Interview by Bahar Emirzade

Generative art refers to the use of an autonomous system to produce artwork. Hence, such a system can either be the work’s creator or a tool for its making. Despite what you may think, generative art is not a new concept. The pioneers, Greg Nees and Frieder Nake started their first exhibition in the 1960s1.

The exhibition titled Computer Graphik was the first one of its kind, and later on, the artists experimented with sculptures assembled using computers for architecture. Computer Graphik sparked the debate of whether generative art is art. Since then, there have been many concerns about whether computers could be part of modern art and how we define art, to begin with.

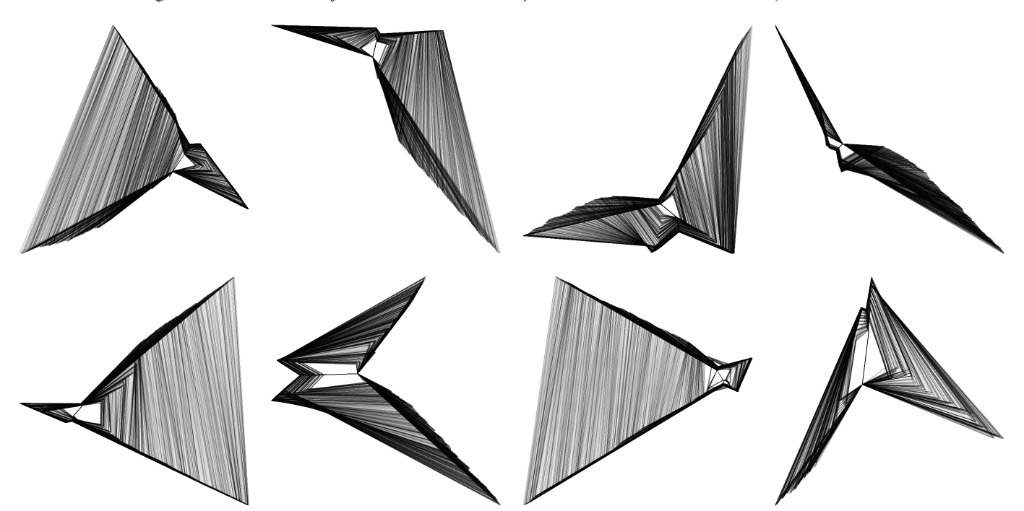

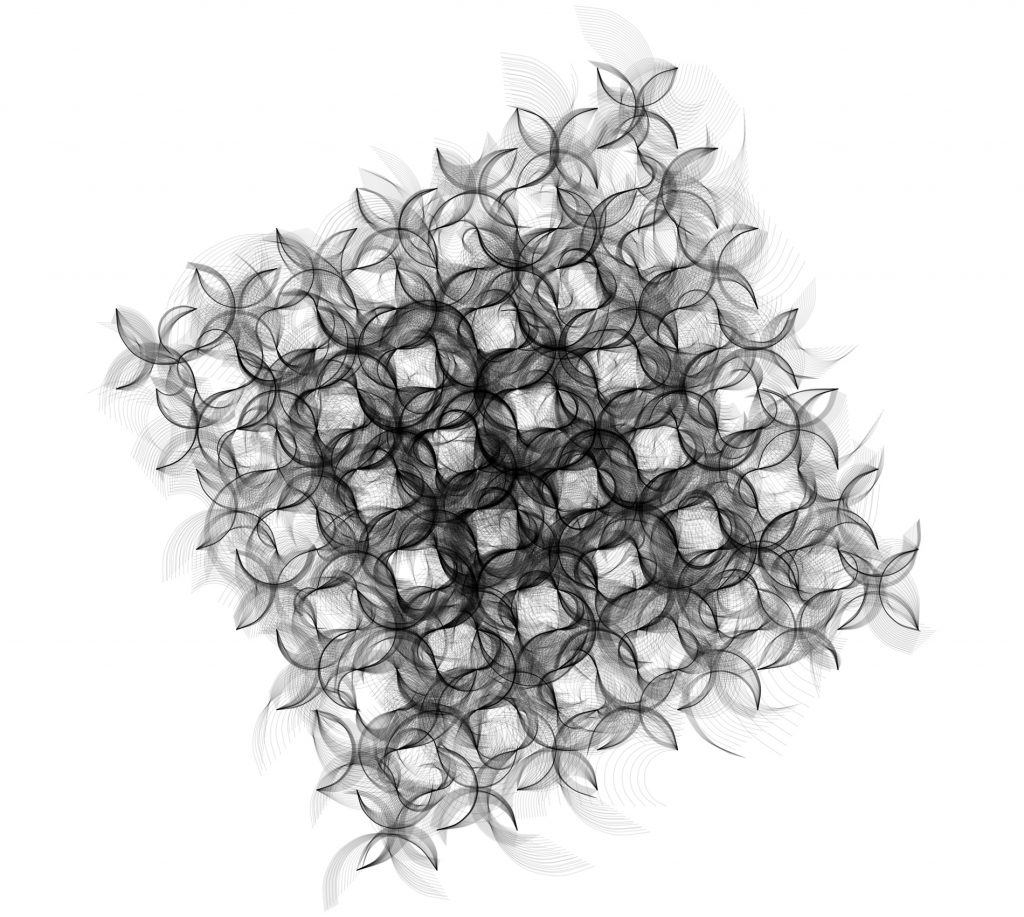

Cellular automata– influenced by Von Neumann, the father of game theory, is one of the most inspiring works of Marcus Volz. As a mathematics researcher at the University of Melbourne and an artist whose interest began upon realising the aesthetics of computational geometry, Marcus Volz is a fresh breath to generative art. As a tool of his artistic work, Volz uses various coding languages such as R or gg2.

His Cellular automata displays the pieces; Universal Turing Machine, Langton’s ant simulation and Turmites, all produced with a similar main idea where each cell is set up with a certain rule, being able to self-replicate accordingly. The resulting images are a great demonstration of science being stirred into art. Volz’s generative art displays the analytic nature of science used in an emotional perspective; despite its conventionally stolid application in research.

The definition of art has been a controversial topic of discussion among academics and art enthusiasts. “The ten questions relating generative art”, a paper published by McCormack, proposes intricate arguments for both camps2. However, regardless of the definition of art one may prefer, it is still unavoidable to think whether a computer can ever be entirely original. Or could we assume that even a person can create something completely original?

In a time when creativity on its own is a shaky term, how can an autonomous system possibly produce a unique and creative piece? Yet, even though these questions are left unsettled, we can still enjoy the elegance of Volz’s computer-generated Turmites.

1 Boden, Margaret; Edmonds, Ernest (2009). “What is Generative Art?”. Digital Creativity. 20 (1/2): 21–46.

2 http://jonmccormack.info/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/TenQuestionsV3.pdf

Your artistic work is based on generative art and data visualisation. How and when did the interest in these disciplines come about?

My interest in data visualisation began about 6-7 years ago when I first noticed that data scientists and artists were creating beautiful visualisations and artworks from large complex data sets. At the time, I was working in a role that required a fair amount of data analysis. So I started to look for opportunities to incorporate visualisation into my work.

I soon realised that I would need more sophisticated skills to create the types of things I envisaged, and I began to focus on improving my programming skills. Over time, my domain of interest expanded beyond data visualisation and into various mathematical fields. Generative art – art that is produced by algorithms – was one such discipline that I became particularly interested in after discovering Jared Tarbell’s Complexification Gallery of Computation.

What data sources do you use for your pieces?

In my current role as a mathematics researcher, I do quite a bit of experimental work assessing the performance of algorithms for solving challenging geometric problems. These experiments can produce large data sets that report on things like CPU time. Moreover, these data sets can often be visualised in unique and exciting ways to gain insights into the algorithm’s behaviour.

In addition, the inner workings of an algorithm can be further understood through animation, which also helps to verify that the algorithm is working correctly. Finally, the data is simulated programmatically rather than from an externally-provided data set for generative works.

What are the main challenges you face when using data to produce art?

Producing this type of art can require abstract thinking because the visualisations are created from code rather than produced directly by hand. In addition, it usually requires thinking ahead to map out how the code will be structured, and this intermediate step can inhibit the creative process.

Sometimes the most challenging part of the process is finding and manipulating the data into a form that can be visualised. Most of the time, I feel that I can convert an idea into a visualisation quite quickly. Still, at other times it can be pretty time-consuming to finish work if there is a particularly challenging programming issue.

One of the series of artworks that caught my interest is Cellular automata. Why the name? Could you elaborate on the intellectual process behind its inception?

Cellular automata are discrete models involving grids of cells, such as the chessboard grid. Each cell can take on a particular state, and the states change over time according to a simple set of rules. The most famous example is Conway’s Game of Life, in which each cell in the grid is either alive or dead.

At a given time step, a live cell can become dead and vice-versa, depending on the states of its neighbouring cells. For instance, a dead cell with more than three live neighbours dies due to overpopulation. The simple state-changing rules can produce interesting patterns, which I have found to provide a unique basis for creating artistic visualisations.

You are also a research fellow at the University of Melbourne, studying geometric networks, optimisation and computational geometry. Can you tell us more about your research projects and how the research relates to your art?

I work in a team that studies the optimisation of geometric networks, which can be used to model road networks, pipeline networks and VLSI chip design. Most of the problems we study are based on a famous problem in mathematics called the Steiner tree problem, which asks for the shortest network interconnecting a given set of points in space. Because of the geometric nature of the problems we study, there is much opportunity to visualise the networks and other geometric constructions that arise from mathematical theory.

I have found that visualisation has been beneficial to our work in that it has sometimes revealed unintuitive and unexpected insights that have led to discoveries and allowed the research to take on new directions. In my spare time, I have taken some of the visualisations from the research and turned them into more artistic works.

What directions would you like to take your work into?

I am deeply interested in 3D visualisation and animation and am very focused on developing skills in this field. However, while the tools I use are very powerful for generating 2D visualisations and animations, their 3D capability is relatively limited compared to some of the advanced 3D software that is available.

Pairing 3D visualisation with my data visualisation/mathematics skills will hopefully provide a unique skill set that will allow me to produce highly detailed, original and unique artworks that combine knowledge and understanding from both fields.

One for the road… What are you unafraid of?

I would say that I am certainly not afraid of running out of ideas for new visualisations/artworks or experiencing any artist’s block. I have a growing backlog of ideas I want to explore, and often the most challenging part is deciding which idea to pursue next.

Whenever I come across an idea or concept that inspires me – from a book, lecture, video, etc. – I immediately want to visualise it or reconstruct it and expand it creatively. But, of course, this can lead to a lack of focus and discourage large, longer-term projects. Still, on the other hand, it allows me to cast a wide net in my exploration of mathematical visualisation and learn new things from various fields.