Text by Charlotte Kent

Every March in New York City, the Armoury Art Fair isn’t necessarily known for its embrace of digital art, but as more artists use technology to express their visions, that is beginning to change. This year’s fair included an impressive roster of works addressing very different topics.

Tezi Gabunia’s 2018-20 BREAKING NEWS: The Flooding of the Louvre (Galerie Kornfeld) was evidently the most accessible work to an audience that is not necessarily interested in science or technology. The installation had crowds gaping at the wall projection of the Medici room in the Louvre as it filled with water. The artist reused the model of the room from earlier work to create the film, with the miniature room situated as people entered the curtained space. Implied in the title but not included was an evidence of the artist’s original post on Facebook Live.

The artist has done good work broaching issues of media, viral information, fake news, and the piece gains from that element. We’ve all seen the social media outpouring of concern for the demise of cultural artefacts, and then the inevitable waning interest. The issues of climate change are significant and well worth artists’ efforts to address, but that topic is well paired with the equally effusive anxieties surrounding information manipulation.

With all the fears around artificial intelligence, it was inevitable that at least one gallery would address the topic, but only one did and through the lens of early investigations. Crone Gallery’s AI Before AI showcased Joseph Beuys, Hanne Darboven, and David Link. The works are wildly different in content and approach but are an important reminder that a computer’s potential has been a part of the art conversation for longer than many in the larger art world recognize. Including Beuys is helpful because information and context are necessary to appreciate his highly conceptual works. Computer art arose around the same time and recognizing that it often needs a dialogue surrounding it is important for its wider dissemination.

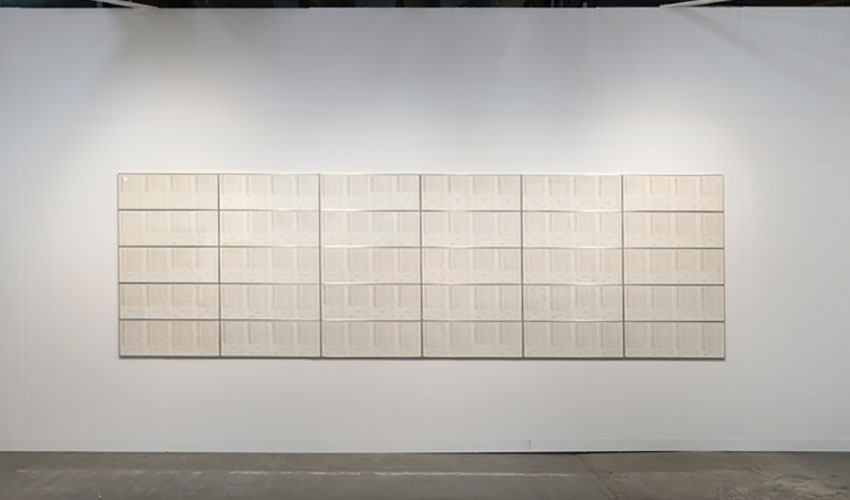

Amy Schissel’s installation and 4 large-scale paintings at Patrick Mikhail Gallery’s booth stand on their beauty, but understanding her interest in mapping contributes valuable depth to these works in traditional media. The paintings, done while in residency at the Joan Mitchell Foundation, seem like interstellar maps, with areas and information connecting across lines and shapes, patterns and designs. She pulls from the notational devices of a digital world to produce a sense of place for the analogue self. Without positioning us anywhere, as some artists working with maps aim to accomplish, she makes us place ourselves in relationship to it. Our use of digital maps may always tell us where we are but in a vacuum. The relationship of one object to the next, one person to the next, disappears unless we cultivate spaces for connection.

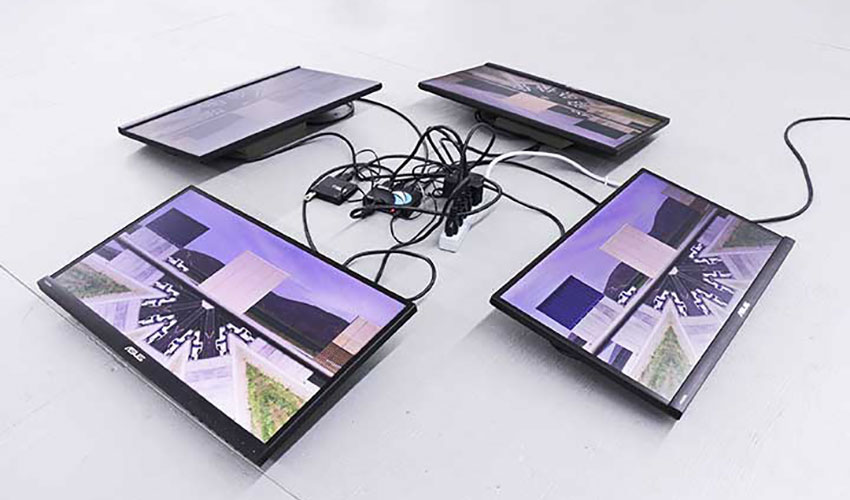

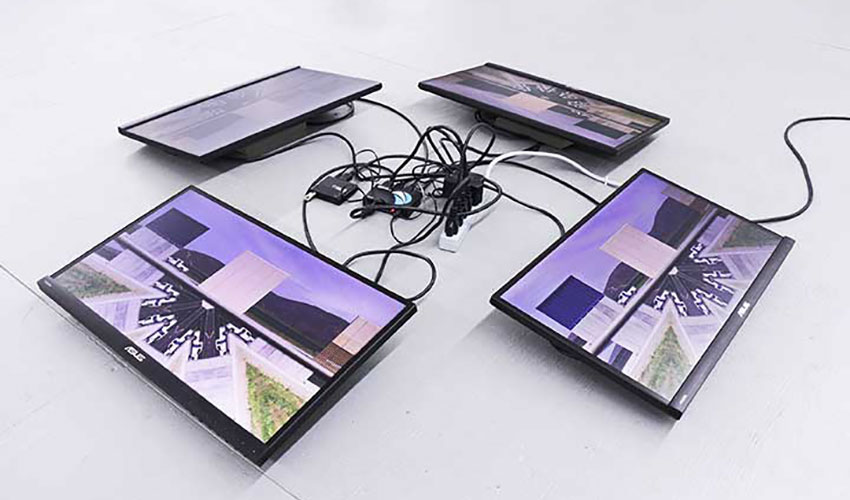

Peggy Ahwesh’s 4-channel installation Border Control at Microscope Gallery is unremitting in its criticism of current United States policies. The four flat screens on the floor create a square but the use of mirroring and kaleidoscope turn the walls and lines of the San Diego-Tijuana (United States-Mexico) border into disorienting circular space warps. Explanations were often necessary for audiences who peered into the screens but couldn’t discern what they were to see. Just as abstract art was once confounding, the visual complexities made possible by digital technologies clearly require articulation for an audience that is open to them, but uncertain how to commit to the viewing process.

This has been an issue for other forms of time-based media, and Ahwesh has used Super 8mm and 16mm film, heat-sensitive cameras, and drones, among other approaches, for her politically charged work since the 1970s. In the context of the current virus scares, the five separate works using touchscreens all provided gloves to help viewers reduce at least that level of fear about interacting with the works. This will likely become an expectation for all interactive works going forward.

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer is well known for his electronic art, and Max Estrella Gallery offered four distinct works. A screen of free-floating letters programmed using a dynamic equation flow into a sentence mid-screen, culled from the works of the 16th century Portuguese skeptic philosopher Francisco Sánchez text, Quod nihil scitur (That Nothing Is Known). It would take 2000 years to read the entire work at this rate but it allows the reader to pause with each thought. Slowing the reading process from the typical scanning to patient contemplation keeps readers hooked because as one sentence fades into the seeming distance, the swirl of letters flows into the next idea. The American author Don DeLillo writes his books with one sentence on each page because he believes he can communicate more precisely with such clear honing of language.

Lozano-Hemmer’s Recurrent Anaxagoras is a generative animation responding to NASA Solar Dynamics Observatory information. The work allows people to stare at the sun, but equally to consider our complex relationship with this fiery star whose position in relation to us has been a point of contention for scientific and ideological reasons stretching back into early language. We can’t look at it, but we need it, at this distance, but no closer nor far, and we can’t be certain of it, though we must presume it will be there rising every morning.

The Armory Show was once cutting-edge, but is now largely recognized as an established giant in the fair world. Its inclusion of galleries presenting (so-called) digital art or art engaging with science and technology indicates a steady welcome.

Works need to sell in order to really impact the art market, though attention from social media posts offers an engagement metric that is also relevant. The fast-paced temperament of a global art fair competes with the kind of attention these works require, in a culture that expects anything digital to be “user-friendly.” Whether collectors, individual or institutional, are prepared to commit to these works at an art fair will reveal to what degree we can continue to expect them there.