Interview by Lidia Ratoi

Texture. Colour. Material. Light. Movement. Sound. One morphing from another, seamlessly coming together. Suggestive. Empathetic. Delicate. Strong. Seductive. Impossible to separate all these instances. An overall delight, a magical world. So smooth, as if it were out of water. The work of Hong Kong-based Tobias Gremmler is all of these things and more. Having worked first with music before switching to a visual environment, Tobias understands movement and rhythm in a unique manner which only musicians interpret it. Inspired by theatre, where every single element influences another in real-time, Tobias’ videos depict motion in a unique way.

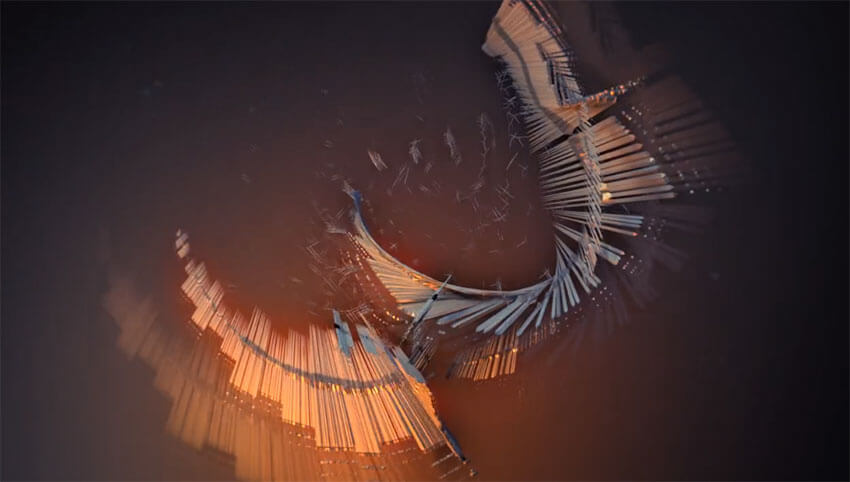

His most recent work is the videos for Bjork’s Loss and Tabula Rasa. Tabula Rasa depicts Bjork morphing in and out of “faun-like flowers” shapes, harmoniously transitioning from one to another. The video shifts from presenting this magnificent, transformative creature from face close-ups to overall body shots, with the metamorphosis passaging from completely surreal to human-like.

In regards to the video, Gremmler has stated that it “embodies the utopian concept of harmonious coexistence between nature and human-based on empathy”. And empathy is a common concept in his work. An artist who doesn’t shy away from challenges, Gremmler accepts projects ranging from visualisation of classical music, as in the case of his work with the London Symphony Orchestra, to those dealing with Chinese Opera or Kung Fu. He looks at these challenges with a child-like vision, accepting his own lack of insight into the subject and documenting to the point where understanding and empathy replace the feeling of novelty.

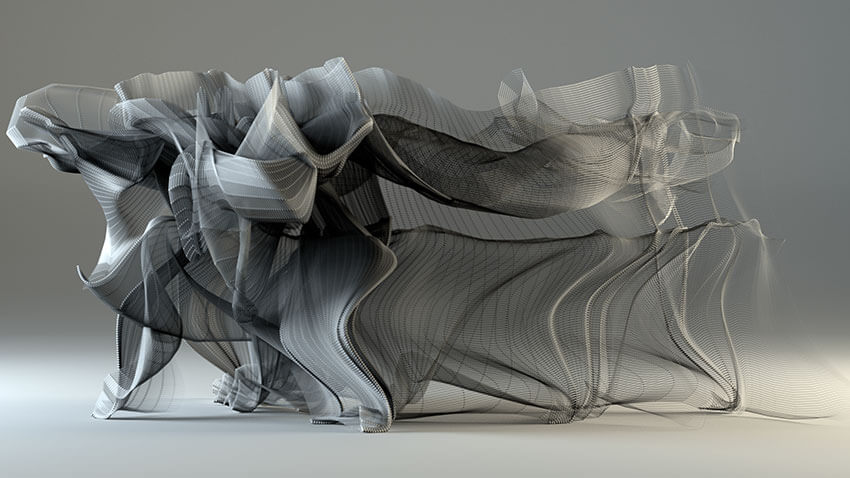

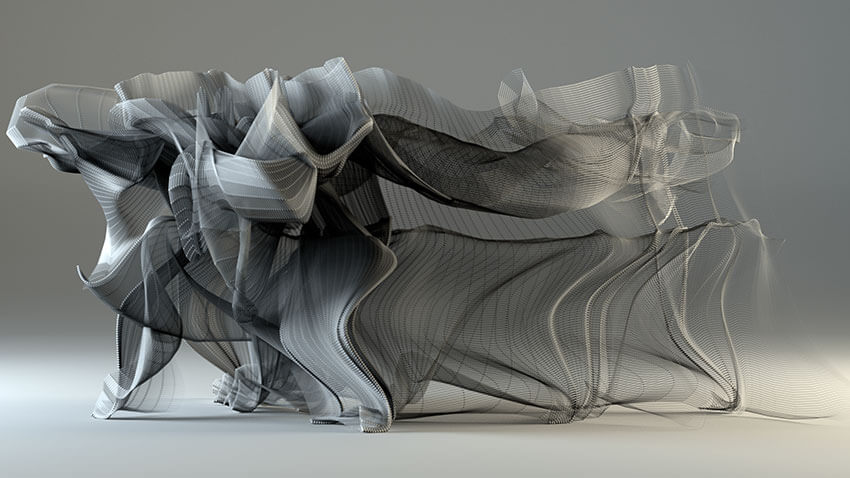

In his Virtual Actors in Chinese Opera, created for a Zuni theatre production that fuses Chinese Opera with New Media, the virtual beings display such ethereal delicacy, paired with the iconic precision of Chinese martial arts, that they seem not only real but seductive. The project deals with the idea of how “costumes and motions can virtually reshape a human body”, and the uniqueness that Gremmler offered each of the “actors” only further enhances the humanity he entraps in his animations.

As a Westerner operating from South-East Asia, Tobias Gremmler appreciates the interdisciplinarity of the Chinese culture, with one area influencing another. Similar to his own approach, it is precisely this loop between one field to another that makes each of his works an alternative but life-like universe. In his theatre show with Tim Yip, with sound design by Benjamin Teare, the line between imaginary and real elements is very thin but effortlessly jumps from one to another.

Creating digital counterparts of elementary materials like sand, bamboo, fabric, water, stone and smoke to emphasise aspects of the drama, these elements transform into landscapes, walls, warriors and dragons. Watching materials become creatures seems natural, and the actual humans performing on stage during the projection seem to be there as if to enhance the naturalness of this parallel world.

Making visible the “invisible information” of movement, Tobias Gremmler’s work is an invitation to a multi-scene party: the one that deals with what we know, the one that is completely imaginary, and the one which is triggered inside of us.

You work in design and media art, you write and handle digital communication, and are a researcher and teacher at the City University of Hong Kong. For those that are not familiar with your background, could you tell us a bit about it and how and when did your various areas of interest come together?

To me, those areas are interconnected. For example, I composed music for dance theatre before switching to a visual medium. Both areas are time-based, and there are many aesthetic coherences. I also learned a lot from the integrated approach of theatre. Every part influences the others. E.g. music, costume or lighting can impact the meaning of the scene drastically. Thus, it was essential to establish a sensitive perception towards other disciplines.

I also wrote books covering topics like dynamic design, digital bionic and education. My last book, Creative Education and Dynamic Media is dedicated to teaching principles I developed during my time as visiting professor. However, I am not active in academia anymore. I personally left school rather early with the impression that the education system has huge deficits in nurturing creative thinking, individuality and self-responsibility.

Your latest project, the video for Bjork’s Tabula Rasa, has been inspired by the lyrics of the song and transcended into a personal animated interpretation. How did you envision this project in the early stages, and what was the process from beginning to end?

One of the strengths of Björk’s work is that it can be very personal and, at the same time, has universal relevance. We had many conversations about flowers and how they could be used to express growth, transformation and diversity. The main idea was to embody a constant state of metamorphosis, celebrating renewal. Thus, the visuals express certain aspects of the lyrics while still preserving space for interpretation.

Throughout your work, it is noticeable that the Chinese culture has had a great impact on your style. Not only through the themes of projects such as Kung Fu Motion Visualization, Virtual Actors in Chinese Opera or Xinjiang but through the overall aesthetic and type of movement, so evocative of the movement typology of Chinese arts. While you also operate from Hong Kong, could you detail a bit about the fascination you have for this culture and how it influences you?

Traditional Chinese culture is very holistic. Every discipline echoes other disciplines. For example, there are correlations between Kung Fu motions and stroke dynamics of calligraphy drawings. In Chinese Opera, actors are trained in singing and dancing likewise. To me, that is more appealing than the Western approach of separated specialisation.

I also have the impression that Chinese culture has a less egocentric concept of artistic authorship. The evolution of Chinese arts and craftsmanship favours sharing creative ideas and techniques rather than controlling their distribution. The fact that I, as a foreigner, could alter traditional elements of Chinese culture and those works are even appreciated and exhibited in many local museums shows a high degree of cultural openness.

Right now, I am working on a piece for a small performance festival, and a group of Islands called Steilene outside Oslo. I am fascinated with the processes that make a space into a place for us as humans. I am curious about what happens if creating connections to other species, and perhaps particularly red-listed species, is what informs this process for the audience members arriving at the island.

This work is almost like a little sketch, not lots of concept work, but just the process of doing it with audience participators. I often include guestbooks or other means of audience reflection in my work to catch some of the narratives that arise from it. I also try to work with other forms of documentation as an integral part of the work: video, stills and sound catching glimpses of experiences, narratives and processes as the work is running.

Some of your projects, such as the Tabula Rasa, are only in the digital medium. However, others, such as the one with the Chinese Theater and Media Scenography, implied merging the movement of real-life dancers with animation. What is the process behind this type of mixed project?

The video for Tabula Rasa was part of the stage visuals I created for Björk’s theatrical concert-show Cornucopia, which was projected on large curtains and screens during the show. In fact, most of my work is originally linked to a real event, be it theatre, concert or installation/exhibition. I enjoy this way of working because it often involves close collaboration and mutual inspiration among the participating disciplines.

Most of your projects deal with the idea of movement as a primordial and most important source of visualisation – generally, you seem to prefer to focus on the dynamism and its flow while keeping the whole “set design” neutral. How was this aesthetic born, and how do you envision it while operating from a static environment such as the digital one?

There is a lot of invisible information in movement, be it the motion of a human body or just clouds formed by the wind. It’s like looking at the tip of an iceberg while the profound forces operate below the surface. I am interested in unveiling these forces and rendering them into digital visuals beyond physical restrictions. This requires identifying core aspects, extracting and amplifying them and avoiding elements that are already sufficiently represented in reality. It’s like moving the subconscious into awareness by designing a cognitive shell for it.

Your projects, while abstract, do have a strong human component, the silhouette of a man being suggested or shown in various degrees. Through the delicacy of the images, these “creatures” tend to become endearing and personal and trigger the audience to emphasise them. Are they portraits of your personal postures or outside entities which you treat as a demiurge?

They are coming from the outside, often triggered by collaborations. I had little knowledge of Chinese Opera or Kung Fu before I have been commissioned to work with it. At the beginning of a project, I usually conduct a lot of research to get a deeper understanding of the topic. And during the creative process, I sometimes feel like a medium through which those topics turn into a new visual appearance. So it’s not about self-expression but empathy. In return, each project brings new insights. I’m constantly learning.

Where do you see your work going next?

It’s most likely that the collaboration with Björk continues a bit longer. Her work is an infinite source of inspiration. It is a great honour to collaborate with her.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

I personally don’t have an enemy that restricts my creativity. My brain constantly triggers ideas. It’s like a curse.

You couldn’t live without…

… nature.