Words by Charlotte Kent

The borders of my life these days extend to the perimeter of my apartment in New York City. Living with someone who had been tracking corona since early February, after attending a week of art fairs, I went into isolation on March 11th. Shortly thereafter the city outlined shelter-in-place procedures, and those recommendations have already been extended to the end of April. Personally, I don’t see leaving before June 1st––at the earliest. Occasionally, I open the windows.

Borders, in such a context, seem particularly strange and abstract. I have video conference meetings with students, colleagues, artists, friends, and family. Friends who live a block away and those on the other side of the planet. Some days I see people more, or at least more intimately, than before. At the same time, I learn that New Yorkers are being turned back when they try to leave the state. This is true in other countries as borders become a means of containing this bizarrely varied virus.

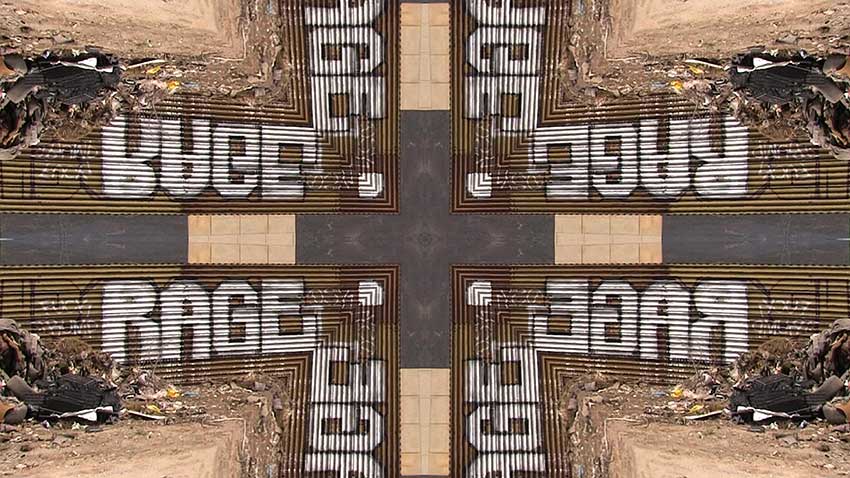

In a recent conversation with the artist Peggy Ahwesh, we spoke about the concept of borders as they apply to nations and narratives. Her 2019 exhibit Cleave, at Microscope Gallery, brought together recent works that circled around the theme. Border Control (2019, 4 minutes 10 seconds) placed four flat screens in a square formation to showcase the San Diego, USA and Tijuana, Mexico border. Ahwesh filmed from the Mexico side where she could see the eight prototypes of the wall that Trump heralded across various media outlets as necessary to national security. He never picked a winner; eventually, the prototypes were dismantled, an expensive spectacle.

Ancient cities had walls to keep out invading armies. They presented safety and a home for those who lived within them. Those walls also did the work of defining us and them. Borders have real and metaphoric constructs. In Ahwesh’s new media work, she uses a kaleidoscopic effect that disorients the viewer even as she captures a man who climbs over one of the walls and slips into the United States. She tried to warn him as she had seen security trucks regularly, and surveillance cameras seemed plentiful.

If she could be standing there filming, this did not seem like a good place to jump. He was from Ghana, however, and had come far enough to keep going. As she describes it, his conviction is surreal to those of us trained to worry about authoritative gestures. She has no idea what happened to him next. The encounter was unexpected, ironic, and pointed. She crossed that border without effort and returned to the wedding festivities that had her in that part of the country shortly thereafter.

The root of border finds itself in French as the broad-coloured band that surrounds a shield. Only in the 14th century does it apply to the boundary of a city or region. In the United States, at the beginning of the 19th century, it came to mean the line between the settled regions of the country and the wilds beyond. That man doesn’t seem half as wild as COVID-19, a disease that ranges from being completely asymptomatic to horrifically deadly. The invasion of this virus is bringing nations to a standstill.

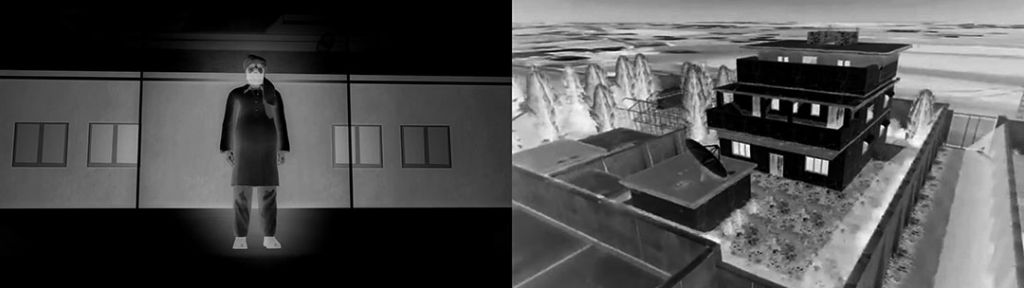

Trump tried to nationalize corona with various spurs at China, and then claimed that his opponents’ “new hoax” was to politicize the disease. Politics always has so many versions of the same story; history is the narrative of those who win…though they might not agree on how they won as Joseph Strick showed in his 1970 documentary Interviews with My Lai Veterans (1971) in which five American soldiers recount their experiences, revealing very different memories of the same events. Ahwesh’ “Re: The Operation” (2019, 8 minutes 2 seconds) put in dialogue the official stories of the capture of Bin Laden. The narrative fractures as attempts to maintain ideological stances conflict with events. The challenge of subjectivity is that it reveals complexity. As with other issues, Trump’s inconsistencies in addressing coronavirus make any official narrative more difficult.

In this moment, even those who distrust metanarratives or authoritative accounts want one. The spectacle expands from one media channel to the next as people at home try to get a semblance of information about what is happening and what to expect. But, there is no omniscient paternalist figure to comfort and control. Instead, we are suddenly the adults in our own lives, responsible for the safety and sanity of ourselves and each other.

Wash hands with hot water and soap for at least twenty seconds. Reach out to those who are alone by phone or through the Internet. Mind your thoughts. And maybe, reflect on the presence or lack of government resources to help those who need it most and whether the political institutions that we largely ignore and occasionally vote for are doing what we expect of them. Beyond the walls of my home, there are city and state and national borders where rules about entry become more stringent. We hear that refugee camps are not getting the basic supplies, like soap, that they need. The us versus them becomes crueler when resources seem limited. Borders become figurations of an attempt to control what, in this instance, is invisible to the human eye. Borders project a sense of ownership for people who have nothing and need something to claim, Ahwesh explains.

The new containment regulations and recommendations reveal those most vulnerable, who have truly nothing. The homeless of the nation are more evident now. We may leave our homes less frequently but we see them more. This virus is deadly, with major efforts going to provide a cure, but it is a plague that has also revealed our cultural indifference to so many. As the virus spreads to other parts of the world where health care resources are in even shorter supply, we know that it will likely return where it has already been felt. The humans there, far away, across an ocean, are just like us; their health is our health, too.

The virus that sweeps across planes and plains has a sophistication that our border walls fail to achieve. Their awkward mass is in another register than the microscopic virus. Shelter in place mandates are an important first gesture to contain the spread of the virulent disease. That can only be the beginning of how we think about this situation. Interestingly, the term containment reveals that the core of the issue is to manage ourselves. Containment is about administering to what is within the walls. We are the carriers that need to be restrained. The borders also exist to protect them from us.

Living within my own home for weeks on end now with no end in sight, I think less of myself as a national being and more as a fragile human being. I am no different than those singing on their porches in Italy, or sheltering from the rain under stairwells with no place of their own. I worried about sufficient soap and so have some inkling of the terror that prisoners without basics must face. In my isolation, many borders between me and them have been stripped. The challenge will be to maintain that awareness as the pandemic appears to wane.