Interview Allan Gardner

Huma is the alias of Barcelona-based experimental musician Andrés Satué. His latest release, titled Emergence (Hedonic Reversal, 2021), is an experiment in the irregular rhythmic, textural or physical qualities of sounds engaging with one another. The chaotic nature of these sounds colliding allows for the emergence of atypical rhythms in which preconceived notions of a linear structure are supplanted in favour of melodies and patterns borne from the dissonant sound.

Inspired by emergence theory, the state of being where a collection of parts form an entity with properties not held by the individual parts alone, this new release is an exercise is finding musicality in abstract sound. Like sonic sculptures brought to life, the samples and textures created have an isolated sense of being – actors in a play; they combine to form the composition’s narrative. Addressed as a story told in abstracts, Emergence avoids many direct references to sonic contemporaries in favour of adopting its own diverse, attuned uncanny, sonic palette.

Finding a word to describe the sounds in Huma’s work is very challenging. Existing somewhere between a digital synthesis of physical sounds and a heavily manipulated field recording, it’s difficult to place what you’re hearing on first listens.

This decision is an effective one; embracing the physicality of the sound allows it to be considered for its communicative property, something malleable that can be stretched and contorted, hidden or emphasised over the course of the track. For the new record, listening to the release with emergence theory in mind, we are encouraged to consider the sounds as individuals before we address them as part of a composition, adding to the sense of motion, the idea that the times when the record becomes most musical are somehow random, or naturally occurring.

Something that I find particularly interesting in Huma’s work is the different approaches to interpretation that the different contexts give the productions. It separates the listener from a traditional listening experience – to think about whether we like these sounds, whether this music is appealing to us, is not a pressing matter in regard to this.

The personification of the individual sounds makes it seem more like we are being given singular propositions in the context of a wider dialogue – like sitting at a pitch meeting. Dissonant sounds push up against more soothing ones; we’re made aware of the potential future absence of this balance, the evolving composition evoking a sense of apprehension or anticipation.

With Emergence, maybe it is most interesting to consider it as point A, with the listener’s interpretation as point B. The compositions we hear on the record are often unrelated or clashing sounds, individual players interacting with one another. The composition emerges from this interaction, and as we hear it, we break it down again into its parts. A separate emergence happens, whereby the electrical impulses in our brain tell our bodies how to react, and our interpretation is formed from this. Our consciousness, our ability to pull apart the theory or the music it inspired, is entwined in it before we begin.

Your work, you mention, is generally driven by narratives. What types of narratives are you most interested in? What use do you make of your equipment to aid you in the creation of these narratives?

Any original or appealing idea, usually relative to science or philosophy but not always, basic human questions trying to be answered by new ideas that I find interesting.

In the past, I didn’t make a setup according to the narratives; the narratives were a limitation for the music itself, but not for the gear. This album is different, yet the ideas that inspire me have nothing to do with the equipment but with the music and creative process.

Your sound also feels very physical, is the physicality of the sound something you are interested in? What are your live sets like?

Yes, I’m very interested in physicality; it is written in my tech rider. I like to think that my music is created to be played live, and that’s where it all makes sense, so I make a big effort to translate the album into live, trying to instil some kind of narrative based on the music and the concept. Also, the listening environment is completely different from album to live, so the music and staging should take that into account.

My live set depends on the music or album we are performing, but I can say that it will always have narrative, intensity and abrasion. For my following set, I will be working the visual part with Mitrilo Collective (Razorade, Sevi Ico Dømochevsky…), which made the video for Coherence. So you can count on impressive visuals, fog and strobes.

You have just published a new album, Emergence, where you mentioned changing your creative process from more narrative-focused to gravitating more towards sensations. What were your intentions for the album with this change?

It’s a long process. I almost always have some idea running around in my head that haunts me and that I try to express in some way in the album. On the other hand, these ideas help me set the boundaries and direction of the music and the creative process.

In the beginning, it’s a bit chaotic. I spend a lot of time testing and researching the sounds that will later form the album’s colour palette. In this case, besides a sound, I was looking for a process, a chain of midi and audio effects with which, by applying variations, I could get different results that would finally compose the different tracks of the album. I think of it like I used to design the album itself, the music. But now, I try to design a process by which the music will be created.

And what was the intellectual process behind the inception of the album? And what challenges you faced in its production?

This change in the way I approach the creative process has had a result that I didn’t expect or think about. Still, finally, it’s quite evident: it is the album more direct and intuitive that I’ve done so far; it’s kind of liberation not having to think and decide about every sample, sound, etc. and play with the set of tools and effects that give rise to the sounds, rhythms, structures and melodies that in the end make up each part or track of the album.

You mention that conceptual aspects still drive your practice, and for this one, you worked with the theory of emergence, a concept that goes as far back as to Aristoteles. What about this theory that attracts you, and how have you incorporated it into the album?

Yes, the theory of emergence is a very old idea, but it was not until the 19th century that it began to be developed. It basically says that from the interaction of a large number of simple particles of which we know their properties and behaviour, more complex properties can emerge that are impossible to predict. That is, the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. The strange thing is to see how this happens everywhere: the ants when they work as a team, the birds that fly in flocks and seem to move as if they were a single consciousness, the formation of complex symmetrical and fractal patterns in snowflakes, the famous game of life of Conway, also consciousness could be expressed as an emergent property of the interaction of neurons in our brain, and even recently several scientific theories are based on this idea to try to approach the theory of everything. So this seems to be almost everywhere.

That is why it is one of the most attractive ideas I have ever come across, and it seemed interesting to try to bring it to the creative process. To do this, the idea was simply to create a set of input parameters and make the output to be something that emerges from the interaction of the tools and effects that take part in that process.

Applied to music, the emergence theory reminds me of building modular systems. What have you technically been exploring in the album?

Yes, it can resemble modular. Technically I used a similar approach to what can be achieved with modular synthesis, but with software. Nowadays, software is very capable of emulating anything, and not only that, but creating new ways of processing sound that maybe even using modular synthesisers are not possible. I’m very interested in physical modelling and granular synthesis. Using the first one, you can get almost real sounds emulating materials like metal, crystal, wood, and shapes like string, plate, tube, etc. This is really appealing to me; by starting to process a sound that resembles a real thing, you can then move on to play on the line that separates what sounds real or unreal.

Could you tell us more about the visual aspect of the release?

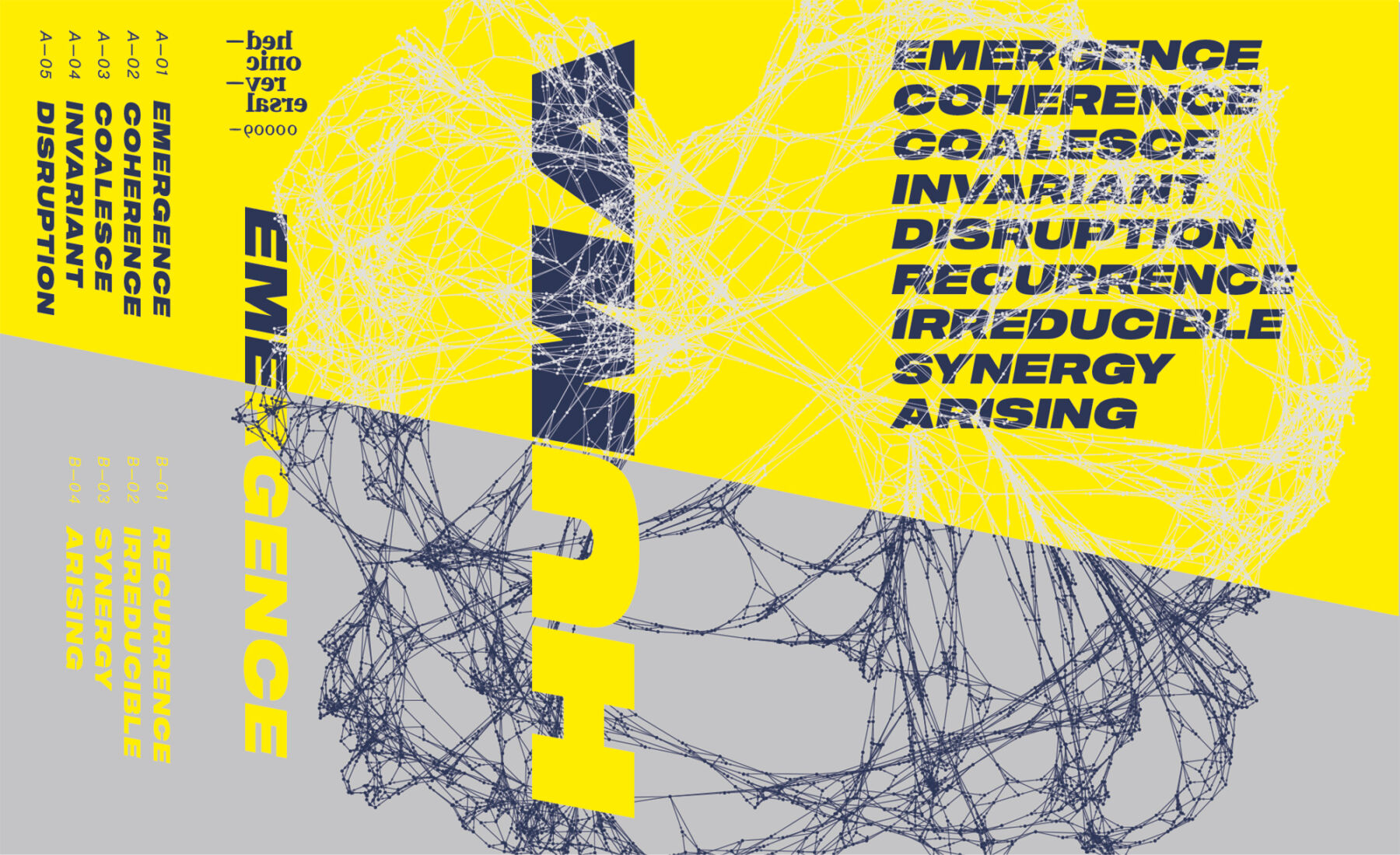

The design has several layers. The art direction was done by my label mate, Miguel Sueiro, who creates great designs for all the label’s releases. This time for the main artwork and slipcase, he used a still from the awesome video that Razorade and Sevi Ico Domochevsky made, but for the cassette insert, we used a hypergraph from the Wolfram Project, a hypergraph is a graph in which generalized edges may connect more than two nodes, in other words, an image that represents the relationships between the abstract elements of a system.

The Wolfram Physics Project, according to their own words, “is a bold effort to find the fundamental theory of physics. It combines new ideas with the latest research in physics, mathematics and computation in the push to achieve this ultimate goal of science.” Where the theory of emergence plays a very important role, so it was a perfect fit with the concept and the artistic direction.

Solitude or loneliness; how do you like to spend time on your own?

A nice album, a mix, a book or a documentary, maybe with a glass of wine… This or being immersed in the studio trying out new music ideas.

You couldn’t live without…

Other people.