Interview by Marielle Saums

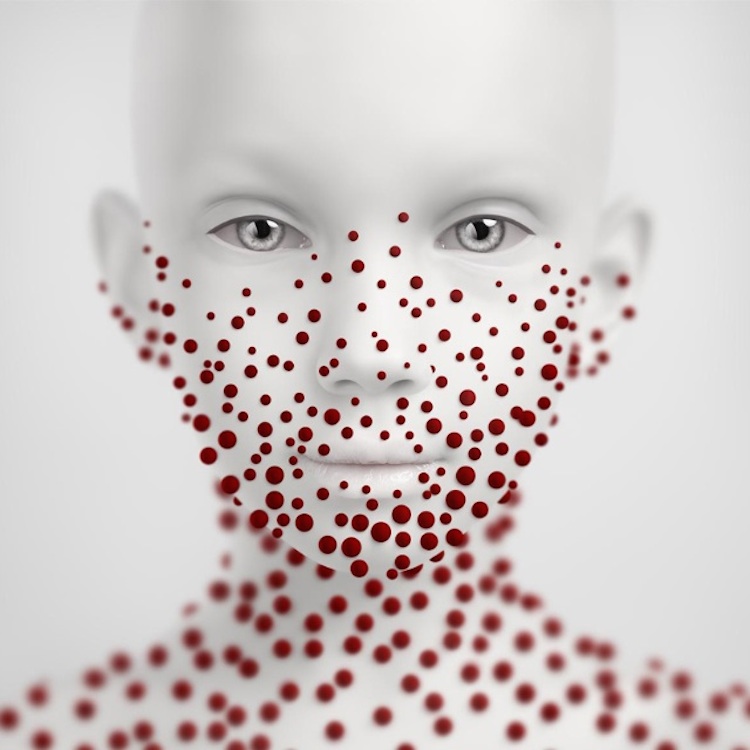

Oleg Dou’s photographs and sculptures are often described as grotesque and repulsive, but the unsettling nature of his heavily edited photographic portraits derives from monotony and emotional distance. Dou places his work within the context of French philosopher Gilles Deleuze, who asserted that identities fluctuate in response to changing social forces. As an artist who blurs, stretches, and collages faces to the brink of beauty standards normalised by popular culture, Dou’s explorations of identity also enter the realm of body horror.

In Deleuzian philosophy, the body without organs is a peripheral state that is revealed when we strip away the effects of various social conventions around the body. Dou’s art grapples with unstable body image, often adding strange appendages and surfaces to his subjects using materials in the studio or in digital postproduction.

Dou’s florid works are saturated with gory details. A genre of excess, body horror tropes often stems from a fear of losing control over one’s body due to mutation, disfiguration, or other causes of unwanted transformation. Dismembered genitalia is draped within a classical still life of fruit in Royal Testiculus (2016), horns protrude from a boy’s head in Narcissus II (2016), and the The Mushroom Kingdom series (2013) features porcelain figures with grotesquely flaccid limbs performing disturbing acts. While his subjects often command direct eye contact with the viewer, their gazes are uniformly empty and resist the warmth of personal connection.

The narrative of Dou’s artistic development focuses largely on his fascination with extreme retouching and florid morbidity derived from Victorian-era aesthetics, but frequent allusion to fables connects his work to a greater cultural fixation on manipulated bodies. Dou’s corporeal anxieties are echoed in contemporary art mainstays like Matthew Barney’s The Cremaster and pop culture touchstones like the young adult science fiction series Animorphs, all of which construct highly personal fables that explore body horror at stages of transformation between human and animal states.

Dou describes social isolation and disconnection from his own body as forces that overpowered his earlier work, and are reflected in the solitude of his artistic subjects. While he is critical of socially imposed ideas on how to express happiness, his work does not reveal alternative ways to express joy and desire or regain a sense of bodily control. The body without organs emphasises that all identities are effects of difference, but the distinctions that Dou’s work emphasises don’t always clearly interact with sociopolitical values placed upon bodily traits such as skin color or gender.

His sometimes formulaic process of editing images of people down to similarly cartoonish proportions and pasty complexions can enforce rather than push the established degrees of difference discussed by Deleuze. His more recent sculptures, such as Love Maniac, evolve upon earlier series to have a more sophisticated representation of Deleuze’s body without organs through disassembly and rearrangement.

His interview responses can be elusive, often ending with indecisiveness, but provide flashes of vulnerability. Dou cites personal authenticity as being important to creating good artwork, and it will be exciting to see which personal qualities he chooses to explore while continuing to focus on retouching photographic images. Perhaps he has not yet articulated his own relationship with his corporeal self, and his future artwork will reflect his still-evolving concatenation of bodily possibilities.

The inspiration comes from the 19th century tradition of capturing child funeral portraits. For those that are not familiar with your work, could you tell us more a bit about your background and this inspiration?

One of my primary interests is about forms of representation in daily life and culture. I was always afraid of being photographed when I was a small kid, and I still do. I can’t smile without reason just for a photo. That is the point where my artist research comes from. If you remember advertisements from TV or magazines, you can notice how consumption is connected to happiness.

I mean, we should think it is connected. Also, we got an idea of how to express our joy. It becomes evident with all social media networks like Instagram, where people copy scenes from movies, advertisements or magazines. They do photos of champagne glasses and expensive clothes, and they even copy body positions to show how cool and successful they are.

This “smile” culture was rising during the 20th century through marketing, but for me, it is more about the body control of the people. A few years ago, I found a collection of 19th-century funeral portraits. The interest was not in death but in the strangeness of the practice for the modern days to show how different representation could be.

You use photography as a medium, but you define yourself as an artist rather than a photographer. When and how did the fascination with photography come about?

It happened in 2005 when I got my first camera. I was working as a designer retouching photos for clients. I would not say I liked this job because the pictures were awful. So I decided to buy my camera to do and retouch my own work. But I also do video, sculpture, installations and even perform. That’s why I’m an artist.

From performance artists (like Marina Abramovic) to body artists (like Stelarc, ORLAN and P- Orridge), the body is/has been used as an open space for dialogue. With the term ‘body without organs, ’ Deleuze describes a relationship to one’s real body as an abstraction of corporeality. In your work, you used traditional photographic techniques with photo manipulation to transform human faces to create unsettling and airbrushed skin creatures giving them a new identity. What does the body mean to you? What interests you the most when creating these oneiric images?

The strongest fear we can experience is the fear of death. Our mind tries to avoid it in different ways. In the Western culture based on Abrahamic religions, there is a concept of the soul. This is the idea that we are not our bodies but something else inside that will not disappear with body death.

From this point, body and mind conflict because they are separated. Also, that also comes from the mass culture, the “idea” of a perfect body that we can have but never achieve.

Also, all that mixed with the traditional culture to hide the body as something shameful. I’m looking at my body in the mirror and far from being happy. I try to overcome it, but honestly, I don’t know how. The characters from my pictures are like perfect creatures having bodies, but not incorporeality, not biological. I also do some objects in silicone and explore lacking natural feeling in my photos. I try to balance it somehow. But now I’m only searching the way and have no answers.

One of your latest works is Heaven In My Body. Could you tell us a little bit about the intellectual process behind it?

You can notice that in my early works, I was taking photos of kids and women. No photos of men because the way I retouched pictures worked well for kids and women but not for men. I tried, but they looked too gayish and mannered. I’m gay, and I noticed I had some inner conflict that was obvious with my male portraits. So for the Heaven in my Body series, I did not care about this feeling and experienced joy doing this series. Being gay is not the central interest in my artist research, but the more you are yourself, the better for the work.

What directions do you see taking your work into?

I have a few plans for future work. I will continue to do retouched photography, and I will try to make the full body or even group images that I haven’t done yet. I’m going to make a short video essay, some new objects and some furniture as well.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

Too much attention to others’ opinions can hurt creativity, although creativity itself is often connected to the expression of others. That’s why balance is necessary.

You couldn’t live without…

Sleeping well.