Interview Meritxell Rosell

Light as a medium, Space as a canvas with these words is how Joanie Lemercier defines his work. The French visual artist’s practice is primarily focused on projections of light in space and its influence on our perception. Lemercier was introduced to creating art on a computer at an early age by listening to classes on pattern design for fabrics taught by his mother, and patterns, geometry and minimalism have become a recurring and central part of his work.

Lemercier co-founded the visual label AntiVJ in 2008 with artists Yannick Jacquet, Romain Tardy and Olivier Ratsi, a group of European-based artists whose work focused on the use of projected light using various techniques such as video-mapping, tracking and stereoscopy to create holographic illusions. He worked on the stage design for festivals such as Mutek and worked alongside artists such as Flying Lotus and Portishead’s Adrian Utley and architectural projections all around the world.

In 2013, Lemercier founded a creative studio in NYC, focused on the research and development of artworks and experiments that use projected light in space, and since 2015, the studio is based in Brussels, Belgium, and ran alongside Juliette Bibasse. The work of Lemercier goes a step beyond the purely physical or material, playing with structures’ physics but also with concepts of philosophy to reveal how light can be used to manipulate perceived reality.

More recently, Lemercier has been turning to nature for inspiration, and in particular, the idea of the German sublime and some beliefs and theories from Dutch philosopher Spinoza, such as Pantheism. This topic is explored in the audiovisual project of the same name, which premiered at the LEV festival in Gijon in 2016. In it, projections are formed by straight lines and repetitive, simple patterns representing a structure of landscapes, rocks, planets and caves, heavily inspired by Sol Lewitt’s mural paintings.

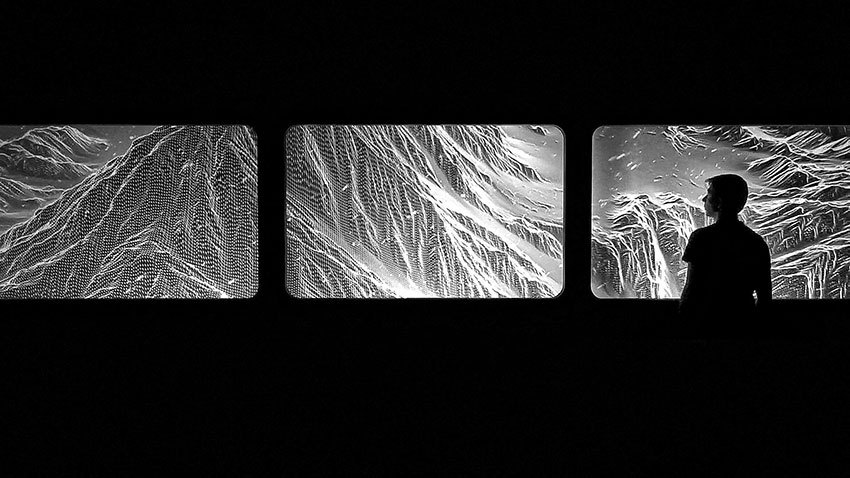

In Nebulae (2019), an audiovisual piece designed for domes and commissioned by Sonar+D, the studio developed a touching exploration of galaxies, constellations and mesmerising cosmic events and follows up other projects researching into themes of space and cosmos such as Cosmos express (2017) and Nimbes (2014), this last one in collaboration of James Ginzburg of Emptyset). In Brume (2017) and Constellations (2018), the studio explores the use of water for projections.

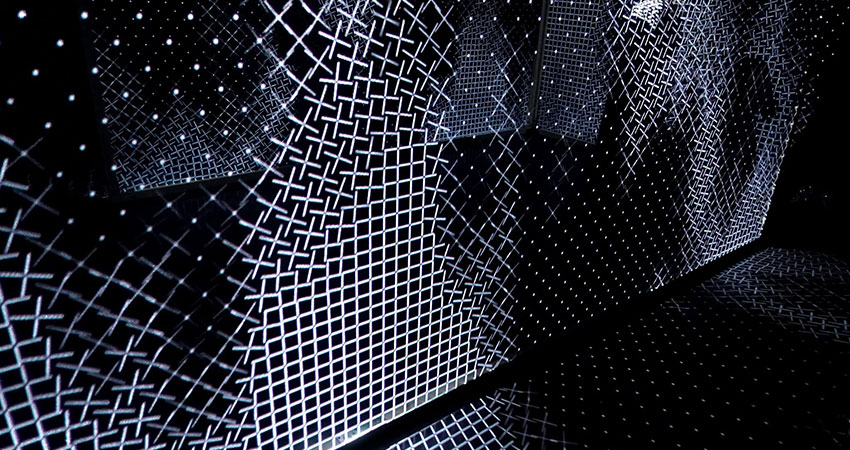

Constellations is an audiovisual installation where light is projected onto invisible water particles to form shapes and intangible structures in the air: an abstract journey through geometric structures formed by the universe. On the other hand, in Motif Wallpaper (2018), intricate patterns and geometric structures are revealed in all their magnificence. The projections enhance the sense of depth and distance and question the nature of reality, while the interactive part allows the visitor to control and manipulate the projection.

The work of Lemercier presents unique light performances and installations that challenge the audience by creating optical illusions that question one’s perception of space. Taking visuals away from the restrictions of flat rectangular screens, we see how he transforms flat surfaces, sculptures and buildings into hypnotising canvasses to create immersive site-specific experiences.

Lemercier makes projections that transform building facades, domes and installation spaces with minimal geometric patterns working alongside all sorts of collaborators, from scientists and architects to 3D artists and musicians (including Jay Z), to add dimension to his work. The symbiosis of live tracks and Lemercier’s visual performance sparks a kind of pure emotional reaction, feeling like floating through an interstellar nebula, and another that turns the space into a massive refracting kaleidoscope.

Right: Nebulae (2019)

Your work is infused with patterns, geometry, and nature; Where does the inspiration come from?

It comes from a personal story. My mother was an art teacher, and she also taught graphic design at a fashion school. The students used the computer to draw patterns for fabric. They designed patterns on the screen that were printed on paper or fabric to make clothes. My school was very close to where she was teaching, so I had only to cross the street to join her at the school twice a week, where I could use a computer. There’s a deep connection between how I started using a computer and what I do now; my love for patterns comes from this background.

More recently, I’ve been exploring nature, especially mountains and volcanoes. I think this is a completely different topic, probably unrelated. It’s like two things I do in parallel. I think I was surrounded by technology and computers too much for the past 10 years, as I was always working with a laptop and computers; in order to find some sort of balance, I started doing hikes and then became really excited about nature as the subject of my work.

As a result, I discovered the art current called the sublime, which included 19th-century romantic painters such as Caspar David Friedrich and William Turner. I realise now that even if I use technology and a computer, what I’m obsessed with is probably the same idea of the sublime, looking at a landscape that is so vast that it’s beyond our comprehension. That’s the second subject I’m, I’m really, really excited about these days. It’s the ‘sublime’ in nature.

Do you find similar patterns in things that you find in nature and things that you generate by mathematical models or computers??

Right now, my field of research is how I can use generative code and generative design to simulate things like mountains, clouds or the ocean. These are not motifs or patterns strictly, as I see the definition of patterns. A mountain, cloud or ocean it’s not something you can predict so easily because if you see a bit of water or a picture of the ocean, you can’t tell what the next wave is going to look like.

So it’s not a repetitive pattern in the sense that it’s mathematically linear, but still, I’m really interested and excited by the relationship between algorithms and these shapes. Maybe they’re not patterns, but there are structures that you can find in nature, and actually, it’s easy to simulate them in the software. You can use values and techniques.

There are a lot of techniques used in video games that I use a lot. The idea is to use a noise function. So it’s actually a matter of simple mathematical function. And with this noise, with this texture, you can recreate a cloud, the mountain, the surface of the ocean, and it’s not a repetitive necessity. It’s very sort of organic and a little bit complex.

Does this modelling require inputting lots of variables?

Not necessarily. Of the simple functions, there’s one called burning noise, which was actually invented by an American guy working in VFX in the film industry. I think he worked on Tron in 1982. And then, he worked extensively in the video games industry. His noise function is actually very simple; it’s just a single line.

Even if you don’t have a degree in mathematics, with a single function, you can create a very, really wide variety of realistic landscapes. And I think I’m quite obsessed with this idea that maybe there’s a function in the universe that you can use to recreate everything.

Which is very beautiful, from a mathematical point of view, being able to find the perfect equation to describe everything. But at the same time, I almost hope this kind of function doesn’t exist because if you can predict everything in the present, past and future, it would make everything way less exciting.

Your work explores light and space and their influence on our perception; what do you want to achieve with your work; is it to make the audience question their perception of reality, or is it more a personal exploration?

I don’t really project myself into what the audience could say. I guess I try to use these tools to have something that in front of me would challenge reality. What’s really easy with human beings is that, although the light is a strong medium and we all perceive light in a sort of similar way, there are slight differences. But for a regular audience, you can expect that they will see the same thing as I will; there’s no language barrier, and therefore light can act as a universal language.

And what actually made you decide to work with light?

As I mentioned before, apart from the two subjects that I like exploring, nature and geometry, the third one is the use of light. This was almost by accident when I started using video projection as a medium around 12 years ago; I started doing projection mapping onto buildings and projections in clubs.

A few years later, I realised that I could do projections so precisely that I could change how scenes looked like; I could project on a piece of paper the texture of wood. So it would look like a piece of wood and not paper anymore. Meaning you can actually sort of change or modify reality a little bit. After exploring these ideas for years, I now realise what I like is the idea of creating an illusion or maybe altering perception, when you can question the very nature of reality.

You have recently been using water in your project Constellations; what does this media bring about to your pieces?

Throughout my career, I’ve always tried to get away from the screen. To remove the physical screen we have so many screens in our daily lives; think of phones, computers, TV and so on. The interaction between images and content is constrained by the screen. So I like using light, but I don’t want to be stuck in a rectangular image.

I have spent the past 10 years trying to get away from this rectangle. I tried a variety of materials like transparent fabric or reflections on mirrors, and water is a very convenient medium to work with because you can make the water particles so thin that they become almost invisible, but at the same time, they can be a perfect canvas for light and projection.

Water allows me to create a sort of intangible structure. I’ve tried different techniques, and now I use the different states of water. When I use atomised water, I need high pressure to break each of the drops into very tiny invisible ones. Now I can create a projection without the need of the physical screen that you touch. Actually, the water is sprayed into the air.

You’ve also done some collaborations with scientists (nanolab residency). Do you work with scientists regularly, or would it be something you’d like to explore further? How was the experience?

There are a lot of things I want to explore that I actually need some knowledge that I don’t have. It’s not always easy to find these opportunities because the economy around science labs or science companies doesn’t often intersect with the art world except when an institution decides to make a connection. In the case of Gnration residency in Braga in, Portugal, they decided to open their doors to have artists’ insight, which is still a very rare kind of context.

Once the opportunities occur, the interactions sometimes are not so easy because scientists and artists have very different languages, and it can take a bit of time to communicate ideas. At a personal level, my background in science is not so great, and some of the concepts are very far in my memory; it can take a lot of effort to work with a different language and time frames used by scientists

How did you find these interactions with scientists?

It’s super interesting because it allows everyone to sort of focus on collaborating and trying to find a bridge between these worlds. I also like the fact that it’s usually for a short amount of time. I don’t think I’ll be able to do a project in a science lab for more than two or three weeks, but it’s always nice when there’s an opportunity.

So I hope I can keep doing this maybe once or twice a year in different fields because I really want to have a better anchor into reality. Like for example, with the Gaia mission, I have access to the data from the European Space Agency (ESA). So I’m now trying to have a bit more sort of grounded reality in my pieces as opposed to just making a beautiful-looking image.

You also have been trying to project without a screen or a surface with the hologram projects; what are the biggest challenges you have faced?

With light, you can actually modify reality in a sense that if you extrapolate, these experiments allow me to create a sense of depth. I’m trying to push this illusion and to be so realistic that it feels like you can project in 3D in space. It’s just an illusion, a projection onto a flat material, a flat invisible screen.

And then I do a head-tracking so I know where the viewer is, and I change the perspective of the projection, so it’s just an illusion trick. But when you look at it, you wonder if it’s real or not, that is why I like this idea of questioning reality and its nature.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

The capitalist structure. There are a lot of ripoffs or copies of existing work. This is capitalism, this idea that with money, you can actually own everything.

You couldn’t live without…

If I was blind, I would be really, really, really sad because a lot of my work and my life revolve around the use of light. And, of course, nature probably comes first, but light is part of nature itself. So I would say maybe just nature.