platform regarding the storyline of our decadent modern life: an experience-based one. From fine dining in exotic restaurants to journeys towards tropical destinations, experience has become the ultimate fetish for profiteers and influencers.

On the experience

An experience can be broadly defined as any unique process characterized by having both a beginning and an end. It ceases only when the energies propelling it have resolved themselves. Every part of the experience flows fully in an unfolding present tense. John Dewey in his ‘Art as experience’ goes further, stating that an experience has “its own unity,” defining and qualifying it – that meal, that storm, that trip – despite any variation in its constituent parts. It can be emotional and/or intellectual and it may or may not carry esthetic value.

While an emotional experience (i.e. fine arts) focuses on material qualities related to the esthetic, the intellectual experience – an experience of thinking – simply refers to the fact that the experience has intentional meaning. Nevertheless, for an experience, emotion is the moving and cementing force. According to Dewey: “it selects what is congruous and dyes what is selected with its colour, thereby giving qualitative unity to materials externally disparate and dissimilar”. The experience relates to art in that an artwork concentrates, elaborates on and enlarges upon an immediate experience. Art treats experience as metaphor and symbol – as meaning or signification – something beyond pure sensation and perception. A work of art is a thing, whether or not it is a physical thing, a thing that is filled with meaning and thought.

Art as experience

As VR art fuses art, technology, and design, a recurrent confusion in the objectives of each is frequently noted. In other words, the problems that are solved by art are very different from those that are solved by technology (when its goal is use and utility) or design (use and utility with a stronger accent on the aesthetic).

Michael Takeo Magruder, a pioneer of VR art and an artist with whom I have worked closely in the recent past adds: 21st-century technology has of course greatly expanded the artistic possibilities for virtual worlds and experiences, but it has neither created the context nor started the conversation. The core notions of virtual reality – like illusion and immersion – are clearly woven throughout our collective past as evidenced in Roman frescos and prehistoric cave paintings.

Such ancient art forms were also aligned to the newly developed media of their times, and like now, those technological innovations provided a means to render artistic visions in novel ways. But novel applications of media have never been the purpose of art. Art – whether virtual or otherwise – is grounded in meaningful exploration and expression, not technological spectacle.

Commodity fetishism and its spectacularisation quintessential elements of the society of the spectacle that once brought Donald Judd to state in resistance that art is intrinsically a matter of quality, to distinguish it from consumerism and goods of mass production. I find this point to be crucial, especially in digital art as the technological fetishism surrounding its processes (i.e. AI) or the medium (i.e. VR/AR) often becomes more important than the outcome of those processes themselves (i.e. the artwork).

Katharina Haverich, an emerging artist working in VR who considers herself a hopeless aesthete, shares the same frustration: Taking my stuff to recently established new media sections of several festivals has made me realize that people can get offended if you don’t exploit the “new” medium to the fullest. I find that amusing. It is like if you do not colour every pixel in the VR Headset, you get a bad grade. Nervous VR hunters set up terabytes of storage and put out some semi-delicious bait. If your work cannot be reduced to ones and zeros, you have a problem in the VR Art World.

VR Utopia

Although the first VR artworks date from the ’90s, VR as an artistic medium has only gained traction and momentum in recent years. I claim that is because society was not ready, meaning not as blindly addicted to digital technologies as it is today. VR offers a magnified parallel, visual, and alienating world precisely expressing the current times.

Another sensational product, a fast-moving, seductive simulation, with the goal of stimulating consumerism. A digital simulation, by definition, must be more appealing than real life. Consciously or not, we pour our real lives into the digital every day as we mediate it through all of our hyper realized means of communication.

Our lives seem to exist simultaneously on several simulated platforms: Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Zoom, etc. Claudia Hart, one of the most important representatives of digital art argues: I came to understand that whatever the new technologies of representation are at any one moment, those that wield it, believe they are building a new kind of heavenly Utopia. I think the ephemeral nature of VR, the feeling of being real and unreal at the same time, lends itself to this heavenly guise. And artistically, when you bring an audience into a space that holds onto this edge (i.e. dreamlike/ghost-like), users tend to feel that they are having a kind of transformative, heavenly experience.

But isn’t this what art generally should have as its mission! For me, the glitzy, sensationalist, sexy-product idea of VR is all wrong. Not quite “arty” enough for my gusto. It should be more of a spiritual journey. And I am sure that the more personal and economical means that artists embrace out of economic necessity are also to our advantage. I am quite happy to leave the blockbusters to entertainment, pedagogy, and science.

On curating VR

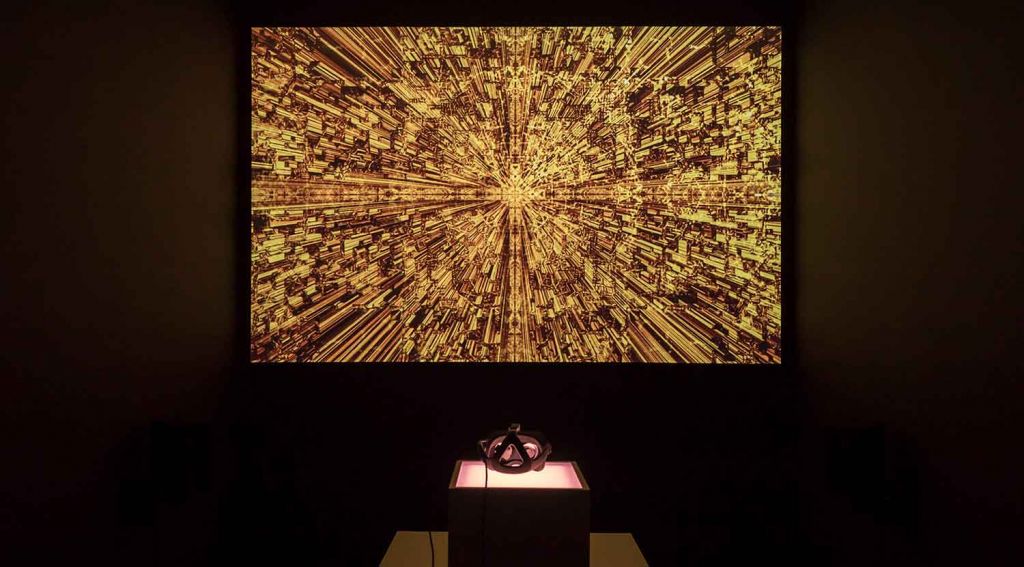

When I enter an art gallery, I search for beauty. I am hunting for it. I think that we all do. And think of how disappointing it would be if visitors walked into an art gallery and found only a headset on a table. That would look awful and be awfully disappointing. Yet to my surprise that is how VR art has been frequently presented in prestigious art fairs and exhibitions. I expect the experience inside of the VR headset to begin only as the experience outside ends. Visitors need to be introduced to the VR piece by the means of the outside experience.

What makes a VR artwork is the fact that it should be the VR technology plus something else – from paintings and sculptures to an A/V set up and performance art. Exhibiting VR next to more traditional art forms has a double benefit: it promotes the new medium and normalizes it as art in the eyes of the public. Moreover, VR paves the way to new exhibition formats which is a captivating opportunity for both curators and exhibition makers. A challenge that should be embraced!