Interview by Isabella Ampil

When Greg Orrom Swan muses that he is absorbed by the minutiae of the everyday, he succinctly captures the question that this magazine has always sought to answer. What is the essence of curiosity that unites artists and engineers?

There is a beauty at the core of the two fields that have created Nobel-prize-winning scientists who are at the same time lauded musicians or famous actresses who do biological research on the side. Swan, like any good engineer, likes understanding complicated systems down to the scale of their smallest components. Like any good artist, he finds details compelling and wants to share their beauty with the world.

It is not surprising, then, that he just finished his Master’s degree at the Royal College of Art, London, in Information Experience Design, a program that emphasises the humanistic side of computer science, heavy in artistic inquiry as well as technical study.

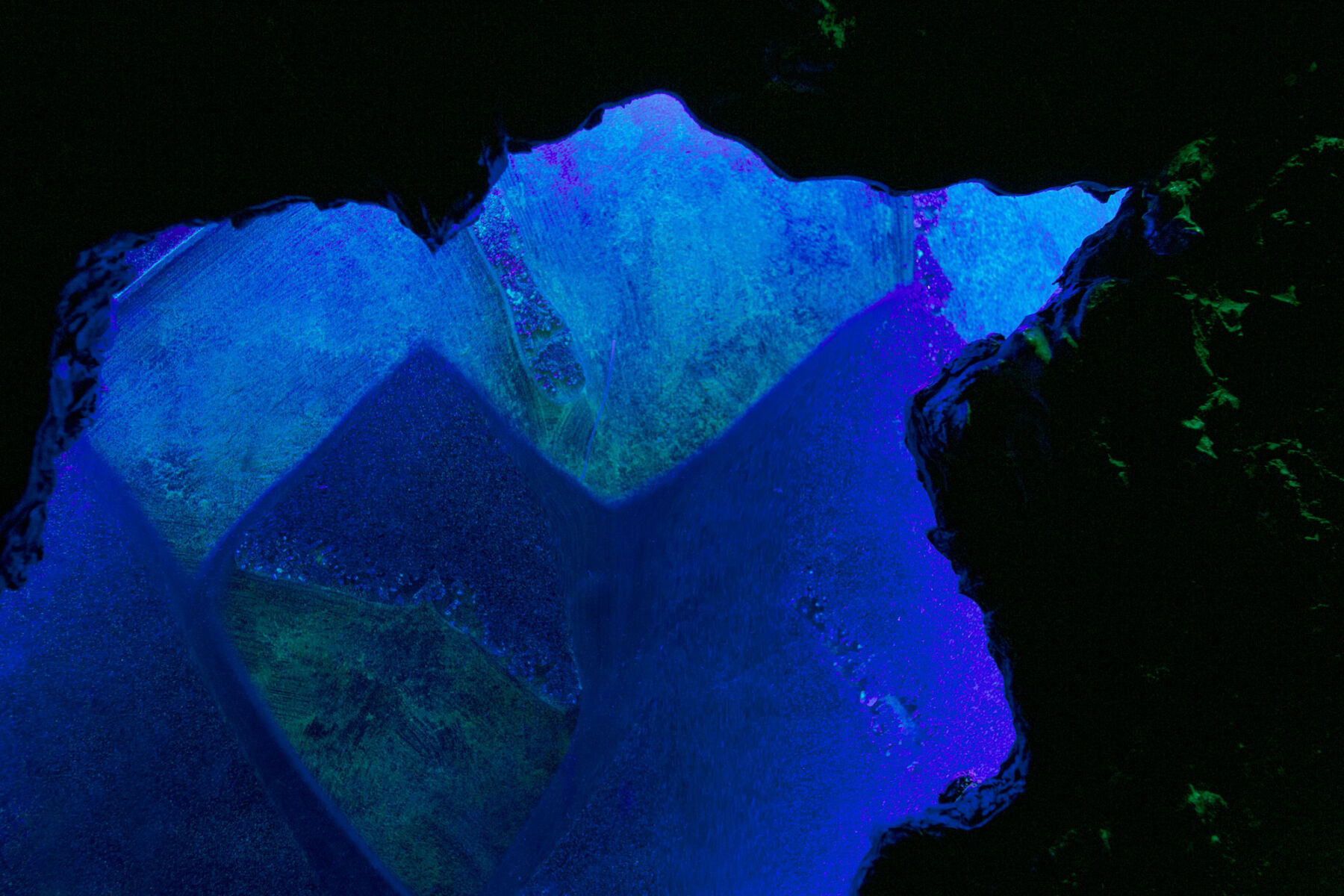

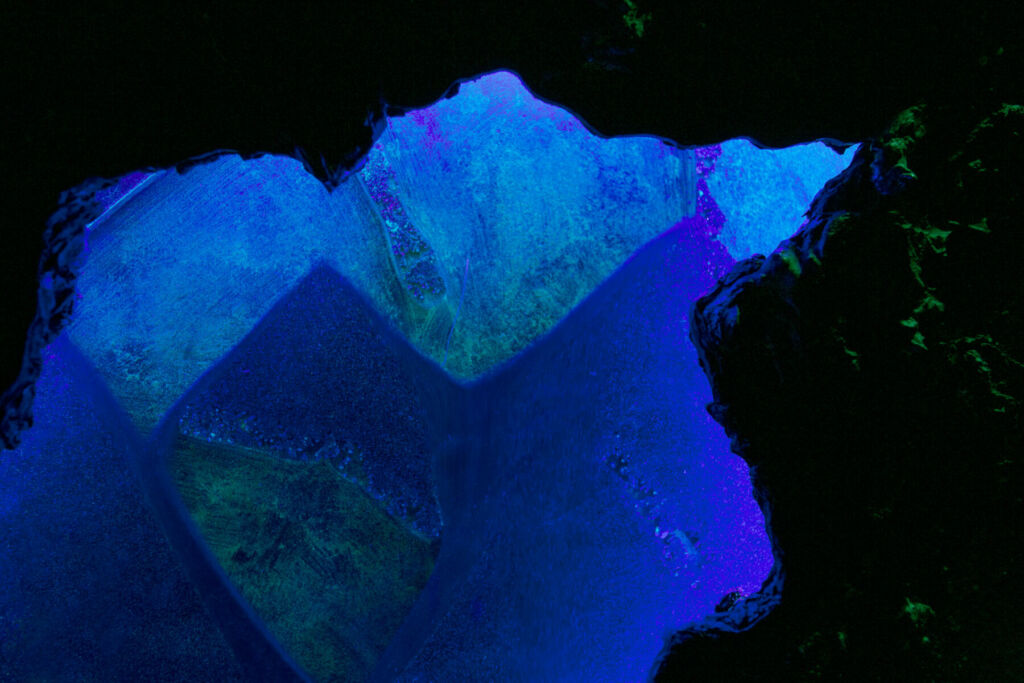

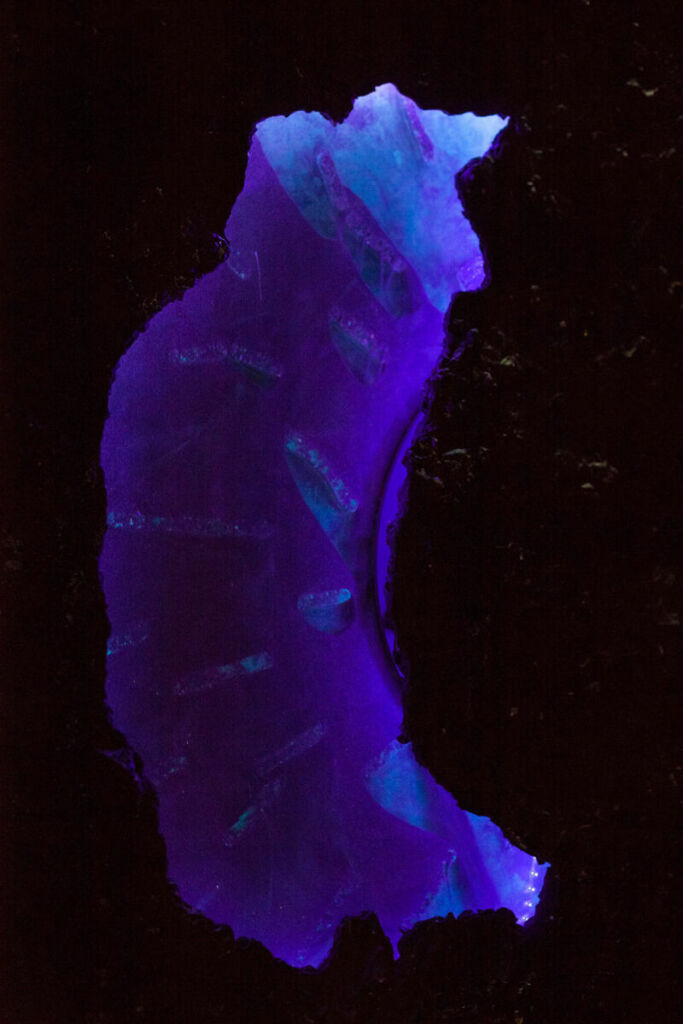

His A Measure of Minerality, a gorgeous sculpture – although such a term doesn’t capture the immersive experience that it provides – made of phosphorus, puts his training in the former on display. Its colours shift wildly in temperature, giving an alien appearance to crystalline structures that are connected in organic forms reminiscent of corals.

In Pigeon Vision, a set of glasses that would be perfectly trendy if not for the frosted bit of plastic that sometimes hangs over the user’s eyes, he gives fans a taste of his sense of humour. Pigeons have to bob their heads back and forth while walking in order to see clearly; they experience blurred vision when they push their heads out, but while holding their heads in place to take their next step, they can see clearly. The glasses simulate this by allowing the plastic flap to hang over the user’s eyes while they are moving and causing the flap to flip back up when the user is still.

The goal of seeing like a pigeon, while whimsical, sounds much more profound when Swan explains it. In his pursuit of seeing human beings as distinct from nature but not superior to it, he has given us a tool for empathising with other creatures that may yet erode our species’ arrogance toward the rest of the world.

But Swan’s magnum opus is Olombria, a startup supported by the RCA and co-founded alongside Louis Alderson-Bythell in early 2017. To combat the deterioration of global honeybee populations, Olombria builds and provides the tools to attract more hoverflies to plants needing pollination. Hoverflies account for about 30% of pollination worldwide, which is vital to about 33% of the food we consume.

In addressing this issue, Swan studies biology and ecology, automation, chemistry, and sustainable agriculture, but he also studies beauty. His work is inextricable from flowers and fruit but also from compassion, from the problems humans make and solve for one another, and from the cycle of loss and creation. There are multitudes of stories wrapped up in his work, as in all innovation, but Swan seems uniquely equipped to handle their layers and complexities down to the minutiae.

In your statement, we read that in your work, you often try and look at humans as distinctly different from the nonhuman parts of our world but not above or dominant. For those that are not familiar with your background, could you tell us a bit about what your aims are as an artist and designer?

I see humans and all things as woven and enmeshed parts of this world. Each has a part to play and moves in relation to one another. As one of these humans, I see the position I am in, an artist and designer, as a problematic yet privileged place. On one hand, a position that contributes to the further use of resources, bodies, and materials every time an object is designed or created, and on the other, a position that has a certain agency to be part of the solution, or at least contribute conscientiously to the wider recognition of us as a single, but entangled part of this world. So, in a way, my aims are about trying to highlight this, or at least somehow show this.

I am absorbed by the minutiae of the every day—where things came from, how and by what means, which path this thing or that took. Much of my work attempts to focus attention on the journey, to express a detail, a nuance, a small part of something, always recognising it as being part of something bigger. I guess a systemic way of looking at things.

A Measure of Minerality is an immersive experience that explores the ‘material ancestry’ between human bodies, rocks and earth to highlight the geological time implications of material transformation on this planet. What is the intellectual process behind this project?

It started with the provocation: “We are walking, talking minerals” —a phrase of Lynn Margulis that Jane Bennett references in her book Vibrant Matter. I find this statement to be both profound and yet incredibly normal. It highlighted to me the literal and poetic composite of earthly matter we are as humans: the shared elements, the shared compounds, and the shared minerals. By normal, I don’t mean un-extraordinary. Yet, I feel it’s uncontroversial to state that we are a composition of various material parts, and it’s exactly this everyday fabric I want to express—the domestic human is a composition, just as everything else is.

I wanted to take a part of new materialist theory and express it in an artistic context framed around the heterogeneity of humans and nonhumans. So, I explored minerals and came across the mineralisation of mammalian (human) bone, as its mineral component comes from the mineral group apatite, all of which contain high amounts of phosphate (an oxidised form of phosphorus). Looking further into this, I found that from within the apatite mineral group, both human/mammalian bone and phosphate rock contain the same phosphate minerals (hydroxylapatite and fluorapatite) and that phosphate rock is often later processed into agricultural fertiliser.

Having these different physical arrangements of bone mineral, phosphate rock, and fertiliser come from different sources but having a shared minerality, I enjoyed the physical examples of matter, highlighting our earthbound nature as ‘walking minerals’.

Geopoetry (poetry about or with geology) and biogeochemistry also affect how I speak, write, and perceive the relations between biology, geology, and chemistry. The poetic and conceptual space allows me to attempt to communicate the often strange and lurid connections between the different assemblages of humans and nonhumans, highlighting our shared ancestry, minerality, and elementality.

What is more important: to take or not to take yourself too seriously to be creative?

I think it’s seriously best not to take yourself too seriously. Especially when trying to engage progressive thoughts about the world, you have to be serious, optimistic, and silly almost 88% of the time.

Solitude or loneliness, how do you spend your time alone?

At times both in solitude and lonely, I feel a heightened sense of confidence, freedom, and presence when I’m solitary, such as when I spend time reading in pubs, exploring caves, or deep frying paint. However, sometimes I’m alone, and I wish to share my experiences or talk to others. Also, as composites, when are we really alone? —there is always so much in and around us to avoid feeling alone.

One for the road… What are you unafraid of?

I don’t fear walking, talking, or minerals. However, some minerals are to be feared.