Words by Meritxell Rosell

During German Romanticism (the dominant intellectual movement in the philosophy, the arts, and the culture of German-speaking countries in the late-18th and early 19th centuries), there was a turn towards nature and its inspiring mysteries. For romantic literature, music, and art, Nature was a dynamic presence, at once enigmatic and anthropomorphic, engaging man in a dialogue with the life force itself.

Likewise, thinkers from the Romantic era conceived nature and culture as similars and sought to harmonise the sphere of the natural sciences (Naturwissenschaften) and the sphere of the humanities (Geisteswissenschaften).

German idealist philosopher FWJ von Schelling is a central figure in the development of Romantische Naturphilosophie. Schelling held that the divisions imposed on nature by our ordinary perception and thought do not have absolute validity. Naturphilosophie was, therefore, one possible theory of the unity of nature. A philosophy of nature [1] alongside transcendental idealism [2] would be two complementary portions making up philosophy as a whole.

Ben Woodard, an American philosopher with a PhD in Theory and Criticism from the University of Western Ontario (2015), focused his PhD thesis on Schelling’s Naturphilosophie [3]. More broadly, his work focuses on the concepts of dark vitalism and nature in German Idealism, philosophies of becoming, and Speculative Realism, stirred by his interest in horror and weird fiction and film. He writes about all these topics in Naught Thought, a contemporary philosophy blog.

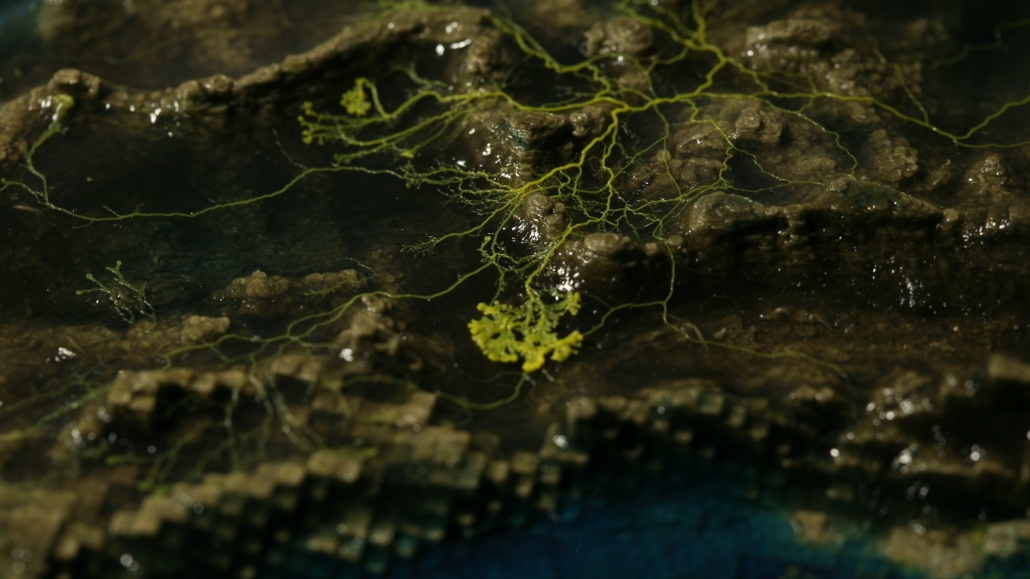

Woodard has also explored these themes in a number of books. One of them caught our attention a while ago, Slime Dynamics: Generation, Mutation and the Creep of Life (Zer0 books, 2012). In it, the philosopher argues that “slime is a viable physical and metaphysical object necessary to produce a realist bio-philosophy void of anthropocentricity”.

Including chapters with names as suggestive as “The Nightmarish Microbial” and “Fungoid Horror and the Creep of Life”, it explores Naturephilosophie, speculative realism, and contemporary science. Through his analysis, these concepts bring about a theory of dark vitalism which seems to be a theory of the Oneness of life pierced with the slimy and disgusting actualities of biological existence.

Novel socio-politico and philosophical disciplines like biopower, biopolitics and biophilosophy seem to be taking inspiration from nature, living organisms and biological systems (which call back to Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari Rhizome’s theory [4]). We should see if, as Ben Woodard points out, they are able to combat some of the ways in which certain strands of phenomenology (particularly its more theological variants) attempt to de-physicalize life.

At CLOT Magazine, we became interested in your slime dynamics theory, where you remind us that humans “like any other polyp of living matter, are nothing but heaps of slime slapped together and shaped by the accidents of time and the context of space”. Where did the inspiration for a biological system come about?

The general thrust of the book that life could be crudely defined as biology complicated by space-time is a reaction against how life appears in much contemporary and modern philosophy. In phenomenology in particular, life is associated with immanence, or equated with experience, or with a transcendental ego, and this did not make much sense to me.

In this sense, biology was an obvious place to go, to look for how life is by no means merely reduced by the biological sciences but that many of our philosophical concepts of life lag laughably behind the fascinating discoveries of the biological sciences.

This is not to say that the sciences, or a particular science, direct philosophy completely. I am of the opinion that philosophy still has a role in questioning and testing the conceptual grounds that the sciences utilise to ground their claims. At the same time, this does not mean that philosophy can effortlessly pull the rug out from under biology or any other domain.

For me, slime dynamics is not a theory in itself but a part of what Schelling and others would call Naturphilosophie. Naturphilosophie is not exactly a philosophy of nature nor a naturalisation of philosophy but what emerges from the combination of these tendencies. In this regard, the thinking of life and the life of thinking are chiasmatic in structure.

Deleuze and Guattari developed the concept of Rhizome based on the botanical rhizome, and you described the slime dynamics theory. Are there any other philosophers using biology as inspiration? Could these be grouped under a name like Biophilosophy?

Biophilosophy is an area of research that I believe is very fruitful, particularly as it combats some of the ways in which certain strands of phenomenology (particularly its more theological variants) attempt to de-physicalize life.

Eugene Thacker’s work is particularly useful in that he manages to absorb many of the useful concepts from biopolitics on the one hand, and from biophilosophy in its more philosophy of science form, and combine both in relation to the work of Deleuze as well as medieval thought and contemporary problems in continental philosophy.

So I think biophilosophy can function as a grouping of similar interests, but it should be wary of becoming an -ism or a position for its own sake. This would no doubt lead to an over-focus or valorization of life that would undermine its very usefulness.

If you had the choice of being born in any period throughout history, in which period would you choose?

To say the far future is very tempting, but that is a bit more of a gamble. My first inclination is to say the early 1800s since that is a period in time where my mind drifts most. I have many dreams of being a Naturphilosophen, doing experiments on electrochemistry, and being able to be a scientist and a philosopher in equal measure.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

Non-isolation.

You couldn’t live without…

The electromagnetic field of the Earth.